By Anna J. Clutterbuck Cook, Reader Services

Today, we return to the line-a-day diary of Margaret Russell. You can read previous installments here:

January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October

As winter approaches, Margaret Russell’s activities shift from the north shore back to Boston, where she attends lectures and concerts on a regular basis as well as noting a regular round of visits to family and friends.

On November 8th she notes that she spent time packing in the morning and then left for New York City on the five o’clock train. Her destination was ultimately Hot Springs, North Carolina where she found “pleasant rooms” waiting for her, “lovely weather,” and “very pleasant people.” She stayed for almost two weeks enjoying the balmy weather and sunshine before returning to the “bitter cold” of Boston via New York. On the 29th she attended the theatre, seeing the romantic comedy The Great Lover which had had its run on Broadway from November 1915 to June 2016. “Very amusing” our diarist notes.

As we round out this year in the life of Margaret Russell, I have begun exploring my options for a 1917 diary to transcribe; stay tuned for a December blog post introducing our 2017 diarist and diary before we see what the year 1917 brings for our chosen Bostonian.

In the meantime, without further ado, here’s Margaret in her own words.

* * *

November 1916*

1 Nov. Wednesday – All Saint’s Service. Mrs. Ward’s opening talk. First Holman meeting at Mrs. Allen’s. Ward reception for Perkins girl.

2 Nov. Thursday – Shopping. Went to Swampscott. Dined at Mrs. Bell’s.

3 Nov. Friday – Went to Milton & called at Sarah Hughes & Hester Cunningham. Dined at S. Bradley with Mr & Mrs Locke.

4 Nov. Saturday – Errands. To see Aunt Emma, Stephen Wild’s [sic] & Mrs. Walcott. Country still very beautiful.

5 Nov. Sunday – Church – Lunched at H.G.C’s.

6 Nov. Monday – Mary. Lunched with Marian.

7 Nov. Tuesday.

8 Nov. Wednesday – Packing. Went H. Cushing’s memorial exhibition. Left for N.Y. on five o’ck. Went to Colony Club.

9 Nov. Shopping – Lunched at Mary Amory’s. Met Mrs. [illegible] on five oc to Hot Springs.

10 Nov. Arrived 9.30 (hour late) Pleasant rooms. Have cold so kept quiet. Mrs. S. busy with baths – Movies in the evening.

