By Andrea Cronin, Reader Services

By Andrea Cronin, Reader Services

By Susan Martin, Collection Services

The MHS recently acquired a small volume of records of a cemetery in Holliston, Mass. that contains some fascinating information about this 19th-century town. The volume is not the original record book, which has apparently been lost, but a manuscript copy made by local historian John Mason Batchelder between 1894 and 1916. The loss of the original book makes this copy that much more significant, since it may contain records that exist nowhere else.

The North Burying Yard of Holliston, now known as the Old North Cemetery (or the Old Indian Cemetery), was established on an acre of land bought from Henry Lealand in 1801. Subscribers purchased lots for their families, and the appointed clerk, Samuel Bullard, recorded “the death and age of all persons buried in any of the Lots in said yard.” The burials listed in this volume date from 1803 to 1876. The entries are brief, but include some interesting details.

Many of the townspeople interred here are members of the Bullard, Eames, and Lealand families. Included is Civil War soldier Emerson Eames of the 22nd Mass. Regiment, who died on 22 Oct. 1862. (His remains have since been moved to the U.S. Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Home National Cemetery in Washington, D.C.) The cemetery also contains several veterans of the American Revolution, including Aaron Eames (d. 1827), Reuben Eames (d. 1818), Timothy Lealand (d. 1843), Ephraim Bigelow (d. 1834), and Aaron Pike (d. 1848). In recognition of their military service, some or all of these men received new headstones from the U.S. government in 1916, as noted by Batchelder. Pike’s story is especially poignant: he was buried as a town pauper at the age of 82 and apparently had no grave marker at all before 1916.

Also buried in the pauper section is the “child of an Irish family,” who died in 1838 at 16 months. Elsewhere we find 14-year-old Isaac Allard, a victim of typhoid fever in 1860; the unnamed baby daughter of a “single woman”; and poor James Bigelow, who “came to his death by his neckhandkerchief being caught in the turning lathe.”

Sadly but not unexpectedly, most family lots hold the remains of a husband and wife and any of their children that died young. For example, Eleazer Bullard and his wife Patty are buried with their children: Luke (10 mos.), John (3 days), Peter Parker (3 years), and Martha (4 weeks). Grown children of Eleazer and Patty were presumably buried elsewhere.

The Old North Cemetery also contains the graves of a few black residents of the town, including Jane Muguet, a state pauper and “colored girl” who died in 1846 at 16. Reuben Titus was another pauper who “lived with Wm Lovering until aged and infirm” and died at about 90 in 1855. The earliest recorded death of a black resident is that of Rose, “negrowoman of Isaac Cozzens,” in 1812.

After copying the records, Batchelder compared his book against the headstones in the cemetery, checking off the names he found there. About half of the names are not checked off, indicating burials recorded by the cemetery clerk but graves unmarked at the time of Batchelder’s visit. (These names are also missing from the Old North Cemetery name index compiled by the Holliston Historical Society in July 2011.) There are several possible explanations for this discrepancy: an error in the original record book or the transcription, a grave that was moved, or one that was never marked in the first place, such as those of the paupers. If the original volume really is lost, this copy may be the only record of the final resting places of Isaac, James, the four Bullard children, Jane, Reuben, Rose, and many others of Holliston.

By Nancy Heywood, Collection Services

What do you remember learning about the Boston Massacre? Did you learn the event took place outside the Old State House (at that time called the Town House) in Boston? Was it presented to you as a key event leading up to the American Revolution? Do you remember learning that five people (including Crispus Attucks) lost their lives? If you think of a visual image, do you think of the engraving by Paul Revere depicting townspeople being fired upon by an orderly row of British soldiers? Are you curious to explore how various primary sources describe the chaotic confrontation that took place on 5 March 1770?

It is interesting to read the words of people who were either at the scene or were able to comment on the overall atmosphere of the town after the event. Thanks to funding from the Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati, the MHS has created a new web presentation, Perspectives on the Boston Massacre, featuring letters, pamphlets, diary entries, legal notes, and engravings relating to the Boston Massacre.

