By Anna Clutterbuck-Cook, Reader Services

Today we return to the 1917 diary of Gertrude Codman Carter. You may read the previous entries here:

Introduction | January | February | March | April | May

June | July | August

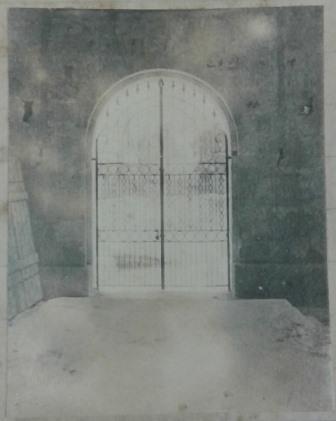

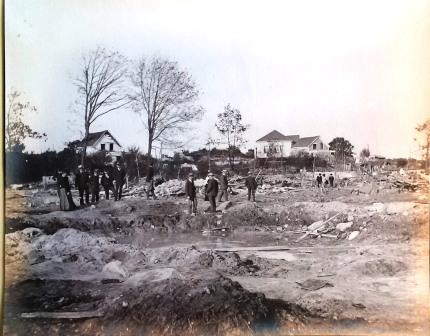

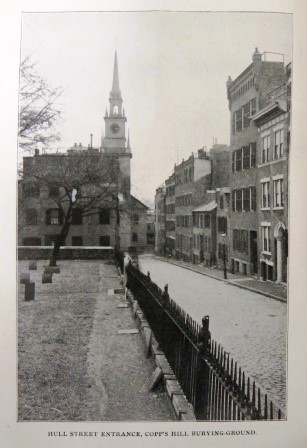

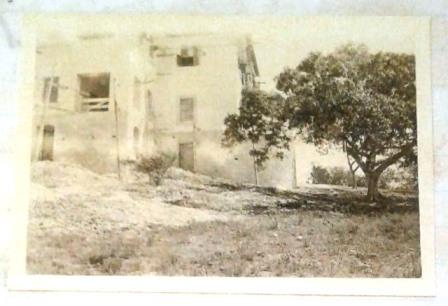

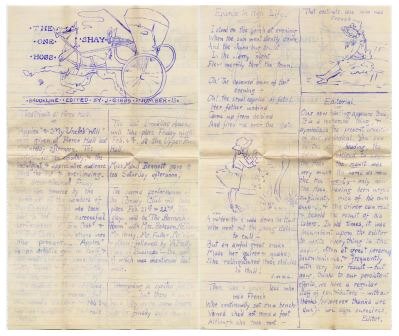

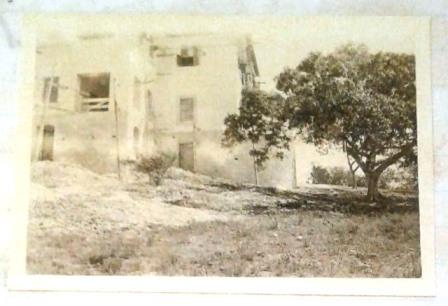

September’s entries are heavily illustrated with drawings and photographs. Having just moved into Ilaro, Gertrude supervises continued construction at the site while managing the household in her husband’s absence. Domestic drama includes the “letting go” of a servant who “couldn’t stand the stairs” of the new residence, and the hiring of a replacement — actions that do not endear Gertrude to her staff.

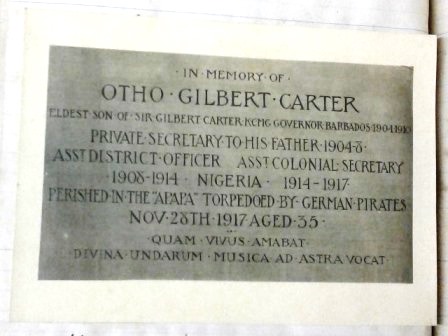

The war intrudes on the household once again as Gertrude receives a letter from the Colonial Secretary’s office with instruction for the conscription of her automobile in the event of an attack by the enemy. Amidst it all, Gertude continues to live a life of social obligation and voluntary labor as part of the Self-Help group and other island committees.

