By Jolivette Shevitz, Library Resident

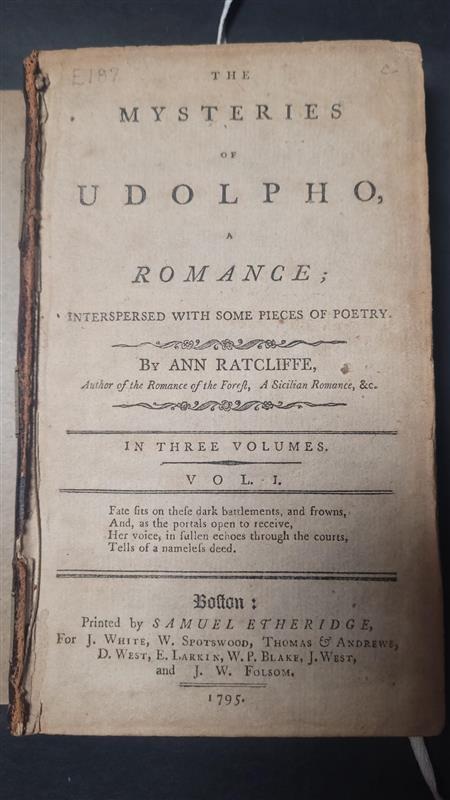

I was first introduced to author Ann Radcliffe through rare book collector Rebecca Romney’s book Jane Austen’s Bookshelf. Ann Radcliffe (1764-1823) pioneered the genre of Gothic Romance and her books awed and influenced both Rebecca Romney and Jane Austen. In the Massachusetts Historical Society’s catalog, ABIGAIL, I discovered that the MHS owns a 1795 Massachusetts printing of The Mysteries of Udolpho, Radcliffe’s most famous novel, which was originally published in England in 1794. I decided to read the three-volume set and experience the book just as someone would have in the 1790s when the book was originally published.

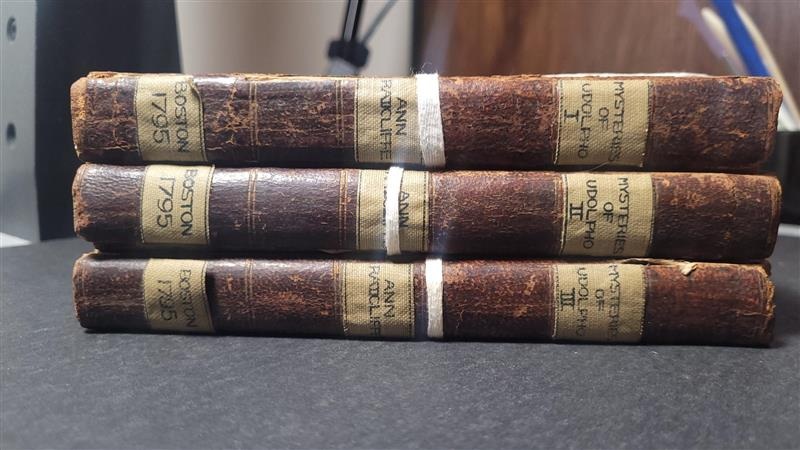

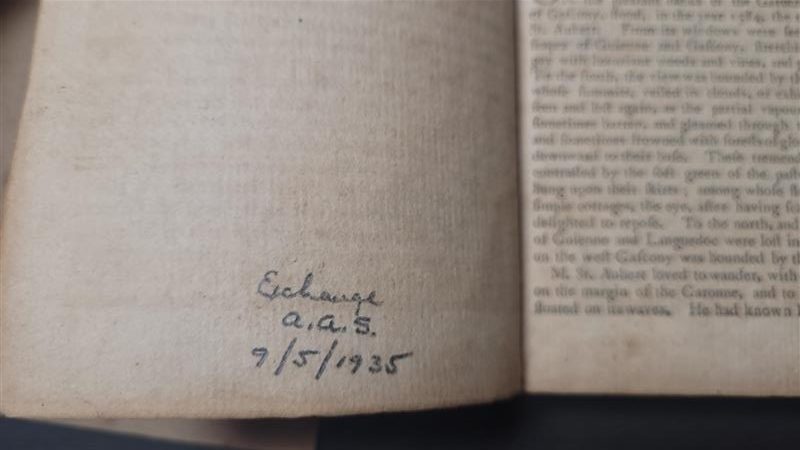

The MHS copy of The Mysteries of Udolpho was printed by Samuel Etheridge in Boston. A large number of contributors helped publish this book in a process known as combination. Combination publishing was very common at this time, as it allowed for groups of publishers to publish multi-volume, highly sought books together. This ensured that they all paid the same for the novel and protected against the potential loss of funding when printing a large number of books. The publishers for this copy are J. White, W. Spotswood, Thomas & Andrews, D. West, E. Larkin, W. P. Blake, J. West, and J. W. Folsom. In the very back of the first volume the name Johnson is inscribed, who may have been the original owner of this book. The MHS came into possession of the book in 1935 by an exchange with the American Antiquarian Society. The MHS also has a copy on microfilm and when I first came upon the book, it was unclear if it was the same printing. After a look at both, I determined that they were published in different years and places, with the physical book being an earlier edition by about 10 years.

The Mysteries of Udolpho is a three-volume book, detailing the adventures of a girl named Emily whose evil uncle whisks her away to Castle Udolpho deep in the mountains. I won’t spoil the suspense of the book for anyone else who wishes to explore it, but every day I’ve read some of the novel it has stayed with me after I left the MHS. I’ve enjoyed imagining what it would have been like to read the novel when it originally was published, as well as discovering how this book became part of the MHS’s collection. I would greatly recommend The Mysteries of Udolpho to anyone, and if you find yourself wanting to do as I did, come visit the MHS library to read this early printing of the famous novel.

This find would not have been possible without Reference Librarian Hannah Elder, who recommended Rebecca Romney’s book Jane Austen’s Bookshelf to me and then aided me in my research to learn more.