by Nate Grosjean, Visitor Services Coordinator

Finding myself at something of a perpetual loss for words these days, I decided to visit the MHS reference room in search of some new (rather, quite old) words to liven up my vocabulary. Fortunately for me, the library has a number of works pertaining to American slang terms, colloquialisms, and dialects.

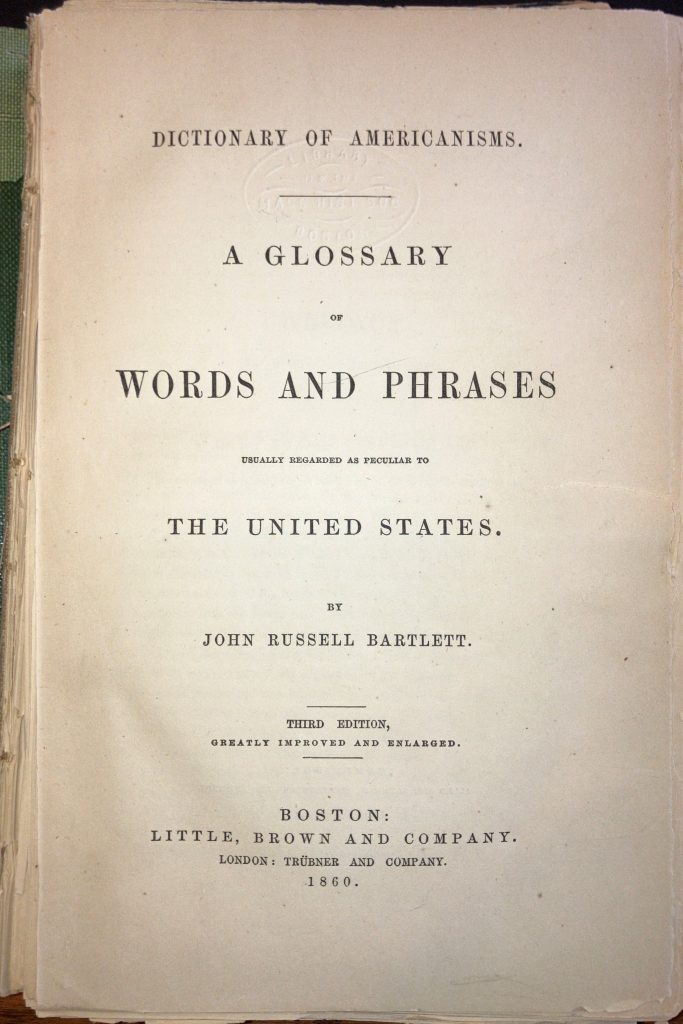

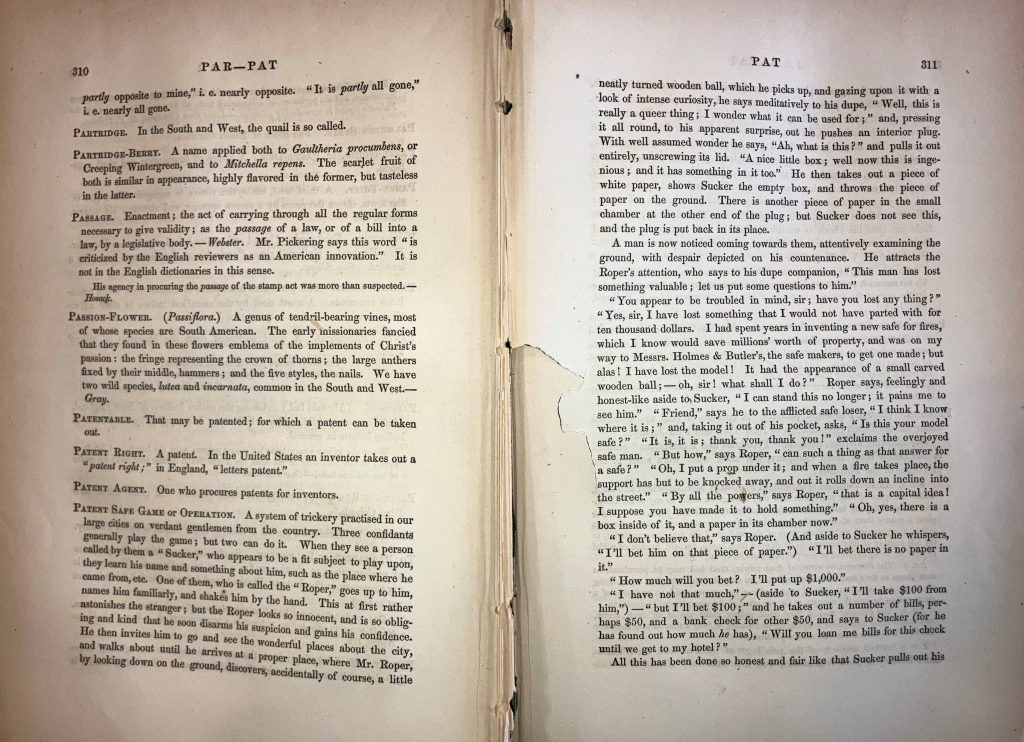

My favorite, John Russell Bartlett’s Dictionary of Americanisms: A Glossary of Words and Phrases Usually Regarded as Peculiar to the United States, 3rd ed., is a curious and complicated document. Published in 1860, just one year before the start of the Civil War, it draws together a wide range of phrases and expressions, from the botanical to the political to the whimsically unusual. Prior to its publication, Bartlett served for three years as “Commissioner on the Mexican Boundary,” a position which exposed him to the linguistic frontiers of south/western states like Texas, New Mexico, and California.

To illustrate his definitions, Bartlett included excerpts from a variety of sources from American literature, journalism, and print culture. Reading through this dictionary, one gets a sense of the many ways and spheres in which language developed: the project of creating a distinctly American language was entwined with the project of creating a distinctly American artistic and literary identity. Readers also get a hearty helping of intrigue, humor, and drama, and Bartlett’s best entries always include a story. Here are just a few!

“Acknowledge the corn. An expression of recent origin, which has now become very common. It means to confess or acknowledge a charge or imputation.”

Per the Pittsburgh Com. Advertiser, a man with two flatboats traveled to New Orleans “to try his fortune” selling corn and potatoes. Once there, he decided to go gambling (a beloved 19th-century vice), and lost spectacularly. Having no more money, he bet away his flatboats of corn and potatoes; only later did he learn that the flatboat of corn had sunk in the river. When his creditor arrived the next day to claim his winnings, the man craftily replied: “Stranger, I acknowledge the corn—take ‘em; but the potatoes you can’t have, by thunder!”

