By Kittle Evenson, Reader Services

As the school year draws to a close and students across Boston slip leisurely into the summer heat, I was inspired to look at the MHS collections through a more playful lens. As difficult as it can be to piece together a historical narrative of adolescence, I wanted to see what we might have on the most playful of subjects: toys.

I found disappointingly few children’s artifacts or toys in the MHS collection. I did, however, find two items from the 19th century that brought a smile to my lips, and one or two questions to my mind.

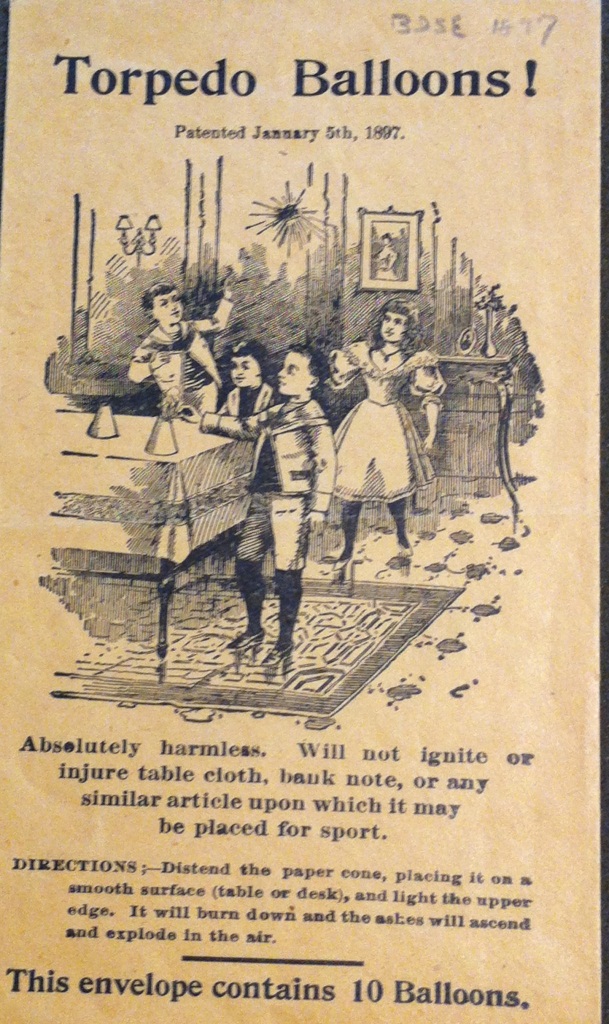

The first is a fascinating tease. An encasement for a toy dramatically named “Torpedo Balloons!”. If the name itself fails to ignite your excitement, the picture on the cover surely will. Dating to 1897, the envelop features four adolescents excitedly, yet purportedly harmlessly igniting bits of paper with a well-timed flame. Similar to fireworks, the “Balloons” are advertised to attract the budding pyrotechnic, with safety-conscious parents.

Directions: Distend the paper cone, placing it on a smooth surface (table or desk), and light the upper edge. It will burn down and the ashes will ascend and explode in the air.

As the boy in the foreground lights a “Balloon” with a match, ashes explode over his head. His unsupervised peers appear to be playing in a well-decorated formal dining room, with delicate furniture, portraits hanging in the background, and gas light fixtures on the walls. While the flying embers may enrapture the children, the advertisement reassures parents that no harm will befall their expensive possession (if not their children).

Absolutely harmless [it reads]. Will not ignite or injure table cloth, bank note, or any similar article upon which it may be placed for sport.

Though the envelope has been preserved in almost pristine condition, I was disappointed to discover that it no longer contains even a single “Balloon”.