Some examples of the manuscripts that are available for browsing and reading include diary entries written by merchant John Rowe who observed, “the Inhabitants are greatly enraged and not without Reason” and a letter dated 6 March 1770 by Loyalist Andrew Oliver, Jr. who wrote, “Terrible as well as strange things have happen’d in this Town.” The website also includes printed materials; some convey the Patriot perspective of the event (A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre in Boston and On the Trial of the Inhuman Murderers) and some the Loyalist view (A Fair Account of the Late Unhappy Disturbance at Boston).

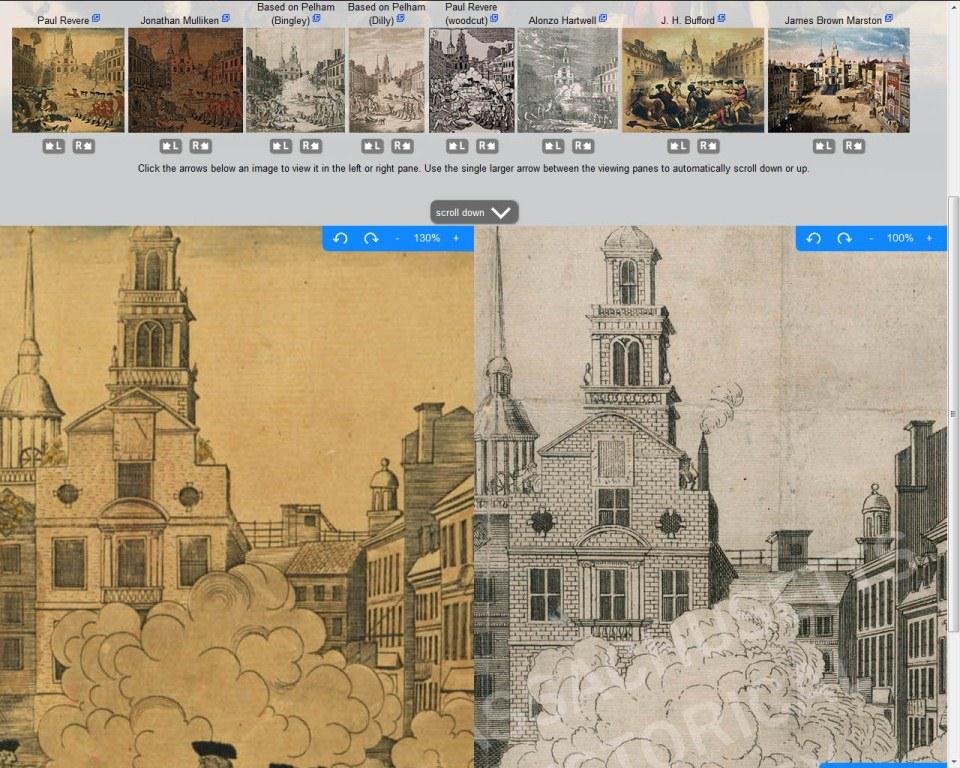

One section of the new web presentation focuses on visual representations of the Boston Massacre. Seven prints of the event, as well as one painting showing the same location in Boston in 1801, are available for close examination. Website visitors can use a comparison tool to view any two of the featured images side by side.

The website also features some selected documents relating to the two legal cases (the trial of Captain Thomas Preston and trial of the eight soldiers). John Adams served as one of the defense attorneys and the website includes page images of some of John Adams’s handwritten legal notes as well as links to the digital edition of The Legal Papers of John Adams, Volume 3, edited by L. Kinvin Wroth and Hiller B. Zobel, part of the Adams Papers Editorial Project.

The Boston Massacre was recognized as a pivotal event and supporters of the Revolutionary cause organized anniversary commemorations. The website includes published versions of orations given between 1771 and 1775 by noted figures including James Warren and John Hancock as well as a manuscript copy of an oration given by someone on the opposite side of the political spectrum who ridiculed many Patriot leaders.

Please visit www.masshist.org/features/massacre.

