By Kimberly Arleth, Reader Services

Growing up in a small Midwestern town in rural Minnesota, I had what some might say was a quintessential upbringing — complete with a horse farm! This, however, was a long time ago. Moving to the Twin Cities to attend college, and more recently Boston three months ago, I thought I left whatever rural nature I had in me behind for ‘bigger and better’ things. Yet, being in the ‘big city’ makes me nostalgic for my country childhood.

As I began to explore the extensive collections at the MHS, I found myself drawn to a number of items related to cities and working horses in the nineteenth century – particularly the ‘Horse Railroads’. This material intrigued me having worked with horses for the first thirteen years of my life and the romantic notions of a city filled with horse drawn carriages and trolley cars. Mentioning this to one of my coworkers, the joke became that after last winter’s transit halt, it might not be a bad idea to return to these simpler roots. I wonder though, would New England snowstorms really be any easier to weather if the city ran on hooves rather than rails?

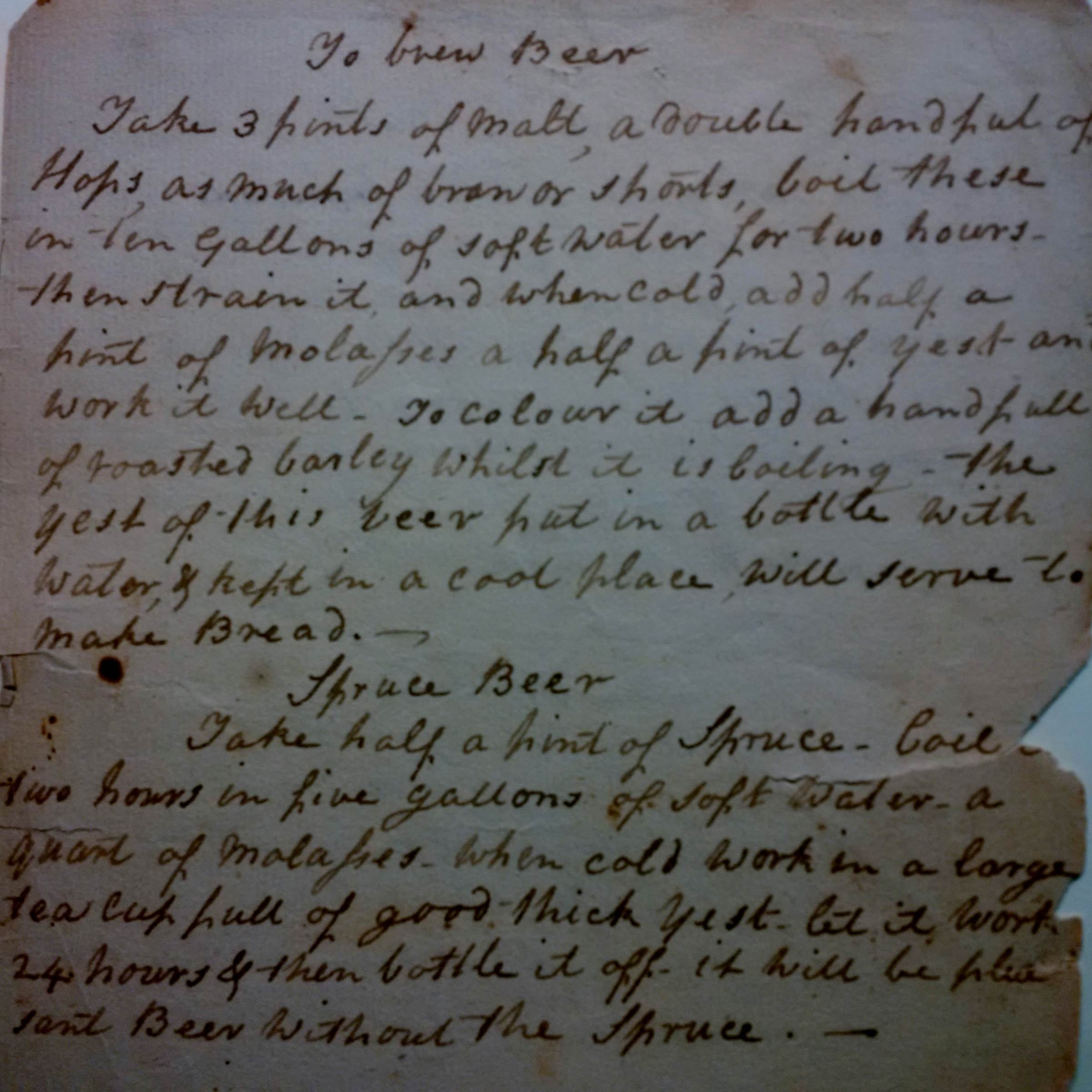

Cover of Rules and regulations for the government of horse railroads, 1865. Boston (Mass.). Board of Aldermen.

