By Anna Clutterbuck-Cook, Reader Services

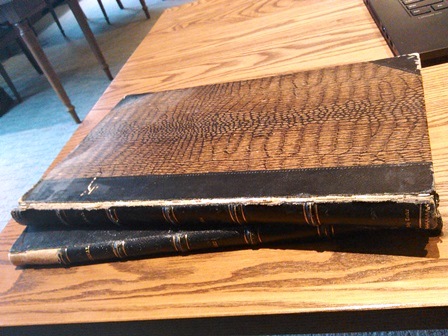

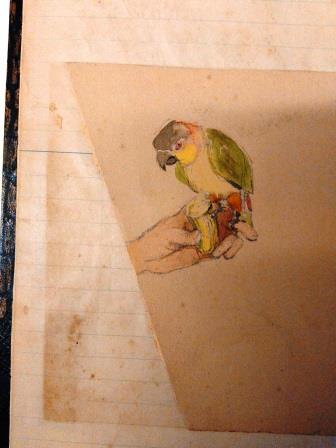

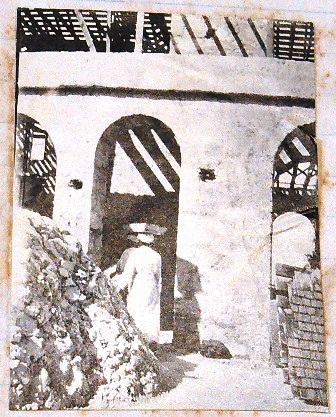

Today we return to the 1917 diary of Gertrude Codman Carter — artist, wife of Sir Gilbert Thomas Carter, a British colonial official, and mother to a young son, John Codman Carter. In February of 1917 the family resided in Barbados where Gertrude spent her days overseeing the construction of Ilaro Court, the family residence she had designed, and participating in a wide variety of social engagements.

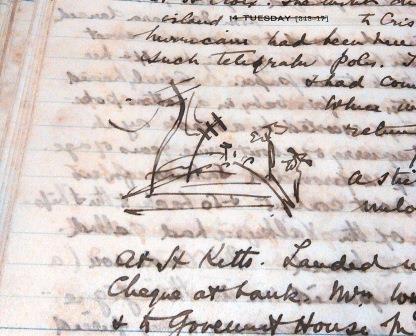

Although physically far removed from the war raging in Europe, the family and their neighbors were intimately connected to the violence across the Atlantic. On February 18th, Gertrude interrupts the short-form structure of her typical diary entries to give an account of the injury and later loss of a neighbor’s son in battle.

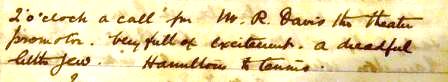

While diaries invite us to see the world through the eyes of the diarist, that perspective is not always a comfortable one. On February 17th, she notes that she took her son John and a friend to a carnival dressed as a pirate and an “Indian Chief.” Toward the end of the month, between describing social calls and an afternoon playing tennis, Gertrude sees fit to remark that she received a call from “a dreadful little Jew. These casual displays of racism and anti-semitism remind us of the larger British and American imperial hierarchies within which this white New England woman was embedded.

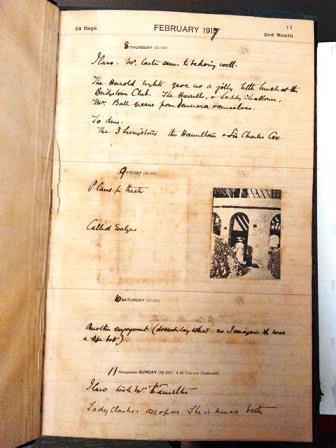

*** February 1917 ***

8 Feb. Ilaro. Mr. Carter seems to be doing well.

The Harold [Whytes?] gave us a jolly little lunch at the Bridgetown Club. The Harrells, & Lady Challum, Mrs. Ball Greene from [illegible] & ourselves.

9 Feb. Plans for theatre. Called Evelyns.

10 Feb. Another engagement (doesn’t say what – so I imagine it was a [illegible]).

11 Feb. Ilaro. Took [illegible].

Lady Clark’s [illegible]. She is much better.