By Amanda A. Mathews, Adams Papers

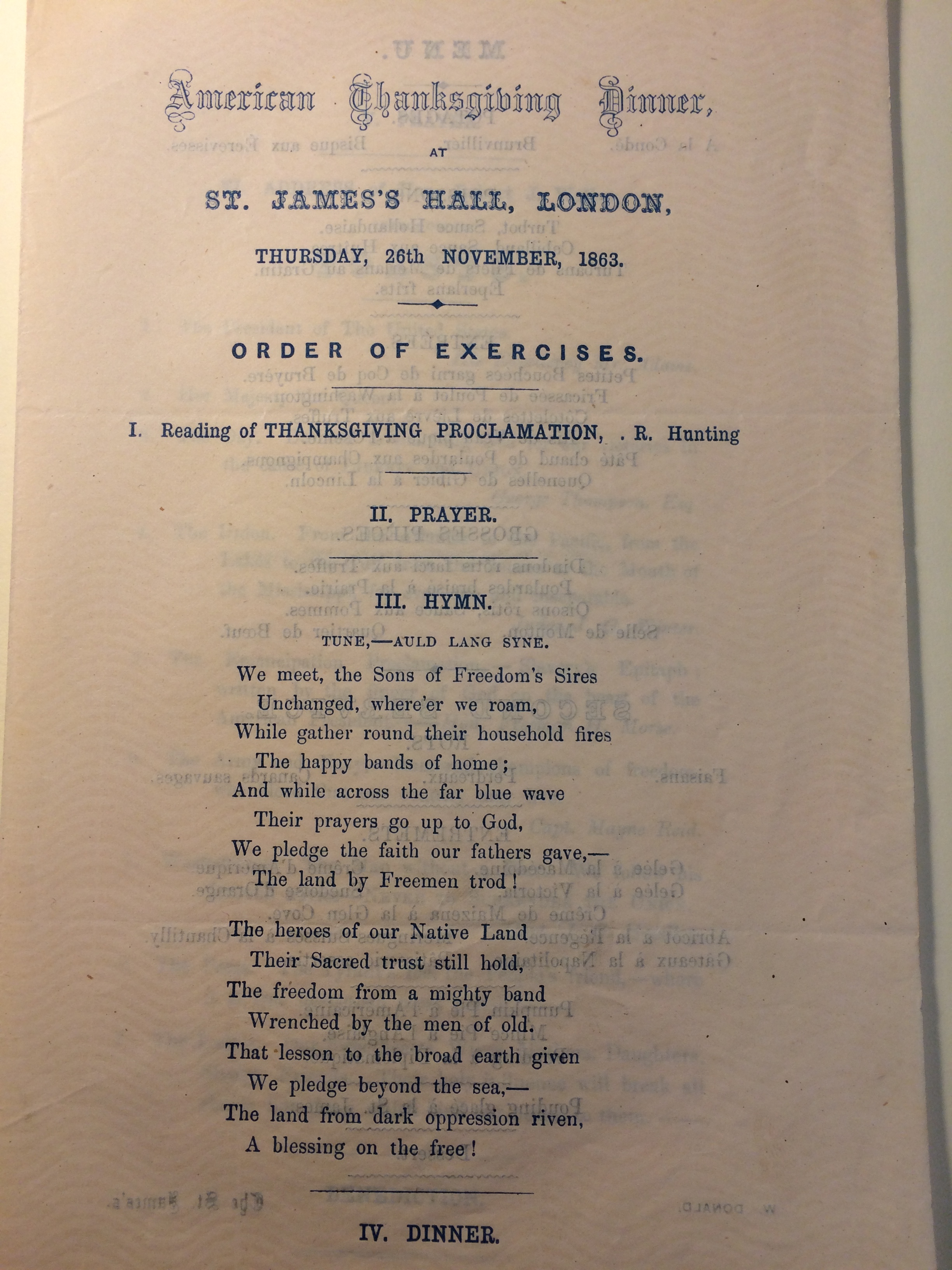

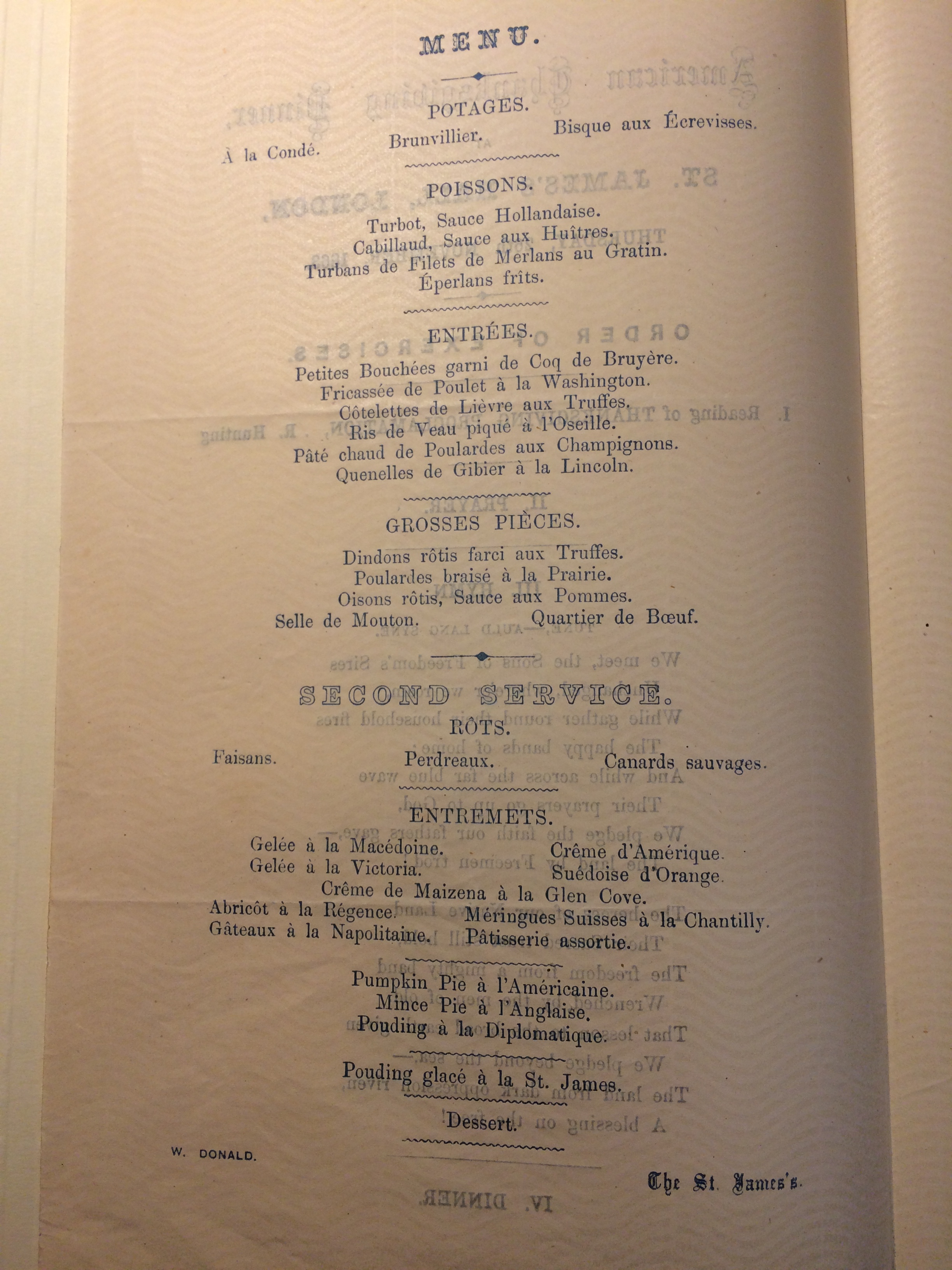

On October 3, 1789, President George Washington issued a proclamation, calling for November 26 of that year to be celebrated as a day of thanksgiving by the whole nation now independent and united under a new Constitution. Exactly 74 years later, President Abraham Lincoln, seeing the nation embroiled in a bitter, devastating, and deadly Civil War, recognized that there was still much to be grateful for as “the Most High God, who, while dealing with us in anger for our sins, hath nevertheless remembered mercy. It has seemed to me fit and proper that they should be solemnly, reverently and gratefully acknowledged as with one heart and one voice by the whole American People. I do therefore invite my fellow citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens.”

