by Rakashi Chand, Reading Room Supervisor

In the aftermath of Valentine’s Day during the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution, we invite you to celebrate some of the most romantic figures of the Revolutionary era.

The Couple

In the turbulent years when a young America was struggling to define itself, two young people met in a bookstore. Her name was Lucy Flucker, just sixteen, the daughter of a wealthy Loyalist family whose father ranked as the third highest British official in Massachusetts. His name was Henry Knox, a Boston bookseller who devoured volumes, was outgoing, warm, endlessly curious, and remarkably intelligent.

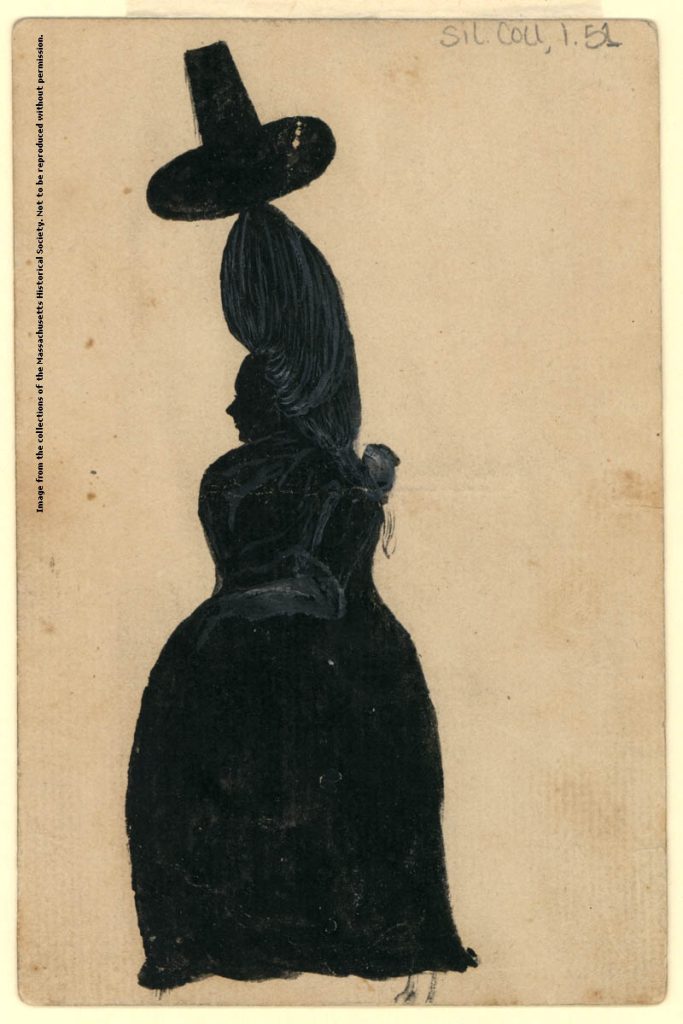

By every measure of class, politics, and expectation, she was not meant to fall in love with Henry Knox. Yet she did, and with the courage that would come to mirror the revolution reshaping the world around them. This silhouette at the Massachusetts Historical Society is the only known contemporary image of Lucy Flucker Knox.