11 Nov. Saturday – Lovely weather keep out as much as possible. Very pleasant people.

12 Nov. Rainy – Went to church. Most of P.M. in my room.

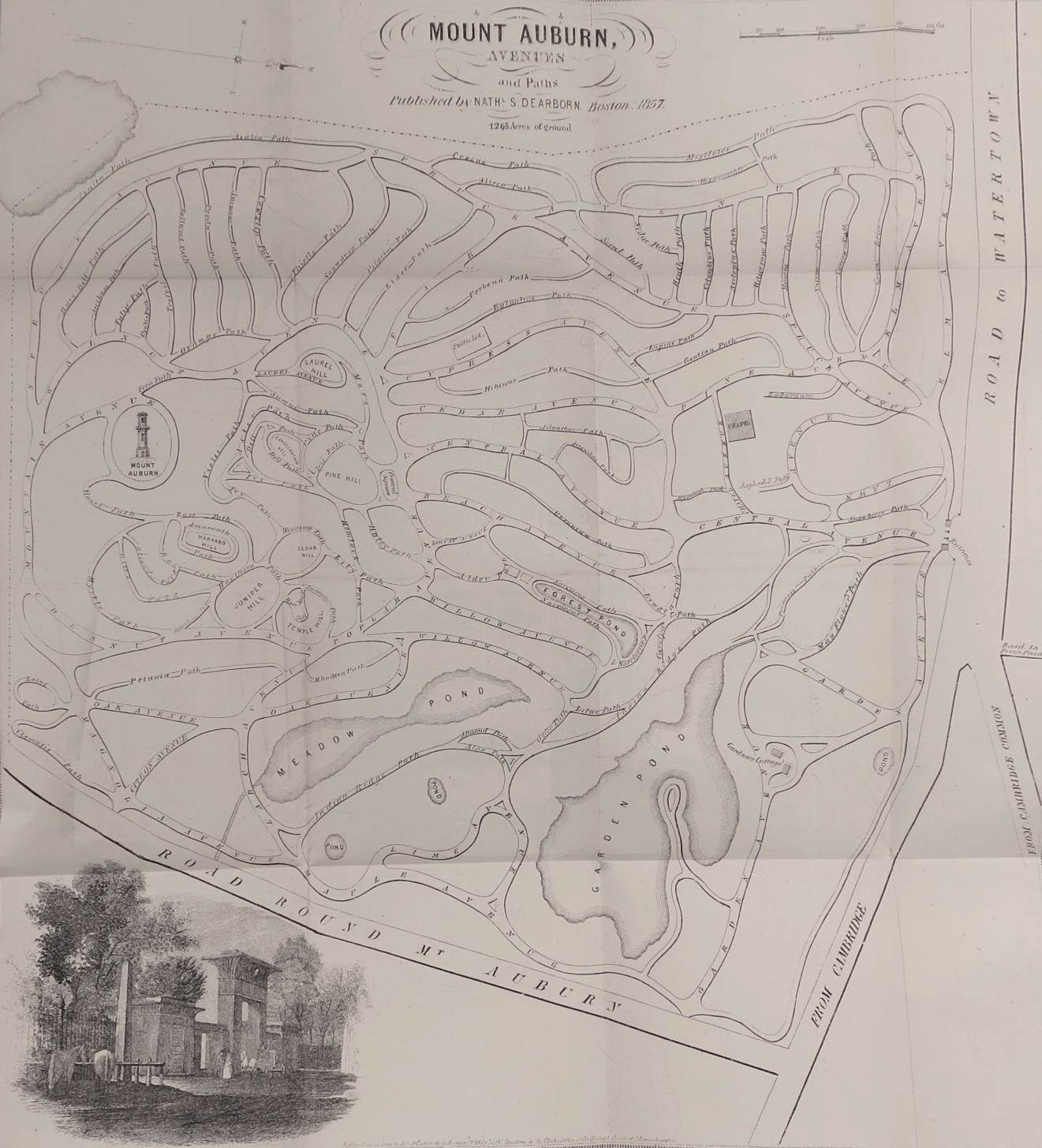

13 Nov. Monday – Walked up Delafield Path. Warm & lovely. Took beautiful drive round mountain.

14 Nov. Tuesday- Cloudy & cold. Wrote letters & rested. Walked with Mr. Chapin to dairy.

15 Nov. Wednesday – We walked to Boone Cabin & lunched […] sun on ground. Feeling better.

16 Nov. Thursday. Still very cold. Took long walk. We drove to Flag Rock in P.M. but it was too hazy to see far.

17 Nov. Friday – Warmer. Took walk in the morning. Drove to Dunn’s Gap.

18 Nov. Saturday. Drove to Healing Springs & walked through Cascades, home to lunch. Sat out in the sun.

19 Nov. Sunday – Church & then walked to Tall Gate. Took the jungle drive. Concert in the evening.

20 Nov. Monday – Walked up Sunset Hill. Sat in piazza in the sun with pleasant people.

21 Nov. Tuesday – Drove to [illegible] for lunch, took Miss Newell.

22 Nov. Wednesday – Took a long walk in morn. After lunch sat in sun. Movies in the evening. Like early autumn.

23 Nov. Packing. Heavy showers so did not go out. Tea at five with Mrs. Berwind & all our friends. Left at 6.30 for N. Y.

24 Nov. Friday – Arrived in N. Y. 9.30. Mrs. Sibley drove me to Colony Club but had no room. Took walk & left on 1 oc for home.

25 Nov. Saturday – Shopping & doing errands. Drove to Swampscott, bitter cold. Lovely concert in the evening.

26 Nov. Sunday – Church. Lunched at HGC. Short walk still cold. Family to dine.

27 Nov. Monday – Mary, lunch with Marian. Went out to see Aunt Emma & leave flowers for Mrs. J. M. Cadman.

28 Nov. Tuesday – Errands on foot & meeting at E&E. Took long drive & dined at C’s. Meeting of new opera co.

29 Nov. Wednesday – Went to see the Great Lover with the Parkmans. Very amusing.

30 Nov. Thursday. Church then to dine at Sallie A’s. Raining so drove back with Marian. Dined at HGC’s. Four Neilsons came.

* * *

If you are interested in viewing the diary in person in our library or have other questions about the collection, please visit the library or contact a member of the library staff for further assistance.

*Please note that the diary transcription is a rough-and-ready version, not an authoritative transcript. Researchers wishing to use the diary in the course of their own work should verify the version found here with the manuscript original.