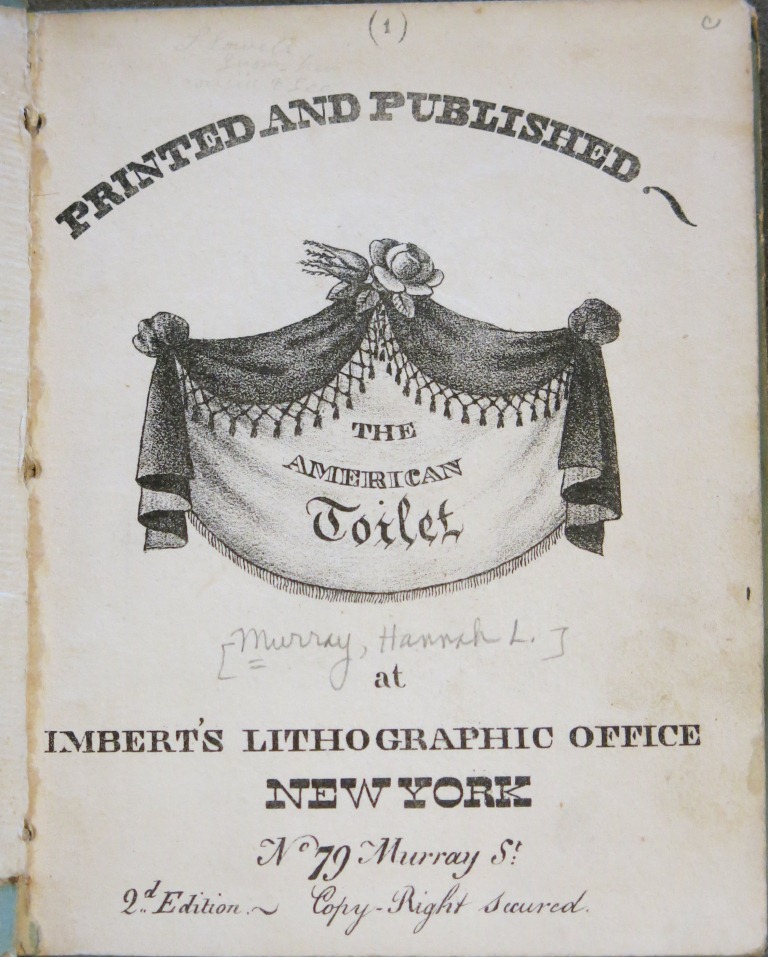

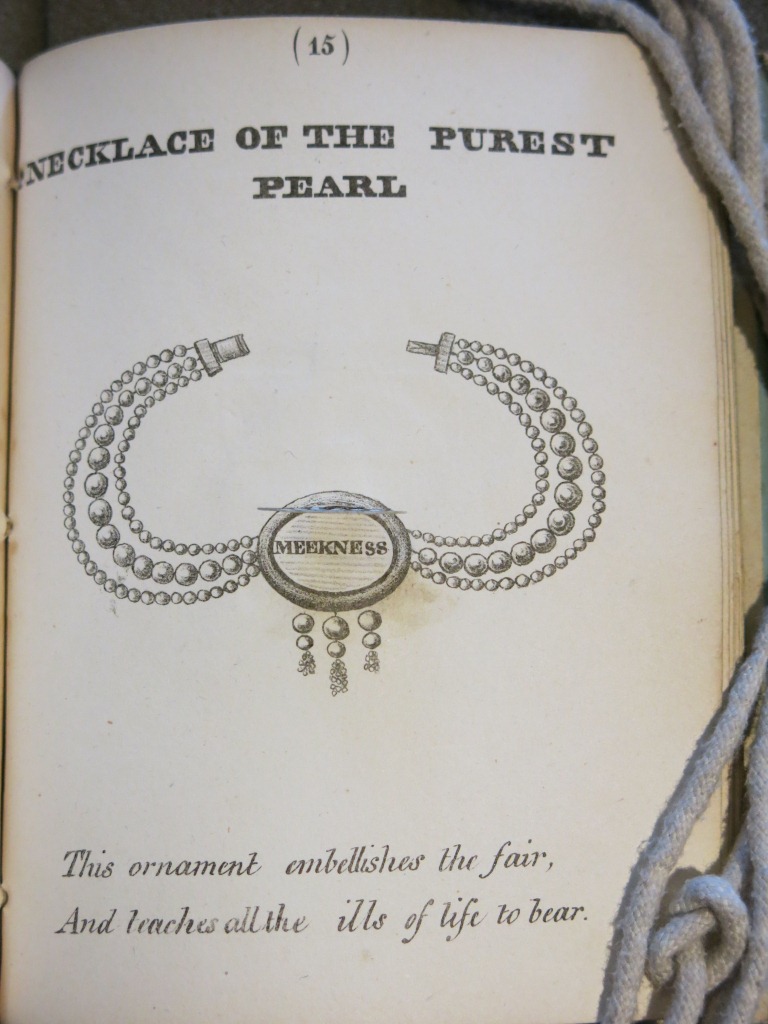

The second item I found is directed towards the girl we seen in the background of the “Torpedo Balloons!” cover image. The American Toilet, a small “conduct book” for young woman, uses emblematic illustrations to teach the reader moral precepts with regard to socially appropriate comportment and expectations.