The Marriage

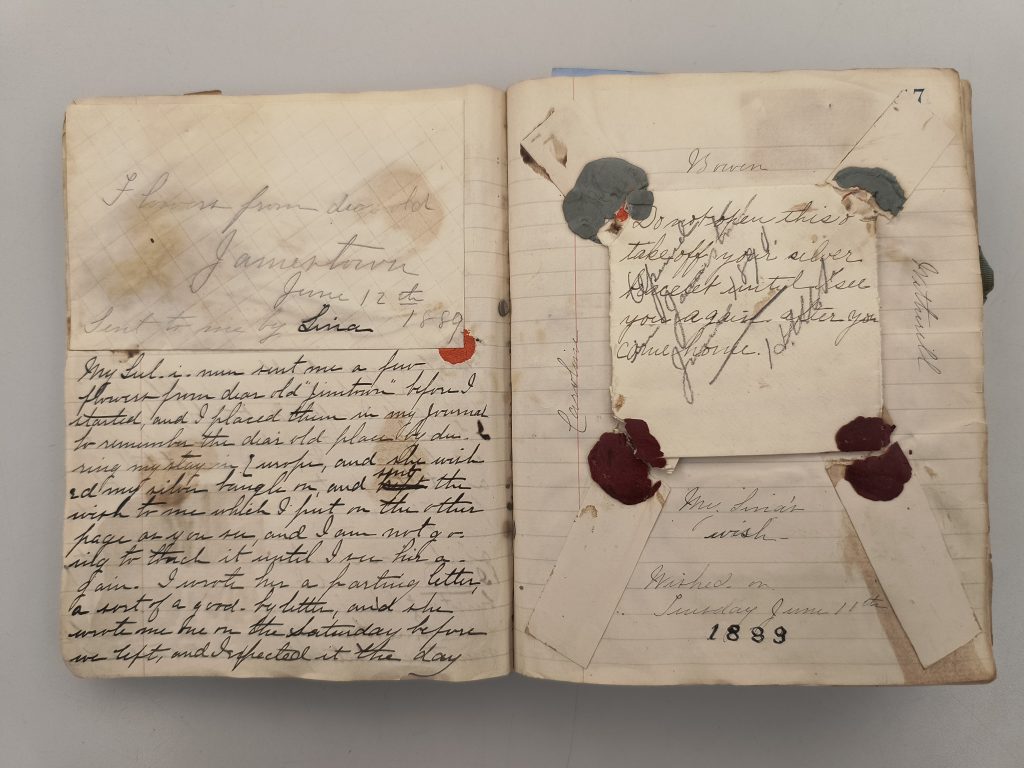

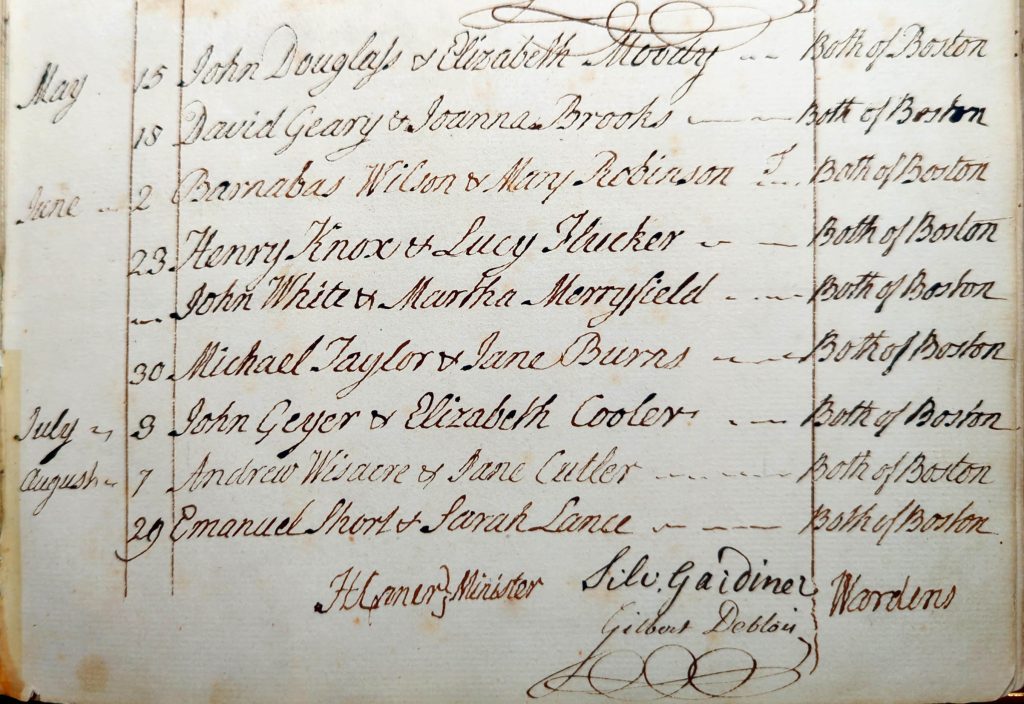

Their affection grew in the corners of a city on the brink of war and soon they married, defying her family and the life laid out for her. Although Lucy and Henry are well documented and significant figures in the formation of our nation, for a while there was considerable confusion about where and even when they were married.