Charles Francis Adams was one of those Americans sojourning in foreign lands as the United States minister to Great Britain. Invited by a group of Americans living in London to attend a Thanksgiving Day celebration and give a toast to President Lincoln, the dinner opened with a reading of Lincoln’s proclamation. No devotee of the president, Adams noted that the proclamation was “very good, and…therefore never emanated from Mr Lincoln’s pen.” In his diary, Adams summarized his toast and feelings on the honoree:

“The press here had sneered at the notion of a thanksgiving in the midst of a desolating civil war. I thought it a good opportunity, whilst avoiding the topic of victories over our fellow countrymen which necessarily take a shade of sadness, to explain more exclusively the causes of rejoicing we had in the restoration of a healthy national solidity in the government since the announcement of the President’s term. I went over each particular in turn. The result is to give much credit to Mr Lincoln as an organizing mind, perhaps more than individually he may deserve. But with us the President as the responsible head takes the whole credit of successful efforts. It certainly looks now as if he would close his term with the honor of having raised up and confirmed the government, which at his accession had been shaken all to pieces. And this a raw, inexperienced hand has done in the face of difficulties that might well appall the most practised statesman! What a curious thing is History! The real men in this struggle have been Messr [William] Seward and [Salmon] Chase. Yet the will of the President has not been without its effect even though not always judiciously exerted.”

Shown here is the program for that Thanksgiving Day celebration. Since 1863, Americans around the world have stopped in late November each year for a day of joy and thanksgiving with friends and family, as we will tomorrow. Wishing you and yours a Happy Thanksgiving!

By Anna J. Clutterbuck-Cook, Reader Services

In late October of 1915, as the days in New England grew shorter and the temperatures colder, twenty-seven-year-old Mildred Cox Howes of Brookline, Massachusetts, boarded a train with her husband, Osborne “Howsie” Howes, and headed west. Between 22 October and 14 November 1915 the couple traveled to California, where they attended the Panama-California Exposition in San Diego and the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. As was her habit, Mildred carried with her a line-a-day diary in which she recorded their movements, travel times, meals, friends met along the way, and sights seen.

Despite the fact that Mildred had recorded in early October spending time rolling bandages at a local hospital, presumably to be sent overseas, her own life was largely untouched by the reality of war in Europe. While England and the continent were digging in for the war to end all wars, the United States was in an expansionist, celebratory mood. Having recently flexed its imperialist muscles in the Spanish-American and Philippine-American wars (1898-1903), in 1914 the United States finally saw the completion of the Panama Canal (1903-1914) which dramatically increased the speed of an ocean voyage from the Atlantic to Pacific coasts of North America, saving ships nearly eight thousand miles of travel around Cape Horn. The Panama-California and Panama-Pacific International expositions were a message to the world regarding the United State’s new place on the world stage, as well as an opportunity for San Francisco, particularly, to celebrate its reconstruction following the devastating 1906 earthquake.

Mildred’s diary is spare, but does provide readers with a sense of the nature of upper-middle-class travel during the early twentieth century, before widespread adoption of the automobile. The Howes left Brookline on Tuesday, 22 October by the 12:34 train for Chicago. Mildred reported a “very pretty” ride through the Berkshires. Arriving in Chicago the following morning, they spent the day in Chicago visiting friends, dining out, and attending a garden show that Mildred described as “not much good.” Departing on an evening train, the Howes passed through Kansas and New Mexico, reaching the Grand Canyon a week after leaving home.

The Grand Canyon was not yet a national park (it would be dedicated in 1919), but nonetheless a popular tourist attraction. “About 10- we started & walked down to the plateau 5 miles & very steep,” Mildred wrote, “A guide & mule met us there …I rode up. Howsie walked. Fine. Wonderful views.”

The Howes reached San Diego the following day, after a morning spent traveling by train across the desert to Los Angeles, and then changing trains for the trip south to San Diego. They spent three days in San Diego, sunbathing at Coronado Beach, visiting the Panama-California Exposition, and driving down to Tijuana for a day (“Most amusing & just like a book”).