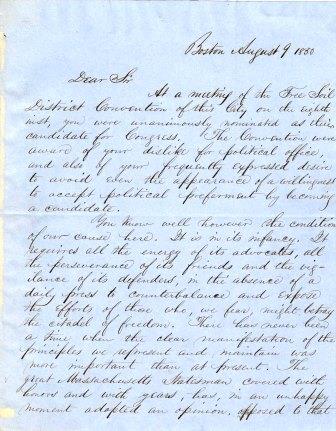

A 1865 pamphlet, “Rules and Regulations for the Government of Horse Railroads”, helped to shed some light on this question. It was declared, by an act of the legislature in 1864, that regulations on horse railroads were needed to address “the interest and convenience of the public.” Any instance of noncompliance with the rules would result in a penalty of “not more than five hundred dollars for each offence.” Today this would be a maximum fine of seven thousand dollars per offence, not a small sum at all!

Much of the language in the rules and regulations pertain to maximum speeds allowed (five miles per hour in Boston proper, seven miles per hour outside of these city limits, and a walking gait when taking corners), and all the restrictions around when stopping of the horse railroad car is allowed and for how long. Most restrictions prohibited the stopping of the car for longer than one minute between “six o’clock in the forenoon and eight o’clock in the afternoon” (6:00 AM to 8:00 PM.) and then only at a station or designated stop. The only exceptions which allow for unscheduled stopping, repeated throughout the small four page document, are “unless detained by obstacles in the track or to avoid collision.”

