By Grace Wagner, Reader Services

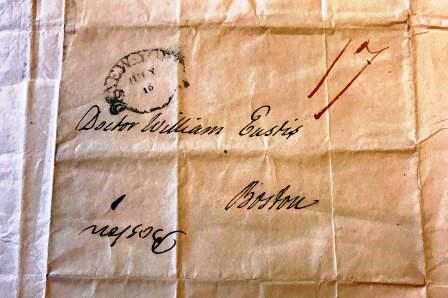

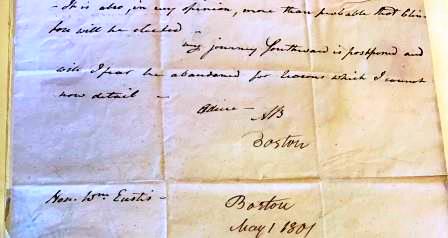

A letter addressed to Doctor William Eustis of Boston, MA.

In a box of letters addressed to Doctor William Eustis, a physician and politician who lived in Boston, some of the political and personal musings of Aaron Burr (Aaron Burr letters, 1777-1802) can be found at MHS. The bulk of letters were written between 1794-1802, right in the midst of Burr’s political campaigns (in 1796 and 1800) for the United States presidency and the height of his political ambition.

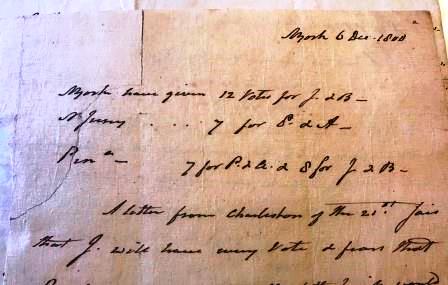

As might be expected, Burr references his political opponents and the forthcoming elections in his letters, but the focus of his letters is primarily concerned with counting votes. Burr marks the differences between himself, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and (Charles and Thomas) Pinckney through numbers rather than political views:

“If A. [Adams] has all the Eastern votes he has 69 north of Potomac — If Jeffn [Jefferson] has all the Southern votes, he will has 70…” [December 16, 1796]

“It is now probable that N Jersey will not give a vote for A. [Adams]” [July 15, 1800]

“…both Hampton & Alston write positively that Jefferson will have the eight votes of that State — both are however apprehensive that P. [Charles Pinckney] will also have them…” [December 5, 1800]

Burr counts up the votes

In the 1796 election, Burr finished abysmally in comparison to his political opponents: Adams led with 71 votes, Jefferson a close second with 68, Thomas Pinckney in third with 59, and Burr in last place with only 30 votes. Alexander Hamilton wrote “the event will not a little mortify Burr.”[i] While this assessment may have been true, it was not the reaction Burr displayed publically or even in private letters to his friends. Burr’s letters following the election demonstrate that he remained committed to playing a numbers game as before. To Eustis, he writes: “I have no doubt however but he [Adams] will be the Pres’t — and I am very glad that your people had the discretion to throw away some votes rather than give them to P [Thomas Pinckney]” [December 18th, 1796].

As it turns out, Burr had good reason to concern himself with election numbers. In the election of 1800, this tactic, along with some clever political maneuvering, helped Burr come very close to winning the presidency. This was partly due to the way elections were run in the early days of the United States. At this time, presidents and vice presidents did not run on a single ticket. Rather, the man with the most votes became president and the runner-up became vice president. This meant that in addition to Burr running against candidates of the opposing party, Adams and Charles Pinckney (Federalist Party), he was also effectively running against a candidate of his own party, Jefferson (Democratic-Republican Party).

Burr’s campaigning became particularly rampant in the summer of 1800. Hamilton described Burr as “intriguing with all his might in New Jersey, Rhode Island, and Vermont,” and warned “there is a possibility of some success in his intrigues.”[ii] Judging by the cagey, secretive nature of Burr’s letters at this time, Hamilton may not have been far off base in his assessment. On July 1, 1800, Burr writes cryptically to Eustis: “The thing is preparing but not yet done — the labor exceeds what I had imagined — It will be finished & forwarded in the course of this week — I have nothing else now to say which I dare say in this way.”

When the votes had been cast, Burr and Jefferson were tied with 73 votes apiece, leading to a contentious run-off vote in the House of Representatives to determine which one would be president. James Cheetham, a newspaper editor of American Citizen, published a long, unfavorable pamphlet about Burr’s actions during the election, which included the following passage:

Cheetham attacks Burr

“It is fearful to reflect upon what our condition would, in all probability be, were Mr. Burr at the head of our government….It cannot be concealed that he is a man of desperate fortune; bold, enterprizing, ambitious, and intriguing; thrifting for military glory and Bonapartian fame. A man of no fixed principle, no consistency of character, of contracted views as a politician, of boundless vanity, and listless of the public good…”[iii]

Although Burr lost to Jefferson in the House vote in February 1801, the way Burr ran his 1800 political campaign helped change the way that political elections were conducted in the future. In one of the last letters written to Eustis in our collection, Burr closes his letter with a typically cryptic remark: “My journey Southward is postponed and will I fear be abandoned for reasons which I cannot now detail — ” [August 1, 1801].

Burr remains secretive

The above transcriptions are preliminary and are not meant to be authoritative. For more information about the election of 1800 and our “intriguing” Founding Fathers, check out the sources below or visit MHS to explore the collections!

[i] Van der Linden, Frank. “The turning point: Jefferson’s battle for the Presidency,” Golden, Colorado: Fulcrum Publishing, 2000. 32.

[ii] Larson, Edward J. “A magnificent catastrophe: the tumultuous election of 1800, America’s first presidential campaign,” New York: Free Press, 2007. 159.

[iii] Cheetham, James. “A narrative of the suppression by Col. Burr of the History of the administration of John Adams, late president of the United States, written by John Wood” New York: Printed by Denniston and Cheetham, 1802. 39.