Hannah and Mary Murry’s The American Toilet was adapted from Stacey Grimaldi’s “The Toilet,” first published in London in 1822, and includes delicate illustrations of the materials often found on a woman’s dressing table. The book is an example of a flap book, referring to the bits of paper that can be lifted to reveal hidden messages throughout the pages.

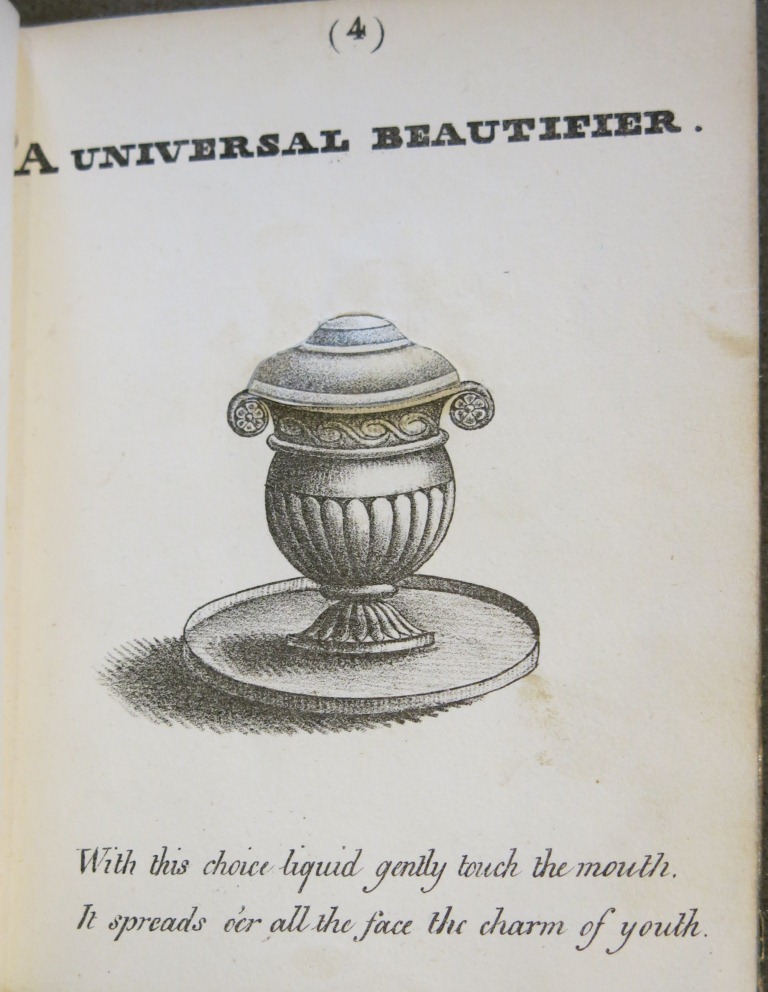

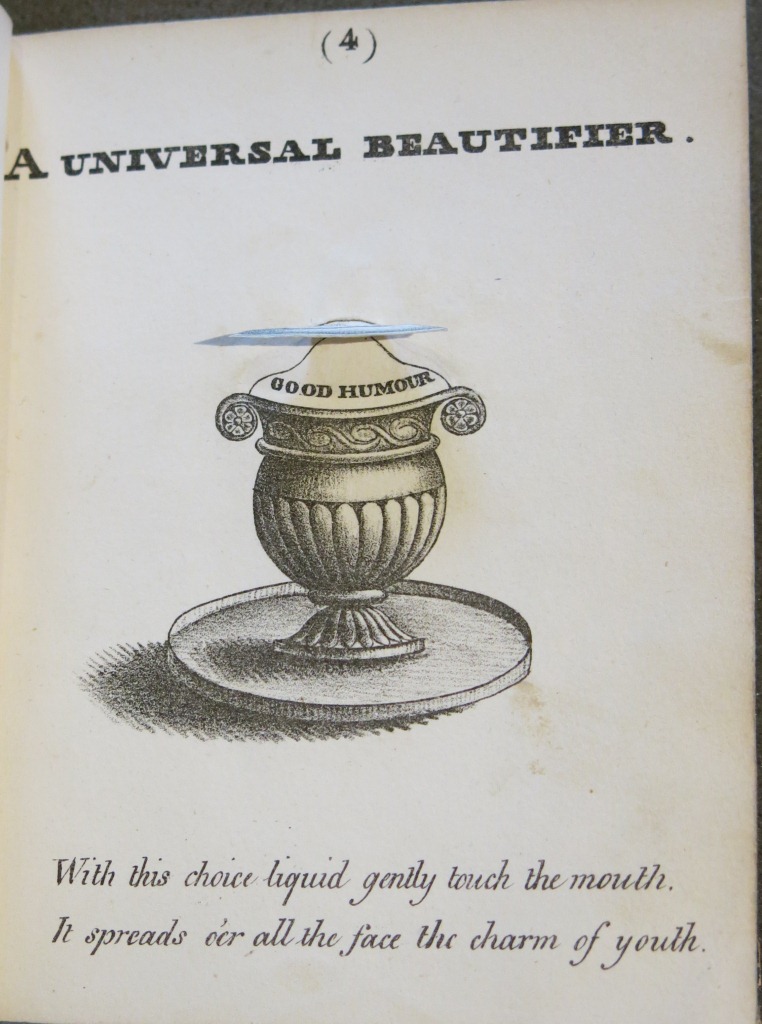

caption: With this choice liquid gently touch the mouth. It spreads o’er all the face the charm of youth