For a deeper look at the confusion surrounding their wedding, read these two posts from J. L. Bell’s Boston1775 blog: “When did Henry Knox and Luck Flucker marry?” and “Where did Lucy Flucker and Henry Knox marry?” Bell notes that the couple married at King’s Chapel in Boston. Luckily, the MHS houses the Records of King’s Chapel, and a dive into the archives shows the recording of their marriage on June 23, 1774. Lucy’s sister Hannah and half sister Sallie attended the wedding, but her parents were notably absent.

The War Begins

A year later the Battles of Lexington and Concord forced the young couple to slip out of Boston for their safety. Lucy took refuge in Worcester, Mass., never to see her family again, while Henry joined the militia besieging the city. He directed fortifications using knowledge he had gained from his books, and in his first surviving letter to Lucy, dated July 6, 1775, he described meeting George Washington, who was impressed by his engineering skill.

Not long after, Henry embarked on his now famous feat, transporting 59 captured cannons from Fort Ticonderoga over 300 winter miles by ox drawn sled to Boston. Washington positioned the guns above Boston and forced the British to evacuate. Henry, only twenty-five, became commander of the Continental Army’s artillery and would rise to major general before the war’s end.

As the American Revolution ignited, the nation and the newlyweds came of age together. Forced apart by battle lines and duty, Henry and Lucy kept their bond alive through letters that pulsed with longing, fear, devotion, and hope. With Henry often away, Lucy also grew into a woman forged by independence and responsibility, writing him on 23 August 1777 that “I hope you will not consider yourself as commander in chief of your own house.”

