by Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

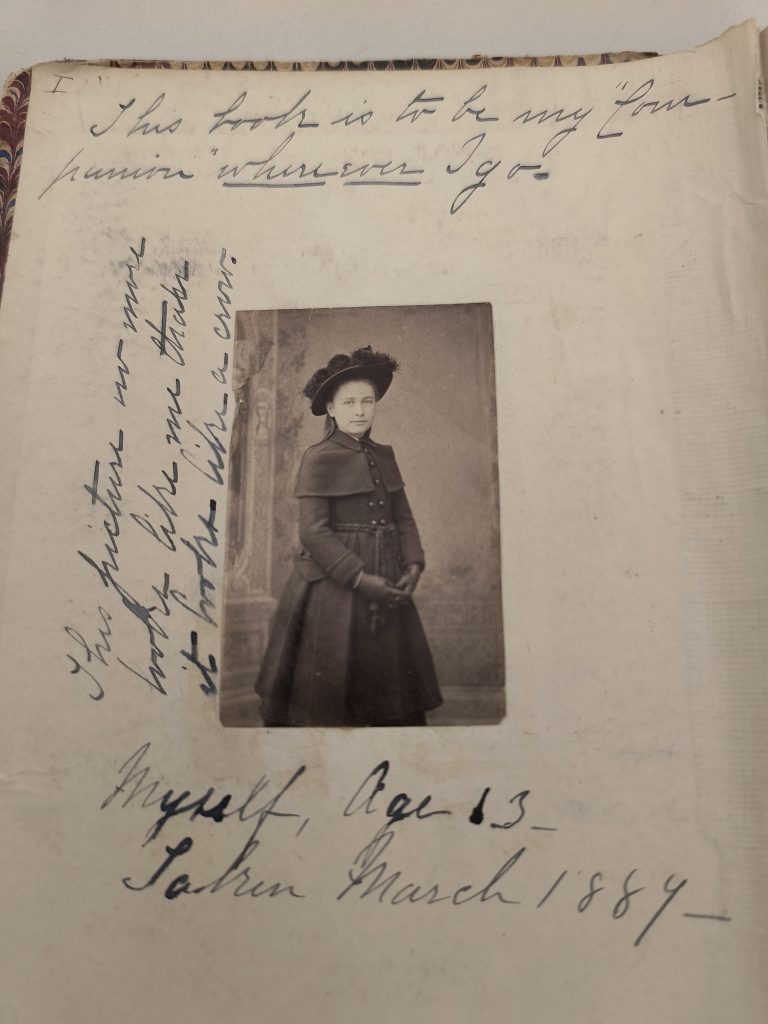

I’d like to introduce you to a young woman named Henrietta, whose diaries form part of the Stout family papers here at the MHS. This post will be the first in a multi-part series.

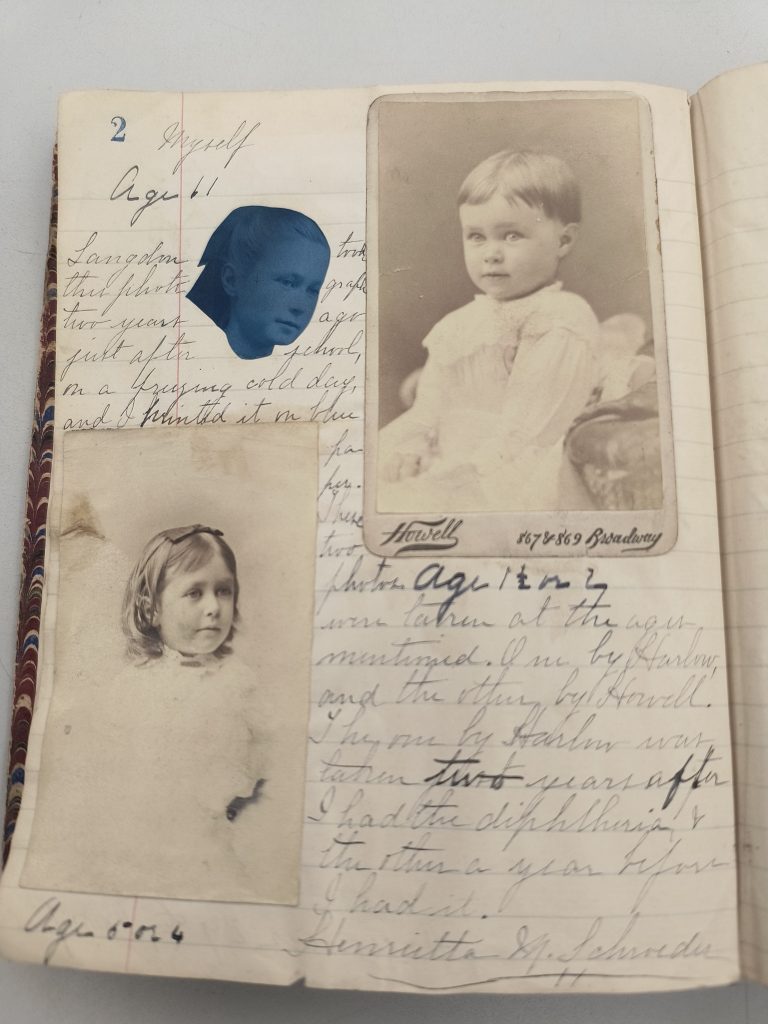

Henrietta Maria Schroeder, or “Yetta,” was born in New York on October 9, 1875. Her father, Francis Schroeder, had been a diplomat, ambassador to Sweden, and superintendent of the Astor Library. Francis had had two children with his first wife, Caroline (née Seaton), and four with his second wife, Lucy (née Langdon). Henrietta was Lucy’s third child.