* * *

Sept 1.

Sent Barbara $50.

Moved into Ilaro. Toppin & Small, Edith & Norah & Ada, who couldn’t stand the stairs after all. We had our first dinner there on the marble verandah & it was quite lovely.

Sept 2.

Unpacked & tried to feel settled. John & I slept in the [illegible] room. Such fun.

Sept 3.

Rising bell at 7 a.m. & the house full up with very busy workmen,clanging & banging, sawing and jawing, [missing fragment], taping & scraping, patching & scratching, latching & detaching whatever was wrong, which happened after.

Our meal was rather full of coral dust but Topping was zealous & managed quite wonderfully for his age.

Sept 4.

Marked out servants quarters.

Mrs. Skeet came by to look at it.

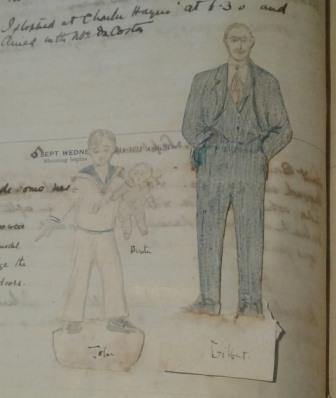

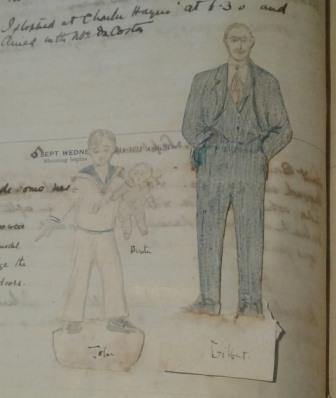

I stopped at Charles Hayes at 6.30 and dined with Mrs. DaCosta.

Sept 5.

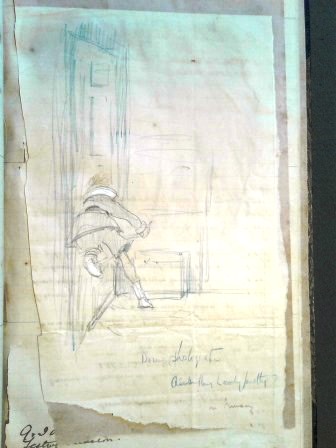

These little figures were made for a scale model of Ilaro, to gauge the height and width of doors.

Sept 6.

10.30 Civic Circle met at [illegible] Park.

Sept 7.

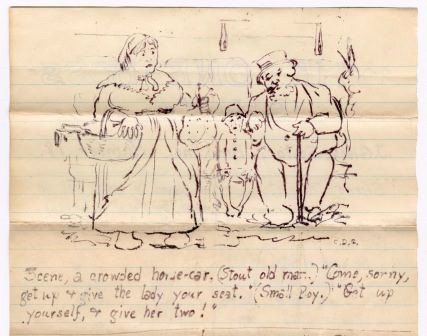

Called Chelston for washing. Gave up Ada & hired Rosina, a girl of the Cawfields. This, it appears, was considered by everyone below stairs as a fearful faux pas. I got no less than three anonymous letters on the subject, which outraged Bailey beyond measure.

Sept 8.

John began a letter & headed it “Ilaro Court limited.”

“What does it mean, John?” — “Oh – just what it means on the honey bottle!”

Sept 9.

Laddie to tea & a little [illegible] out. He is very appreciative of my powers as an architect.

Sept 10.

Miss Hatfield called about the Easter Féte for my advice. I became a sort of unofficial Chairman of the Committee & advised in a Sybelline manner.

Sept 11.

To photographer with John. [illegible] had sticks — both of them.

John Carter

4.30 to bathe at Mrs. Harold Whytes.

12 Sept.

Self-Help meeting

Miss [illegible] again.

Laddie later for a spin.