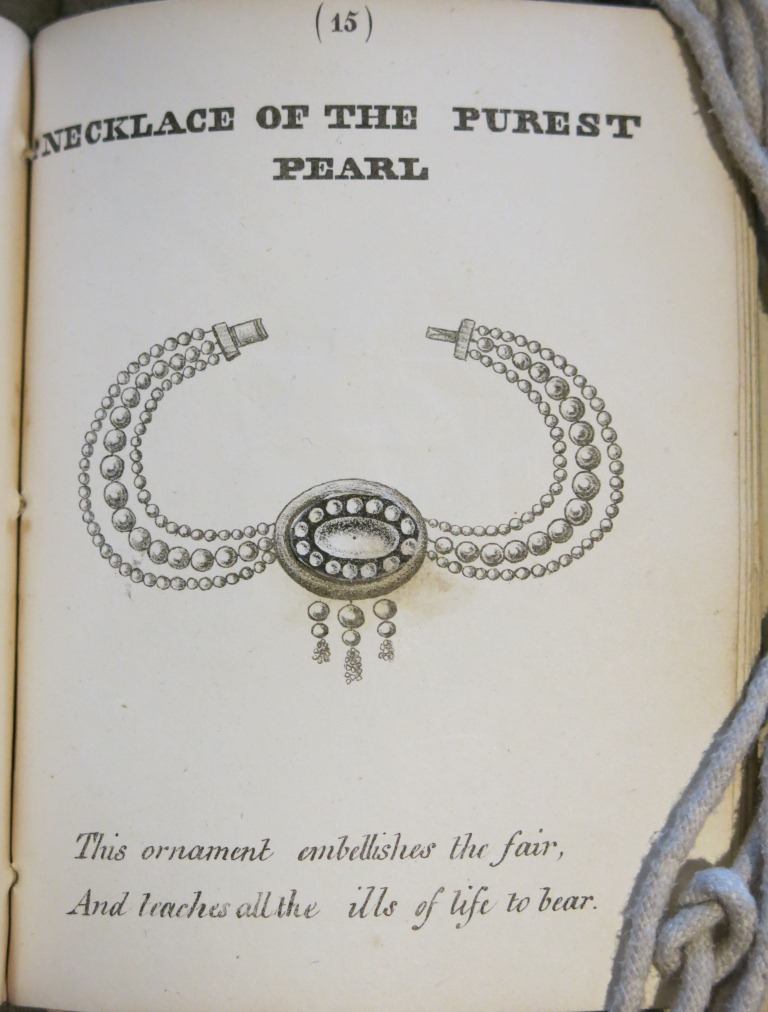

The Toilet juxtaposes shallow desires for opulent jewelry and alluring, made-up lips, with attitudes of meekness and good charm. Girls were instructed at a young age that to be socially accepted and respected they must counter desires for beauty and glamour with overt modesty and unwavering deference. The work constantly reinforcing that girls should be seen and admired as implacably pleasant creatures, not engaged with as substantive individuals.