The Stout collection includes four of Henrietta’s diaries, two kept as a young teenager and two kept in her twenties. The first starts on June 27, 1889, when she was thirteen and on a trip through Europe with her mother and three siblings, Langdon, Lucy, and Harry. I was immediately drawn to the diaries because of how lively, creative, and sometimes laugh-out-loud funny they are. I think Henrietta will sound familiar to anyone who knows (or is) a thirteen-year-old. To give you a taste of her style, here’s an entry she wrote about the ocean voyage to Europe.

In the first place I was ill: not actively so, but I was ill. Days and days passed which seemed like years, but still I was ill, at last Mamma called the doctor, and such a doctor, […] and he gave me some lime water, & some awful stuff that tasted just like pepper and vinegar, but he cured me just the same! […] He is the most “blasted English don cher know” thing I ever saw, and I burst out laughing every time I see him. He waxes his mustache into spears about 4 inches long.

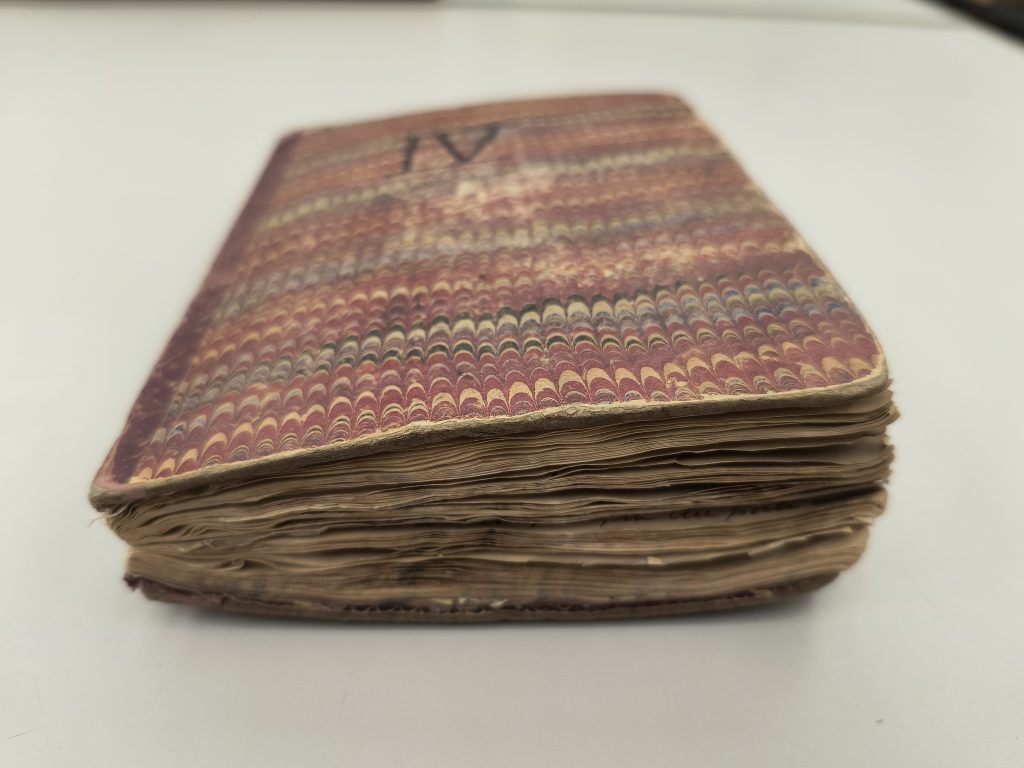

In addition to Henrietta’s entertaining run-on sentences and stream-of-consciousness anecdotes, the diaries also contain her original sketches and objects she added as illustrations or keepsakes. Here’s a partial list of items she pasted or pinned to the pages: letters, photographs, ticket stubs, menus, flowers, feathers, leaves, ribbons, wax seals, a piece of lead from a pencil-making factory, a piece of stone from Chester Cathedral, and a pouch of sand from the shores of Loch Katrine. You can see how overstuffed the volume is.

As you can imagine, volumes like this are a preservation nightmare for archivists and conservators. Organic and acidic material will stain and degrade the pages. In most cases, all we have the time and the resources to do is stabilize the volume and prevent any further deterioration by housing it in an appropriate container and storing it in our climate-controlled stacks. We also often interleave the pages with tissue to protect them.

But the very same thing that makes these diaries tricky from a preservation standpoint also makes them interesting from a historical standpoint. The inserted material is fully integrated into the narrative, adding context and (literal!) texture to Henrietta’s stories. I love how free-wheeling and genre-bending it all is, this first diary in particular. Henrietta has taken a volume that cost her, she says, just 28 cents and turned it into a unique, interesting, and very fun historical document.

I look forward to telling you more about Henrietta in future Beehive posts.