Departing from Coronado Beach by motorcar, the couple drove through Murietta Springs, Riverside, Pasadena, Los Angeles, arriving in Santa Barbara on Monday, November 1st. The automobile appears to have been as much for pleasure as transport, as Mildred repeatedly describes having “motored around” the cities they pass through, including a detour up to the top of Mt. Rubidoux, today a city park. Mildred also lists the names of the hotels at which the couple stay, often luxurious locations such as the Mission Inn (Riverside) and the Potter Hotel (Santa Barbara). When they arrive by train in San Francisco, they take up residence at the newly-constructed Palace Hotel, about three miles from the exposition — located between the Presidio and Fort Mason in what is today the Marina District.

“First [day] at the exposition – cleared off into a lovely day,” Mildred reported on November 4th. “Saw the manufactural palace & fibral arts… Dined at the hotel & went out again. Took a chair & looked at the illumination & listened to the bands.” Mildred and Howsie remained in San Francisco for a week, taking in the exposition and exploring the area. On exposition days, they arrived mid-morning and stayed until dinner, sometimes returning in the evening. On Saturday, Mildred reported going to the cinema to see “On Trial” (“very good & exciting”); on Sunday they took a Packard car and drove to Palo Alto for lunch with friends. On Tuesday they went to see Houdini perform at the Orpheum.

Twenty days after leaving Boston, Mildred and Howsie packed and, after a final morning at the fair, left at 4 o’clock on an eastbound train, traveling through Nevada to Ogden, Utah, and on across Wyoming and Nebraska at a brisk pace; they reached Chicago after three days’ steady travel, stopping the day to visit the art museum and stretch their legs. Boarding the train in Chicago they discovered friends Jessie and Frank Hallowell, and John Balcheder, also headed for Boston. By Sunday, November 14th, they were home once more.

Briefly factual in tone, Mildred’s diaries reveal only glimpses of her subjective experiences as a traveler, but nonetheless strongly evoke the rhythms of early-twentieth century travel for modern readers. If you are interested in this, and other diaries, kept by Mildred Cox Howes, you are welcome to visit or contact our library to access the collection.

**Photographs from Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. Photograph Collection: Grand Canyon of the Colorado (#183.2043); Lotta’s fountain in front of the New Palace Hotel (#183.2022); Crowds at the Golden Gate Park (#183.2027).

By Thomas Lester, Reader Services

During the French and Indian War (1754-1763), the fortified French city of Louisbourg loomed over the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, denying the British access to the Saint Lawrence River – the route to capturing the key cities of Quebec and Montreal. The fortress, considered the “Gibraltar of the North,” had famously been captured by a combination of New England militia and the British navy in 1745, only for the Treaty of Aix-La-Chapelle to return it to the French in 1748. Now, a decade later, the invading British forces looked to capture the fortress for a second time.

In early June 1758, ground forces under the command of Jeffery Amherst landed outside the city and began a siege operation which, in accordance with the standard of 18th century siege warfare, meant digging a network of trenches surrounding the city.

While Amherst’s command toiled in the trenches, the British navy remained concerned about French ships defending the harbor. Though only five French ships of the line remained by late July, they proved enough of a menace to receive considerable attention by way of British artillery fire. As a result, on July 21st, a cannonball penetrated one of the ships, detonating its powder magazine. The ensuing blaze was so hot that it set fire to the sails of two neighboring ships, burning all three down to the waterline.

Three days later, on July 24th, Admiral Edward Boscawen, commander of all British vessels in North America, informed Amherst of his bold plan to capture the remaining two ships – the Prudent (74 guns) and the Bienfaisant (64 guns) . Late in the night of July 25th-26th, two squadrons under the command of Captains John Laforey and George Balfour, totaling approximately 600 sailors and marines, rowed into the harbor. Concealed by the dark and fog, and with Amherst ordering his artillery to “fire into the works as much as possible, to keep the enemy’s attention to the land,” the two squadrons slipped past the French battery guarding the entrance to the harbor and approached the two French vessels undetected.

