By Susan Martin, Collection Services

Boylston Street, the address of the MHS, is named for Boston philanthropist Ward Nicholas Boylston (1749-1828). No full-length biography of Boylston has been written, but what we know about his life is intriguing. He was born Ward Nicholas Hallowell and changed his surname in 1770 as a condition of his inheritance from his uncle. Although he was a Loyalist during the American Revolution and lived in London between 1775 and 1800, his first wife was the daughter of an American revolutionary, and his second cousin was President John Adams. He was estranged from his oldest son Nicholas (for unknown reasons) and bequeathed him a small annuity in his will…as long as Nicholas never returned to live in Massachusetts.

Now, staff here at the MHS have come across another Boylston family plot twist.

One of the editors on the Adams Papers Editorial Project recently found what seemed to be an error in a footnote: the birth dates of Ward Nicholas Boylston’s two younger sons. Records indicate that Thomas and John Lane Boylston were born in 1785 and 1789, respectively. However, Boylston’s first wife Ann died in 1779, and he didn’t re-marry until 1807. So who was the mother of Thomas and John?

The most likely explanation was that one of the dates was wrong. But a careful look through the MHS collection of Boylston family papers confirmed that Ann (Molineux) Boylston died in 1779 on a voyage to America, and that Ward married Alicia Darrow, or Darrham, at Boston’s Trinity Church in 1807. Had he been married in London during the intervening years? If so, we have no record of it.

One letter in the collection suggests an answer to the mystery. The letter was written by Robert Bentham, the uncle of Boylston’s grandson Henry, on 23 Mar. 1840. It relates to Henry’s inheritance.

My nephew claims an Interest in this property as the only surviving Son of Nicholas Boylston (now deceased) the eldest Son (indeed the only lawful Son) of Ward Nicholas Boylston…. I pass over the doubt which exists & has for many years existed, as to the marriage of the present Mrs. [Alicia] Boylston (the styled widow of Ward Nicholas Boylston) or the legitimacy of her children. When I first became personally acquainted with the family she went by the name of Davis. All her elder children went by the name of Davis…. The fact was notorious in the neighborhood.

On this statement various & important questions must of course arise, which I shall not be so indelicate to propose, & far less to obtrude an observation on, or answer thereto….

His implication is clear. Assuming that Thomas and John were Alicia’s sons, they were born before she was Boylston’s lawful wife. It’s possible that Alicia had been previously married, to a Mr. Davis, but Bentham had no knowledge of it.

The historical record is often fragmentary and misleading, and we may never know the truth behind Bentham’s claims. Unfortunately, the Boylston collection contains very little personal correspondence between the family members directly involved. A thorough search through the papers of Boylston’s contemporaries might shed some light on the subject. I’m told Louisa Catherine Adams had an appetite for gossip. Maybe one of our intrepid researchers will take up the challenge…?

Marian Hooper Adams was nicknamed “Clover” by her mother, who felt that her daughter’s birth was a lucky occurrence. Born into a wealthy, prominent Boston family, Clover was raised in privilege and highly educated. Her mother died when she was five, but Clover remained very close to her father for the rest of her life. In 1872, at the age of 28, she married the historian Henry Adams, who was teaching at Harvard. After five years they moved to Washington, DC, residing near the White House, and began hosting an exclusive salon of politicians, writers, and thinkers. Despite this stimulation, Clover and Henry were bored, and the spark went out of their marriage. Their problems intensified due to the fact that they were unable to have children.

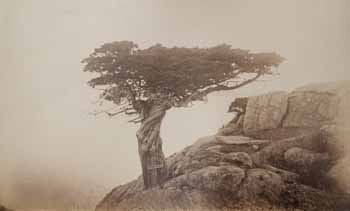

Marian Hooper Adams was nicknamed “Clover” by her mother, who felt that her daughter’s birth was a lucky occurrence. Born into a wealthy, prominent Boston family, Clover was raised in privilege and highly educated. Her mother died when she was five, but Clover remained very close to her father for the rest of her life. In 1872, at the age of 28, she married the historian Henry Adams, who was teaching at Harvard. After five years they moved to Washington, DC, residing near the White House, and began hosting an exclusive salon of politicians, writers, and thinkers. Despite this stimulation, Clover and Henry were bored, and the spark went out of their marriage. Their problems intensified due to the fact that they were unable to have children. Clover had always been interested in art and she found an outlet for her frustrations in a new camera in 1883. She learned the painstaking development process and began to take photographs of people, landscapes, and animals (she was a great lover of dogs and horses). Although a few of her photographs show traces of humor, including those of her dogs posed at a table set for tea, many of Clover’s photographs convey the melancholy and isolation of her own experience.

Clover had always been interested in art and she found an outlet for her frustrations in a new camera in 1883. She learned the painstaking development process and began to take photographs of people, landscapes, and animals (she was a great lover of dogs and horses). Although a few of her photographs show traces of humor, including those of her dogs posed at a table set for tea, many of Clover’s photographs convey the melancholy and isolation of her own experience.

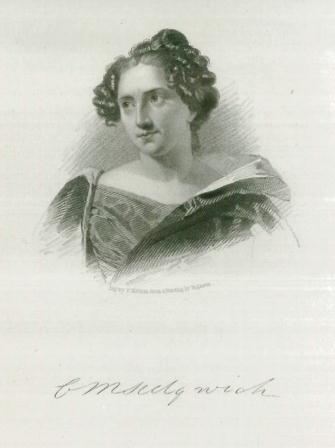

Catharine Maria Sedgwick (1789-1867) was a member of the illustrious Sedgwick family of western Massachusetts and a prolific antebellum author. She wrote many novels and short stories between 1822 and 1862, including A New-England Tale, Redwood, Hope Leslie, Clarence, The Linwoods, and Married or Single? Very popular in her time and praised by many of her contemporaries, including William Cullen Bryant, James Fenimore Cooper, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Harriet Martineau, and Edgar Allan Poe, Sedgwick was largely overlooked by scholars in the century following her death, and most of her books were out of print for decades. Recently, however, there has been a resurgence of interest in her life and work.

Catharine Maria Sedgwick (1789-1867) was a member of the illustrious Sedgwick family of western Massachusetts and a prolific antebellum author. She wrote many novels and short stories between 1822 and 1862, including A New-England Tale, Redwood, Hope Leslie, Clarence, The Linwoods, and Married or Single? Very popular in her time and praised by many of her contemporaries, including William Cullen Bryant, James Fenimore Cooper, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Harriet Martineau, and Edgar Allan Poe, Sedgwick was largely overlooked by scholars in the century following her death, and most of her books were out of print for decades. Recently, however, there has been a resurgence of interest in her life and work.