“Patent Safe Game or Operation. A system of trickery practised in our large cities on verdant gentlemen from the country.”

Citing Scientific American, Bartlett devotes almost two full pages to the explanation of this scheme. Three collaborators pose as a kind friend of the victim, the designer of a safe, and a cop. Their elaborate plot to rob their “Sucker” involves a small safe with a hidden compartment, a rigged gamble, a phony check, a chase sequence, and, of course, ample skullduggery. Sound complicated? It sure is! Read the full story at this link, complete with dramatic dialogue.

I’ll end with a selection of sounds from the dictionary. Onomatopoeia has a way of speaking for itself…

“Caswash! Dash! splash! The noise made by a body falling into the water. See cachunk.”

“Cachunk! A word like thump! describing the sound produced by the fall of a heavy body. Also written kerchunk! A number of fanciful onomatopoetic words of this sort are used in the South and West … These words are of recent origin.”

“Cawhalux! Whop! The noise made by a box on the ear.”

“Keslosh! Keswosh! Kewosh! Plash! Splash! The noise produced by a body falling flat into the water.”

“Kesouse! Souse! The noise made by a body falling from a small height into the water.”

“Keswollop! Flop! The noise made by a violent fall to the ground.”

Further Reading:

John Russell Bartlett. Dictionary of Americanisms: A Glossary of Words and Phrases Usually Regarded as Peculiar to the United States, 3rd edition. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1860.

Historical Note on the John Russell Bartlett Papers, Rhode Island Historical Society, Manuscripts Division.

Mitford M. Mathews, A Dictionary of Americanisms On Historical Principles. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1956.

Eric Partridge, ed. Paul Beale, A Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English, 8th ed. New York: Macmillan, 1984.