As Laforey’s command approached the Prudent and Captain Balfour the Bienfaisant, each was hailed by sentries aboard the ships. Receiving no response, the guards opened fire, breaking the silence. The squadrons then moved quickly to maneuver alongside their respective targets, capturing both ships with minimal resistance, but at a cost of sixteen casualties (7 killed, 9 wounded).

Hearing the events that transpired, the French defenders were alerted to the threat and opened fire upon the two ships. Under fire, and finding the Prudent run aground, the British sailors set her ablaze. The Bienfaisant, meanwhile, was towed to the Northeast corner of the harbor, safe from French artillery fire. The image above, printed in 1771, depicts the Prudent caught in a blaze, while nearby the Bienfaisant is towed to safety.

The following day, with Amherst’s ground forces making ready to breach the city walls and Boscawen’s fleet entering the harbor, the French governor sent a messenger to Amherst initiating the surrender of the city.

Discussing the siege, historian Julian Gwyn notes in his book, Frigates and Foremasts, that “some naval and military historians have asserted that once the British assault landing force had succeeded, the capture of the fortress with its garrison was a foregone certainty. Yet none of the British or French accounts expressed this view.” He goes on to comment that “the loss of these two warships had a profound effect on the French defenders…morale plummeted within the town, and the fatigue occasioned by the siege, which until then had been borne without complain, suddenly became unendurable for many.”

In the aftermath of these events, Captain Balfour was awarded with command of the Bienfaisant, and command of the frigate Echo to Captain Laforey. Their lieutenants were also awarded with new commands of their own.

In the short-term, the event depicted was significant for breaking French morale and contributing to the success of the siege. In the long-term it opened the heart of New France, most notably the cities of Quebec and Montreal, to British invasion via the Saint Lawrence River. Having previously read about the events that transpired, I was pleasantly surprised when I stumbled upon this print in our collection. I love the color of the raging fire engulfing the Prudent set against the dark, foggy night with Louisbourg in the background. Most of all I was caught in the suspense while reading about this risky operation.

This print was originally a painting by Richard Paton (1717-1791). Born in London in 1717, Paton was found as a poor boy living on the streets by an admiral of the British navy and went to sea. Receiving no professional training as an artist, Paton is known for depicting the famous sea-battles that occurred during his lifetime. His paintings were exhibited it the Royal Academy of Art in London from 1776-1780.

The engraving was made by Pierre Charles Canot (ca. 1710-1777). Born in France, he moved to England in 1740 where he spent his professional career as an engraver. Most famous for his engravings of Paton’s works, in 1770 he was elected Associate-Engraver of the Royal Academy of Arts in London.