12 Feb. Ilaro. Called Skeet.

13. Ilaro. John in nursery window.

14 Feb. Women Self-Help Committee Meeting.

15 Feb. (What did I do all this time? Calendar says nothing). Government House at home.

16 Feb. Ilaro. 3 [illegible] Called [illegible] Mrs. Cullen. 9. Hall Clarks. Personal [illegible].

17 Feb. Auction at Mandon. Children’s carnival at [illegible] Park. John as a Pirate walked with Lyall as an Indian Chief. Took Hamilton.

18 Feb. E.F.S. Bowen to see house.

To Wm. Mannings to tea. A lovely afternoon & I took the Hamiltons to see the place. Mrs. Manning was very cheery having just received a letter from her son John saying “The Germans seem to be out of the stuff they need to kill me!” After tea on the verandah we went out on the lawn. The telephone bell rang & Mrs. Manning trotted off to answer it. I saw her coming back with her head up like a brave soldier. “Bad news,” she said, “John is wounded. They are sending up the cable. I walked up and down with her while the others melted away. Presently a boy on a bicycle came wheeling up the drive & the butler with a tragic face brought the orange envelope across the lawn. The sun was savagely bright & the yellow and blue macaw shrieked as he swung on his perch. I opened it & read it to her.

“Regret to inform you Lieutenant John Manning brought in dressing station severely wounded. 17th instant.”

Mr. Sam Manning came across the lawn: his face was impassive & he still held a fossil shell in his hand. Mrs. Manning was sobbing in my arms. She raised her head & said, “Sam. Wasn’t it odd? You remember yesterday afternoon?” “Indeed yes,” said the husband to me. “Mrs. Manning was sitting in her room & she looked up & saw John come in.”

(There seems to have been no doubt that this was a real case of telepathy, that the dearly loved son appeared to his mother of whom he thought constantly to say goodbye. It does not to me [impair?] the example of telepathy the fact that the man who came in to Mrs. Mannings room was her other son Herbert. She saw the face of John later form upon the face of Herbert for only a few moments.)

I sat with Mrs. Manning for an hour, trying vainly to give comfort. “He isn’t missing dear Mrs. Manning, he’s comfortable. They are taking care of him, he is at the dressing station. They’ll do everything for him.” But the mother shook her head. “He will die,” she said slowly. It was to say goodbye that he came yesterday.”

And indeed I was not surprised the next day to see the flags of the town at half mast for the boy who had gone. It was to me significant that his farewell should have been to his mother rather than the graceful little wife who married him in a rush & repented it afterward.

19 Feb. A nice swim. Called [illegible] etc. etc. in P.M.

Lady Godfrey & Mrs. Austin [illegible]. Dined at the Hamilton who have moved into [illegible].

20 Feb. Tea at Mrs. Burton’s. Stone carving.

21 Feb. Took John to make calls.

22 Feb. Another nice swim. [illegible] at 11. Mrs. Clifton [Whyte’s?] party [for?] Edna

23 Feb. Took Mrs. Burton to Ilaro. Some nice [gossetts?] to Lewis. Colonel G’s son’s [fiancee?] (he was killed at Ypres) a Miss [illegible].

[illegible] on theatre plans.

24 Feb. [illegible] Tea at the Felix Hayley’s. Theatre plans.

25 Feb. Meet Mr. Bowen & Mr. Carlin at Ilaro about sash weights. Called Wilkinson’s & Laws.

[illegible] round plan.

26 Feb. Burtons at 9. House at 10. 2 o’clock a call from Mr. R. Davis the theatre promoter. Very full of excitement. A dreadful little Jew. Hamiltons to tennis.

27 Feb. Electricity at 11. At Ilaro.

2 o’clock meeting of the Theatre Committee. [illegible] outside plan of theater for model. Worked rest of p.m.

28. Feb. Worked on [illegible] for theater. 4.30 Civic [illegible] at the Budges.

Dined at the Hamilton & played Pirate [illegible].

***

If you are interested in viewing the diary yourself, in our library, or have other questions about the collection please visit the library or contact a member of the library staff for further assistance.

These transcriptions are preliminary and not meant to be authoritative. In all cases where a word could not be contextually surmised [illegible] has been inserted in its place.