13 Sept.

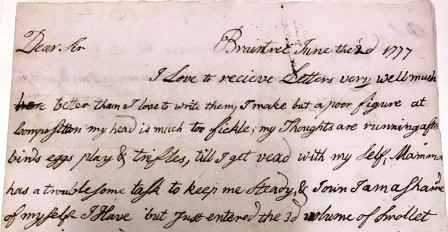

[entry obscured by a typescript letter from the Colonial Secretary’s Office]

CONFIDENTIAL.

CIRCULAR.

No. 19.

Colonial Secretary’s Office, Barbados.

14th September 1917.

Madam,

I am directed by the Governor to inform you that the Defence Committee will require transport facilities for the Defence Force in case of enemy attack. On the “Alarm” being sounded you are requested to send your motor car No. M158 to [illegible] where it will be available for use in accordance with order issued by the officers of the Force.

2. A driver, and the necessary supply of Petrol, spare tyres, etc. should be available with the car.

3. The Government undertake to recommend to the Legislature that compensation be paid for damage caused by enemy action.

4. The “alarm” consists of the firing of five rockets from the Harbour Police Station, and the firing of powder charges from two 9 pounder guns, at the Garrison and the Reef respectively.

5. The Defence Committee’s recommendations are based on the assumption that you will readily co-operate with them in arranging transport facilities in case of attack. His Excellency has therefore asked me to obtain from you a statement to the effect that you have made arrangement of a kind to ensure prompt dispatch of the car whenever the “Alarm” is sounded.

I have the honor to be,

Madam,

Your most obedient servant,

T.E. Fell,

Colonial Secretary.

Sept 14.

Ditto.

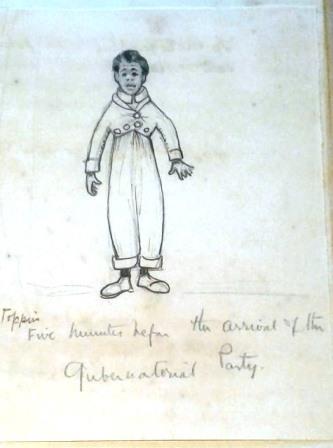

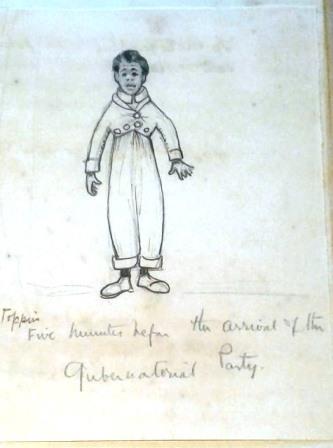

“Toppin. Five minutes before the arrival of the Gubernatorial Party.”

Sept 15

The Probyns came to see the house.

Sept 16.

Mr & Mrs [illegible] to see house.

I dined at the Laurie Piles.

Sept 17.

Auction inspection.

I dined at the Harold Whytes’ – a most amusing evening. Harold Whyte & Laddy & Mr Fell played an uproarious game of bridge in which they were respectfully alluded to as the army, the vestry, and the government & every now and then a large land crab would come in & sport about the floor. I took Mr Fell & Colonel Humphreys home & my car began to wheeze just after that & I found that it was in for a long illness this time.

Sept 18.

Mrs [illegible] came & fetched up & took me back to Brittons for bitters.

Sept 19.

Hired a car & took Mrs. Carpenter to an auction in the country. We had a picnic lunch. Great fun.

Sept 27.

Mrs Humphreys & Doreen to tea. Rained heavily & we had no where to go but in & then it was only a courtyard.

I dined with the [illegible]. Jolly evening.

Sept 28.

Busy on the house.

Laddy telephoned.

Sept 29.

[illegible]. Laddy had a picnic & took me to Bleak House. Had [illegible] drove Mrs Carpenter. We had bitters & sandwiches & a great time.

Sept 30.

Laddie drove me out to the Charlie Haynes’. After dinner we worked all of us on the [illegible]. We saw Lady [illegible] toes out of the window!

* * *

As always, if you are interested in viewing the diary or letters yourself, in our library, or have other questions about the collection please visit the library or contact a member of the library staff for further assistance.