The Love Letters

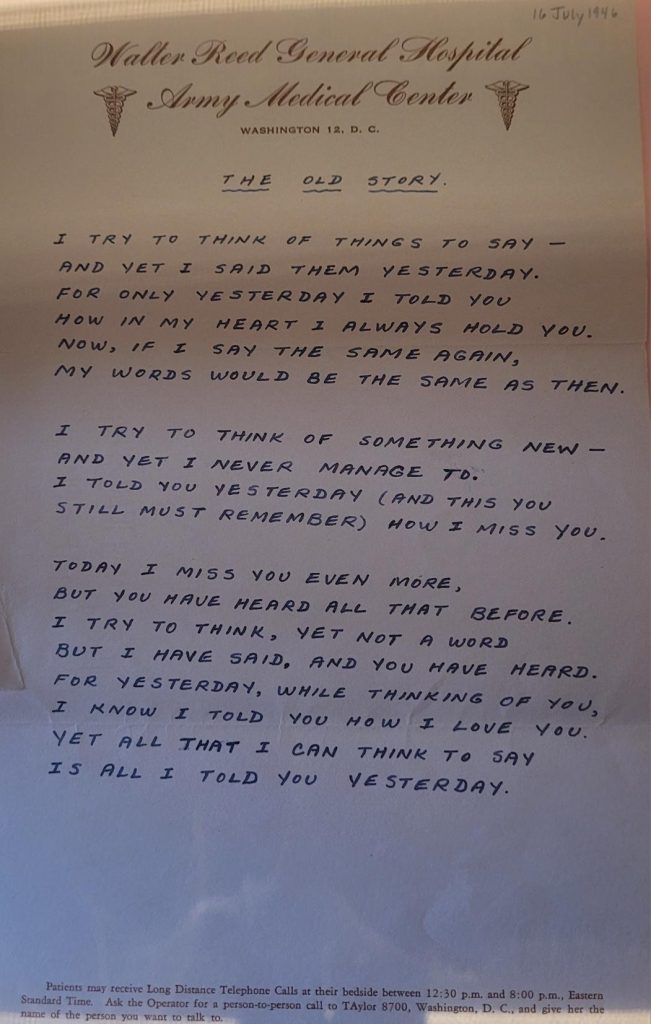

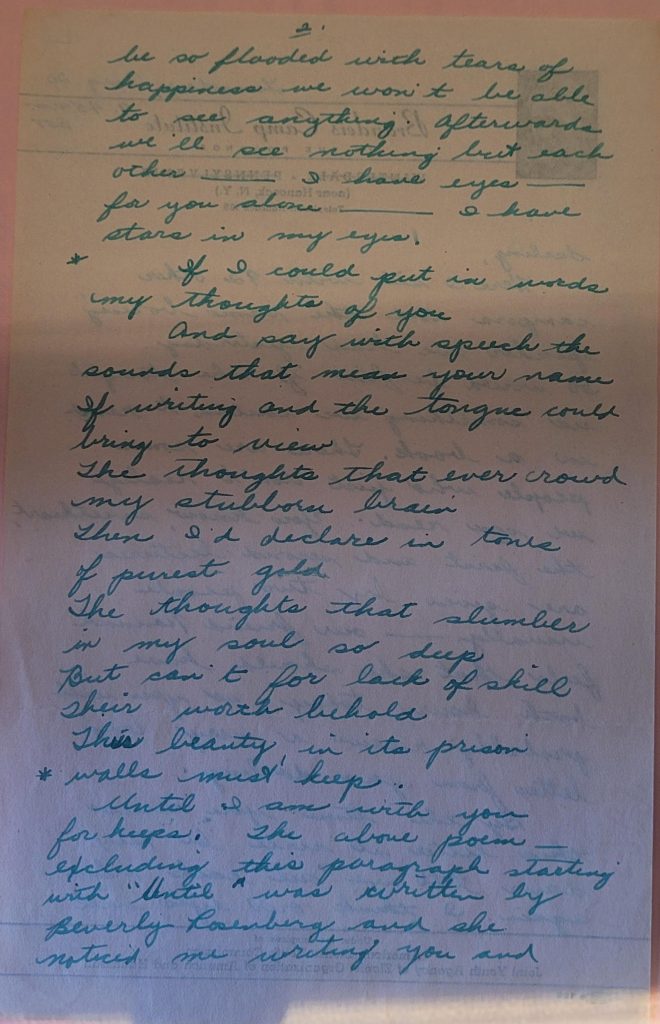

The wartime correspondence between Henry and Lucy Knox offers a vivid, intimate window into both the American Revolution and the emotional world of a couple separated by conflict. Over the course of the Revolution, they exchanged more than 150 letters.

Below are a few excerpts that illustrate the tone and content of their letters to one another, demonstrating their commitment to each other during a remarkable time.