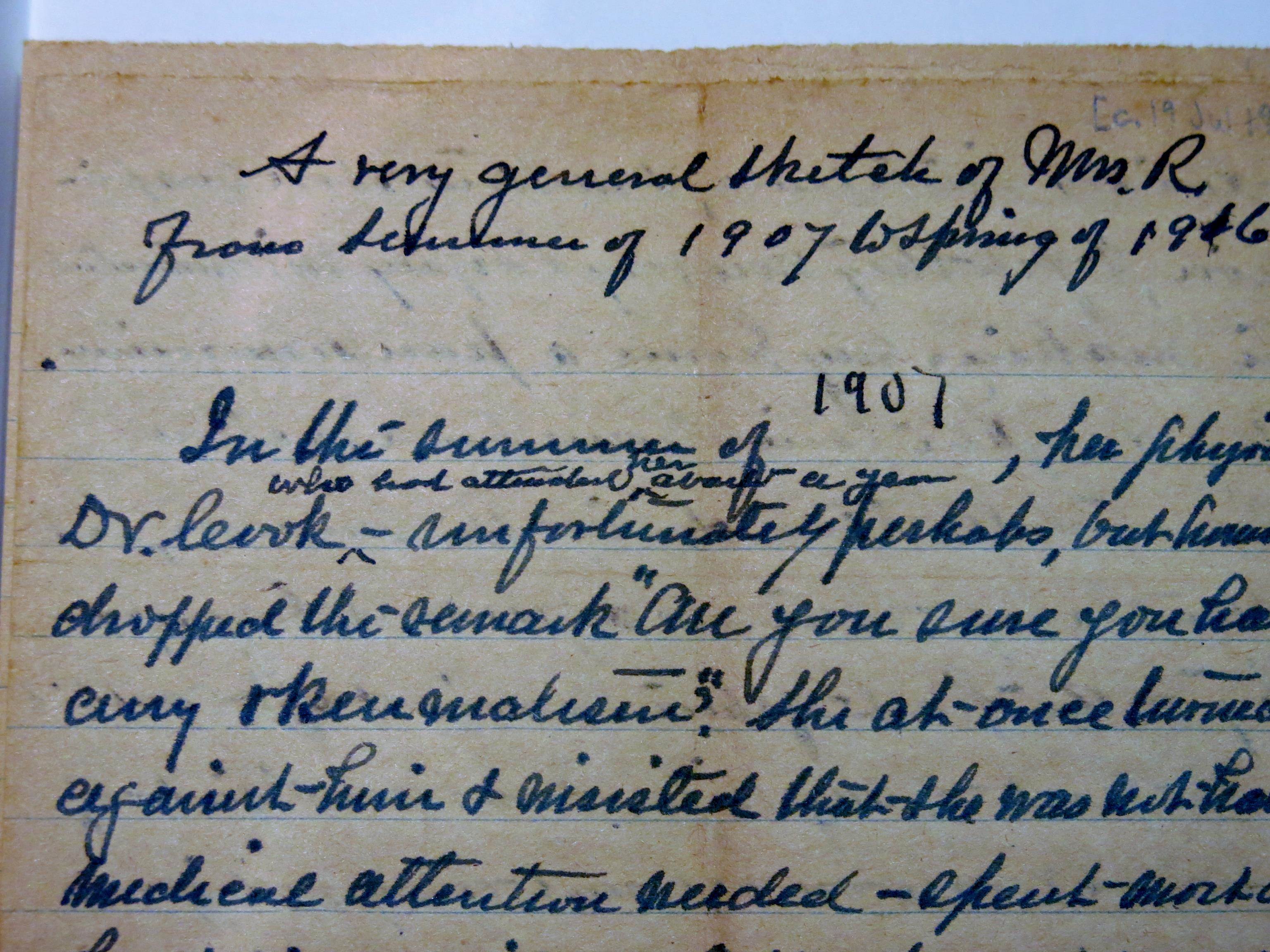

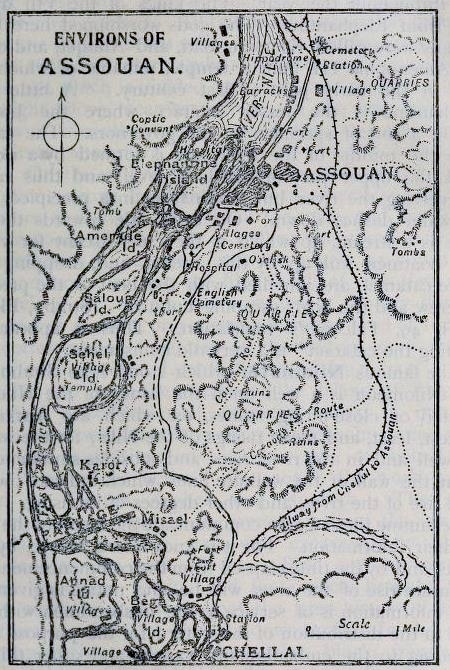

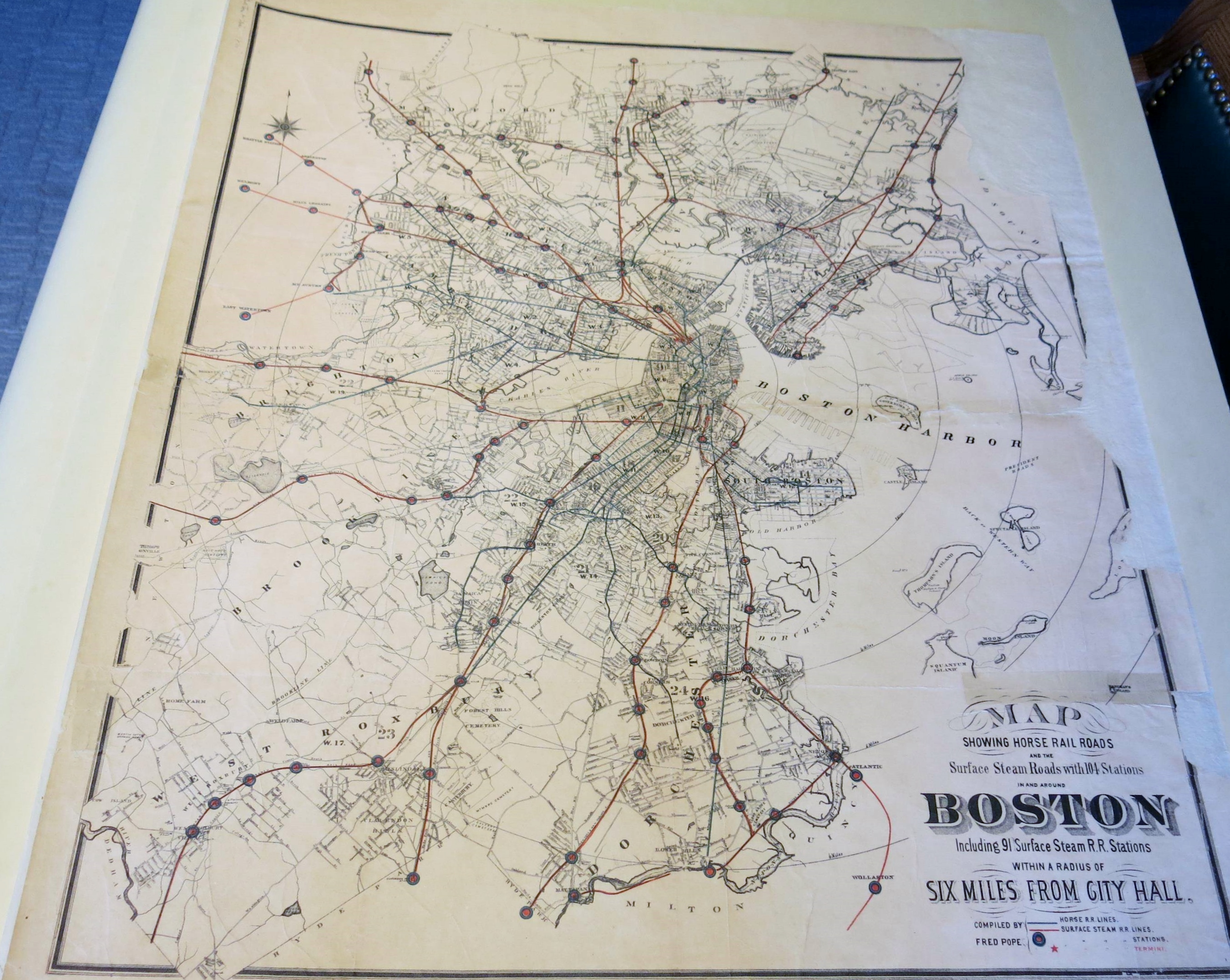

Map showing horse rail roads and the surface steam roads with 104 stations in and around Boston…1878.

(A 1876 version of this map is available online at the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.)

Yet, it was the regulations of Section 11 and 12 that proved to be the most valuable when thinking about surviving a winter with horse railroads. Section 11 spoke to the removal of snow, [] stating that if depths were sufficient “no plough shall be allowed to pass over” unless permission was granted by the Superintendent of Streets. In this case alternative methods could be employed by the railroads, in the form of sleighs, to transport citizens until rail tracks were again accessible and normal transit methods could resume.

Similarly, Section 12 discusses the use of any salt, brine or pickle or any other material employed in the melting of snow and ice would only be allowed after receiving a permit from the city. Such permits would only be given if such use would not be detrimental to vehicles crossing the tracks and rails.