and

and

caption: This ornament embellishes the fair, And leaches all the ills of life to bear

As engaging as the “Torpedo Balloons!” and The American Toilet are, it is important to note that they represent a very narrow experience of well cared for, educated childhood within Boston’s more affluent families. Just as adult narratives cannot be blindly generalized beyond class lines or economic boundaries; neither can children’s experiences be taken as monochrome. It is doubtful that the idyllic image of children in well-tailored clothes that adorns the “Torpedo Balloons!” packet would be mirrored in homes of less-wealthy children.

These are just a selection of our items at MHS pertaining to childhood; others include diaries and photographs that can expand our snapshot of youthful realities through personal writings, drawings, and images. If you are interested in viewing the “Torpedo Balloons,” The American Toilet, or any of our other collections in person, please contact the library or stop by for a visit.

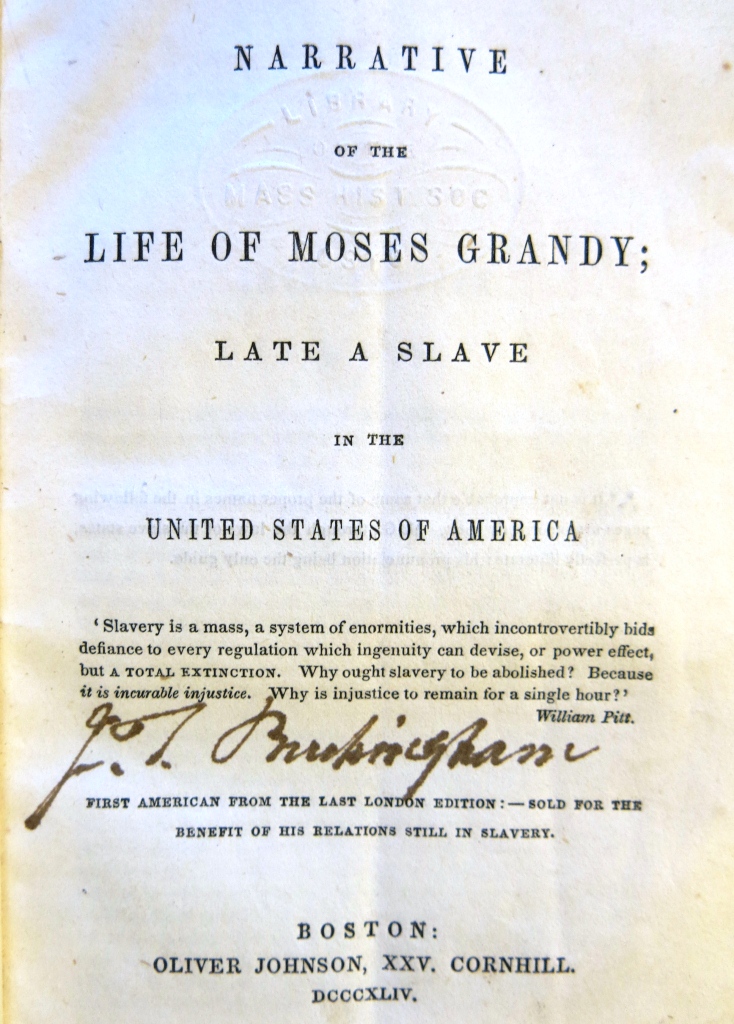

The story of Grandy’s life, written down by noted abolitionist George Thompson and first published in 1843, became popular with the abolitionist movement both in the United States and abroad. Grandy’s story, like a number of other slave narratives including those of Frederick Douglass and Solomon Northrup, served to illustrate for a wide audience the cruelties of slavery and the outrages endured by those kept in bondage. Stories of this kind helped to spread the message of abolitionism far and wide in the decades prior to the American Civil War.

The story of Grandy’s life, written down by noted abolitionist George Thompson and first published in 1843, became popular with the abolitionist movement both in the United States and abroad. Grandy’s story, like a number of other slave narratives including those of Frederick Douglass and Solomon Northrup, served to illustrate for a wide audience the cruelties of slavery and the outrages endured by those kept in bondage. Stories of this kind helped to spread the message of abolitionism far and wide in the decades prior to the American Civil War.