by Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

This is the second part of a series. Read Part I here.

A few weeks ago, I introduced you to a precocious 13-year-old girl named Henrietta Schroeder. Her diaries in the Stout family papers are a really fun read.

When we last saw Henrietta, it was June 1889, and she was on her way to Europe on the S.S. Alaska with her mother, sister Lucy, and two brothers Langdon and Harry. Her father Francis Schroeder had died three years before.

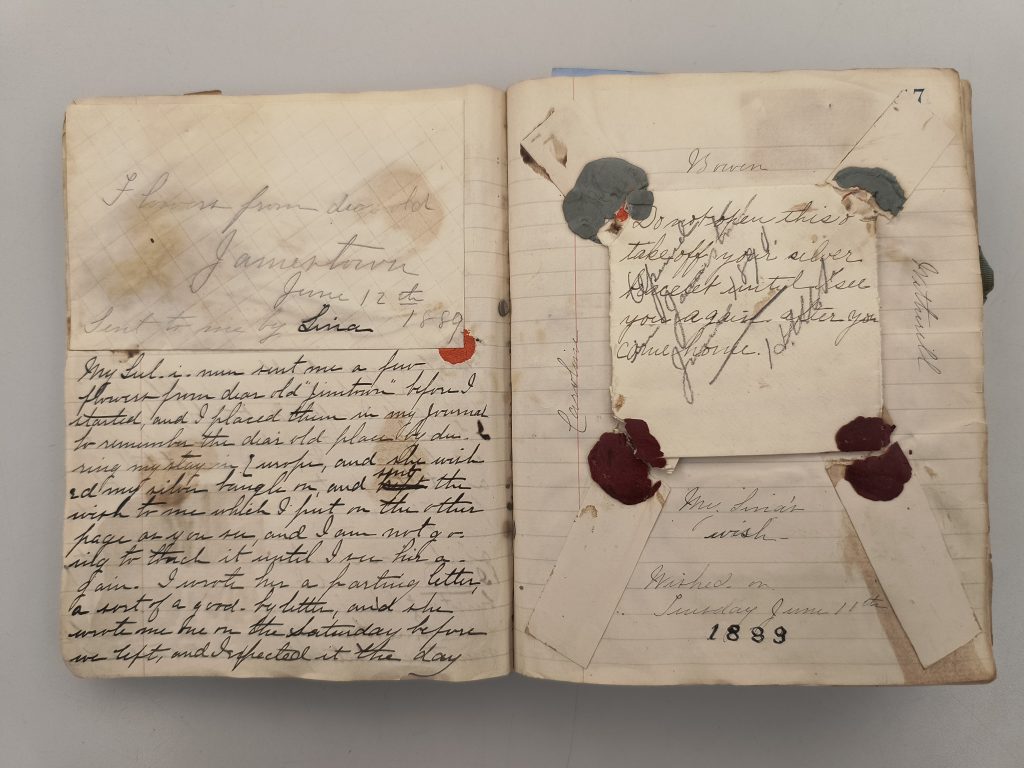

Henrietta had a rough voyage; she got both sunburned and seasick (though “not actively so”!) Worse still was how much she missed her “most beloved and most loving friend” Caroline Bowen Wetherill, or “Lina.” Caroline was nine months younger than Henrietta and lived in Philadelphia. My best guess is that the two girls met in Jamestown, R.I., a popular vacation destination at the time. Henrietta’s diary includes a photograph of Jamestown and references to seeing Caroline there.

Henrietta wrote often in her diary about her “darling” Caroline. She described their last goodbye (“the last figure I saw kissing her hand to me through the window of the closed carriage”) and attached on facing pages both some flowers Caroline had sent and a folded-up “wish” to be opened when they saw each other again. The friends even had pet names for each other: “Lul-i-nun” for Caroline and “Yud-e-tub” for Henrietta. Try as I might, I couldn’t identify the source of the names.

After landing at Liverpool, the Schroeder family visited Chester, England, before traveling north to the Lake District. Henrietta seemed to enjoy sightseeing, and though she got some details wrong, her breathless descriptions would make an entertaining guidebook. She was especially awestruck by how old everything was.

While touring Chester Cathedral, which was undergoing renovation, Henrietta took—with the permission of the guide—a centuries-old piece of crumbling wall as a memento. The Schroeders also visited Chester’s ancient Roman baths, and Henrietta exclaimed, “just think, before Christ!” Later at their Lake District hotel, she slept in a large canopy bed that, she wrote excitedly, dated back to the reign of Elizabeth I. In a quieter moment, she summed it up this way: “No matter where you go, you step on graves.”

It’s around this time we get a glimpse of another side of Henrietta: her temper. One day when Lucy and Langdon went rowing with their mother, Henrietta stayed back with her younger brother Harry. Unfortunately the rowing party didn’t come back when they said they would.

“I was simply frightened out of my wits […] Twelve came, and still not a sign of them, and then half past twelve, and then I thought surely they were drowned or something, and I began planning out what to sell, to get a little money and pay for the bills of the hotel, and to telegraph to Grandpa for some money, and then one o’clock came, and with it in sailed Lucy as large as life […] I tell you, I gave it to her!!!!!!”

The stream-of-consciousness style of Henrietta’s diaries sometimes makes it hard to pinpoint exact dates and places, but July 4, 1889, found her at Lake Hotel in Keswick. She was enjoying the trip, but felt disappointed at having to spend Independence Day in the U.K., writing, “It will seem so horrid not to have any racket, you know it is a black day over here in England. Oh! how mean!” She celebrated by rising early, going into the woods, and belting out patriotic songs to no one in particular.

I hope you’ll join me next time for more of Henrietta’s adventures.