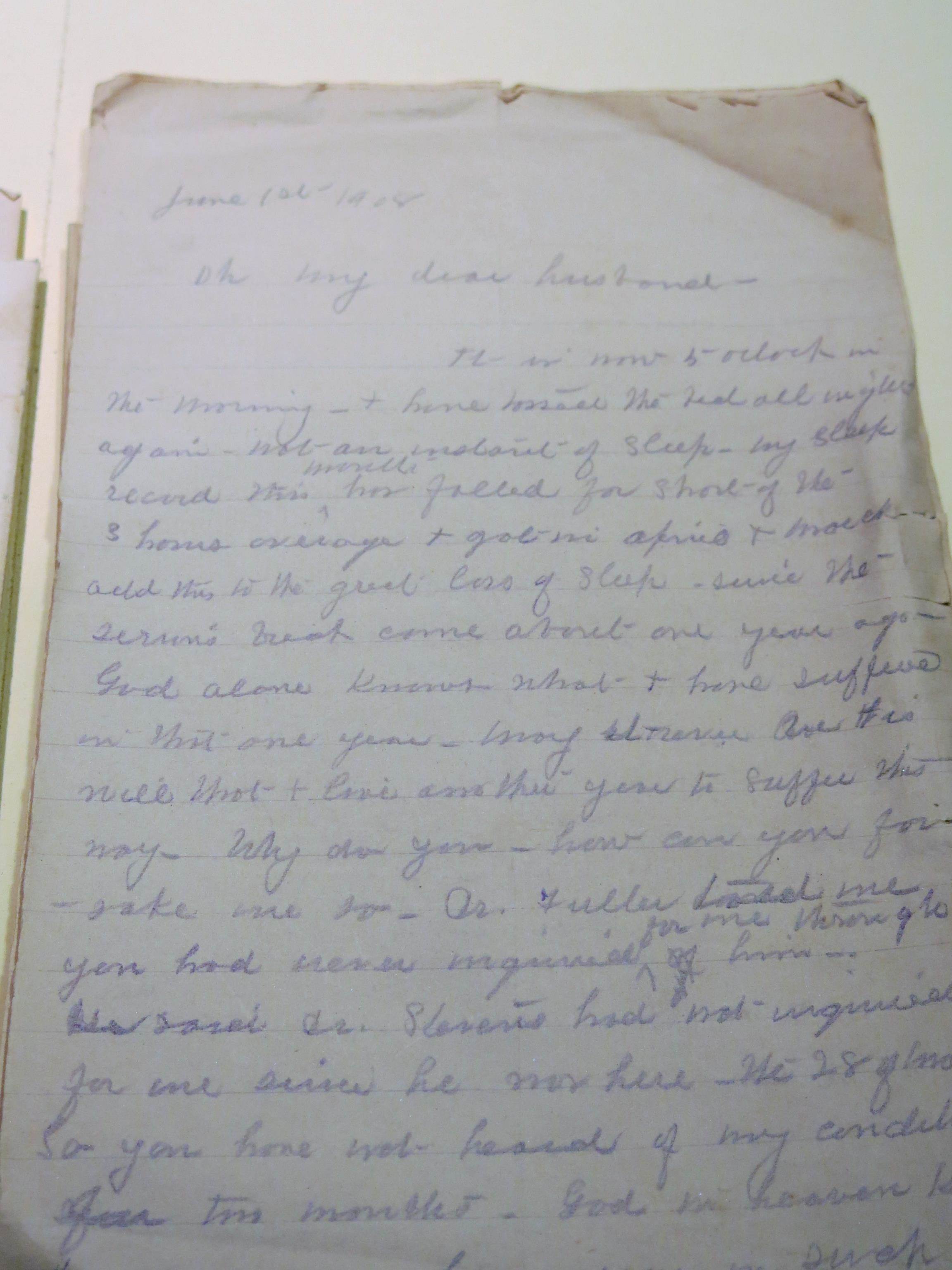

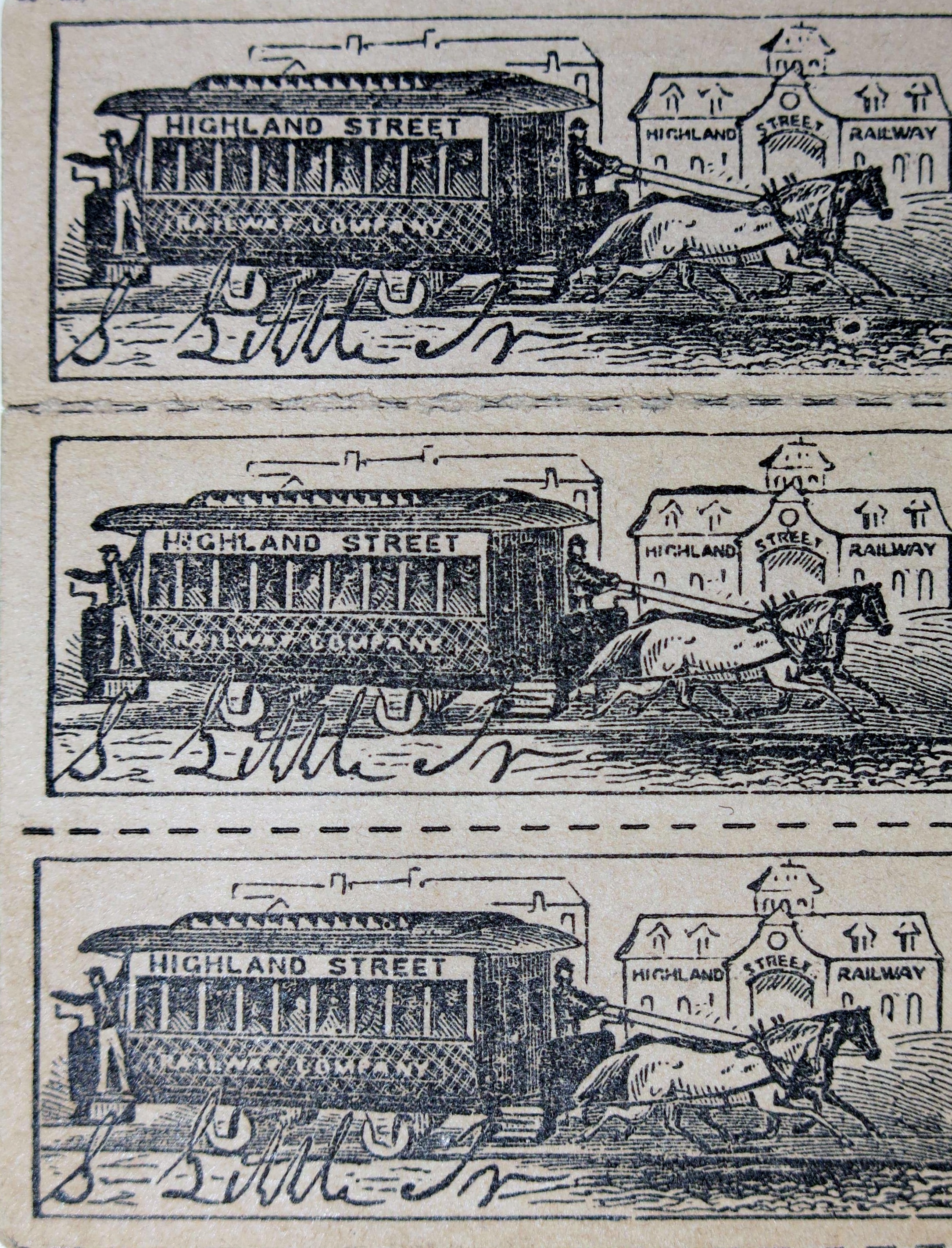

Highland Street Railroad Tickets. [No Date]

These restrictions make me imagine that if such a winter as the one last year were to have occurred during these times, the breakdown in public transit would have been far worse. While the Rules and Regulations document spoke little to the care of the working animals, the necessity of keeping the horses in working condition alone would have extended delays in transportation and confined citizens as city and transit officials worked to clear the streets.

So as we approach another winter season, and my first in Boston, a joke about returning to horse powered public transit may seem like a good idea, but I hesitate to think that the ability to combat the snowstorms of nature would be any easier won.

These are just a few samples of the material at MHS about transportation and horse railroads. If you are interested in further exploration of our collections, please visit the library or contact us for further information.