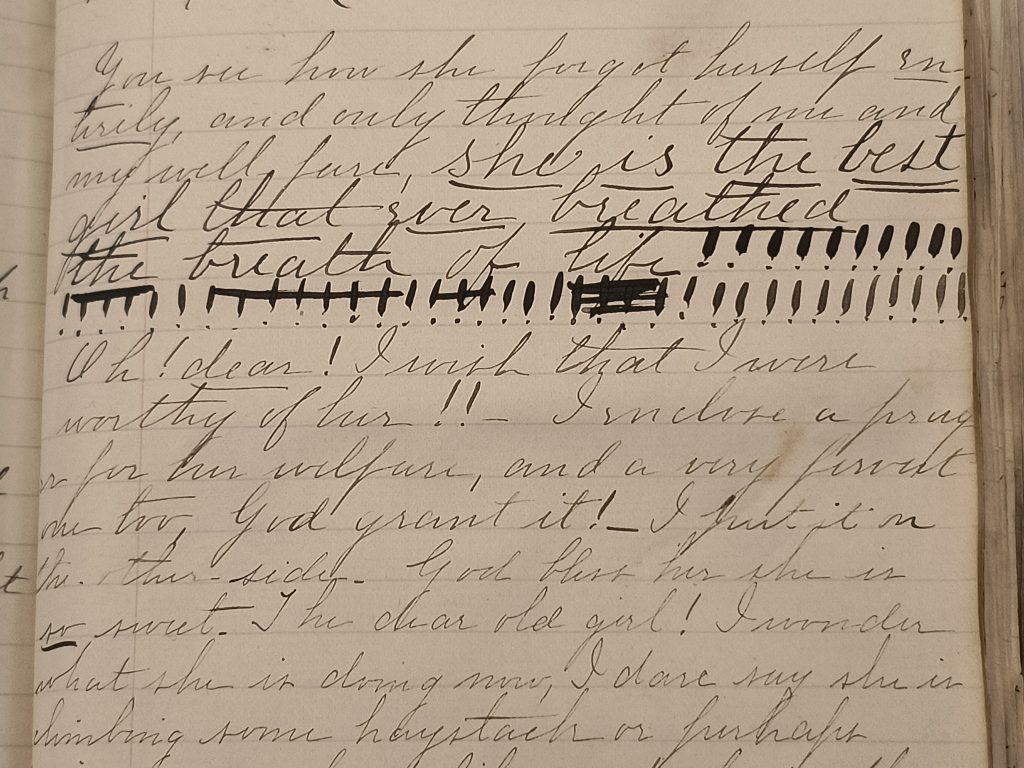

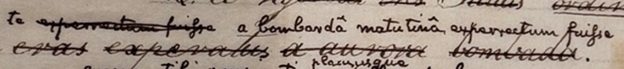

This rich letter from Henry notes both the sadness of separation and the hardships encountered in transporting the artillery from Fort Ticonderoga, though is not without humor.

“My dearest Companion, It is now twelve days since I’ve had the least opportunity of writing to her who I value more than life itself. . . .Had I the power to transport myself to you, how eagerly rapid would be my flight. It makes me smile to think how I should look, like a tennis ball bow’ld down.”

Henry Knox to Lucy Flucker Knox, Ft. George, NY, 17 December 1775

Their letters continue to gush with love and sadness at separation.

“My lovely & dearest friend, Those people who love, as you & I do, never ought to part. It is with the greatest anxiety that I am forc’d to date my letter at this distance from my love at a time too when I thought to have been happily in [your] Arms.”

Henry Knox to Lucy Flucker Knox, Albany, NY, 5 January 1776

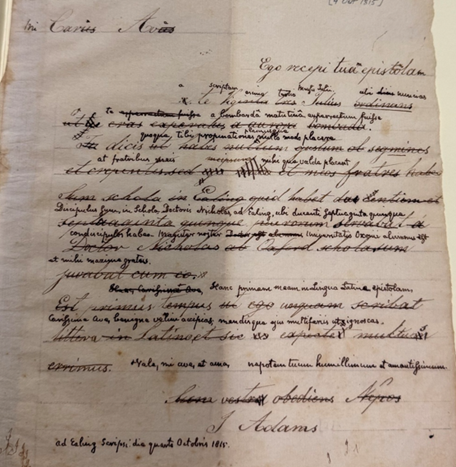

“I should long before this have indulged myself in the pleasure of writing to him who is allways in my thoughts, whose image is deeply imprinted on my heart and whom I love too much for my peace, but the fear that the language of a tender wife might appear ridiculous to an impartial reader (should it miscarry) has restrain’d me.

Lucy Flucker Knox to Henry Knox, Boston, MA, 29 or 30 April, 1776

Born in a bookstore, tested by war, and carried in ink, Henry and Lucy’s love came of age alongside a nation fighting to define itself.

Further Reading:

The Henry Knox Papers, on microform at the MHS, owned by the Gilder Lehrman Institute, include the correspondence between Henry and Lucy Knox

Henry Knox Papers II collection

Henry Knox Papers III collection

Hamilton, Phillip. The Revolutionary War Lives and Letters of Lucy and Henry Knox. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017.

Stuart, Nancy Rubin. Defiant Brides: The Untold Story of Two Revolutionary Era Women and the Radical Men They Married. Boston: Beacon Press, 2013.