By Peter K. Steinberg, Collection Services

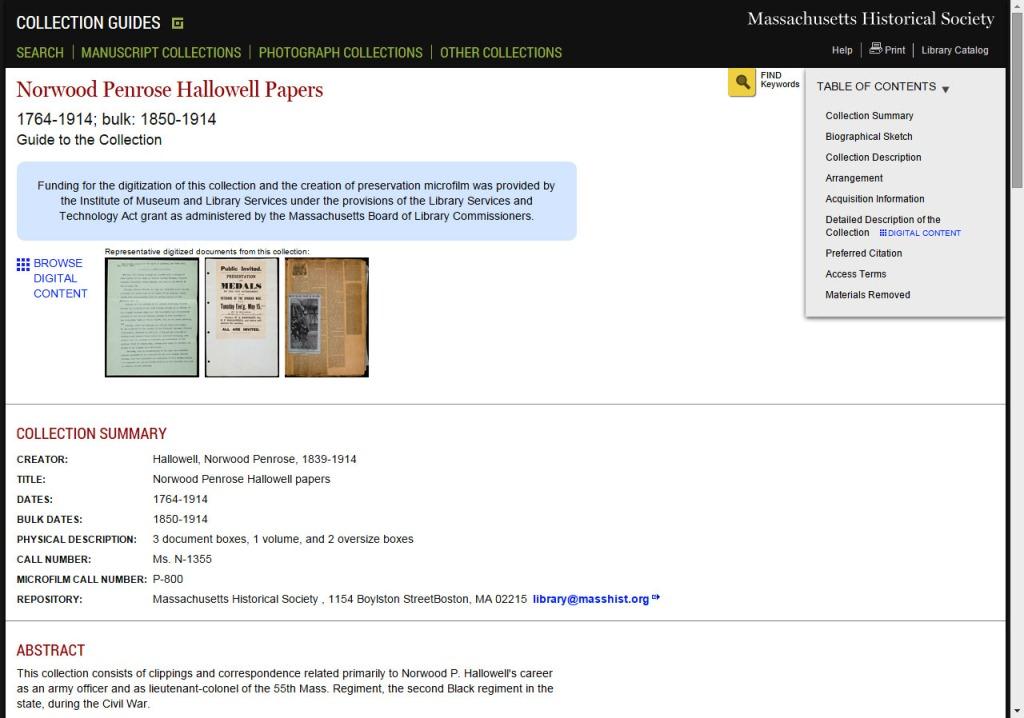

The recently launched fully digitized manuscript collections of Civil War papers at Massachusetts Historical Society (MHS) is a significant step forward in making our collections accessible remotely. Motivated by the sesquicentennial of the Civil War, the presentation of full-color surrogates of complete collections will be a model for further digital projects at the MHS. Just as the MHS was inspired by the fully digitized collections available on other websites, we hope our approach can be useful as other organizations undertake similar projects.

Many of the collections were straightforward to digitize. Crudely and in short: remove a folder from the box>remove a piece of paper from the folder>scan>repeat. Of course, much more goes into the process than that: determining permanent and secure storage for 9,000+ images, repairing documents in need of some T.L.C. (Tender Loving Conservation), potentially informing researchers they cannot work with the materials for a while, capturing metadata, tracking all the moving pieces, and so much more. Some collections contained material separated for specific reasons. Photographs and oversize materials, for example, are stored in different locations as these items have their own preservation requirements.

The Norwood Penrose Hallowell papers proved to be particularly challenging to digitize for a variety of reasons. There are loose papers; three disbound scrapbooks; an oversize, intact scrapbook; an oversize scrapbook volume; and some of those aforementioned separated oversize materials. Funding for the digitization of the nine Civil War manuscript collections that enabled both the creation of preservation microfilm and the online version of the collections was provided by the Institute of Museum and Library Services under the provisions of the Library Services and Technology Act grant as administered by the Massachusetts Board of Library Commissioners. Part of the budget of the grant enabled us to send large (oversize) materials to the Northeast Document Conservation Center in Andover for imaging. As part of the preparation to send the collection out, we needed to record how many pages there were in total and how many digital images we expected. Then, once we got the collection back, we needed to reconcile that the collection was returned complete and that all of the anticipated digital images were made.

The oversize scrapbook, a.k.a. Scrapbook Vol. 3 was the most difficult part of this collection to represent online. It contains pasted-down newspaper articles, photographs, tipped-in items, photocopies, letters, pamphlets, and other relevant memorabilia. By browsing the digital images, you will see a number beneath each thumbnail image in the sidebar on the left. This is the sequence number that we used to order images so that they will accurately reflect the order of the original item. On occasion, the thumbnail images will appear to be the same. But, please do not be fooled or think us careless. What is actually happening is that a more complicated scrapbook page—one containing something with print on both side of the leaf, or a multi-page document—is being imaged page-by-page, with items flipped up, down, or over, or with loosely tipped-in pieces being photographed and removed one by one.

A good example of this is the sequence number range of 71-76. In sequence number 71, you can see the page in its static, flat form, as it would appear if the volume were in front of you: a letter (of six pages) and a drawing an animal (a doe? a deer? a horse? – I know metadata, not animal species). Sequence 72 shows the first page of the letter flipped up, so that you can read the second page, sequence 73 shows the third page of the letter, and so on. This sort of thing happens throughout the series (see also, for example, sequence numbers 140 -148; and 149 -157, which culminates fascinatingly with the story of death of “Jo-Jo” the “Dog-Faced Man”). We hope that this blog helps to explain the treats this collection has to offer. Happy Hallowell!

By Andrea Cronin, Reader Services

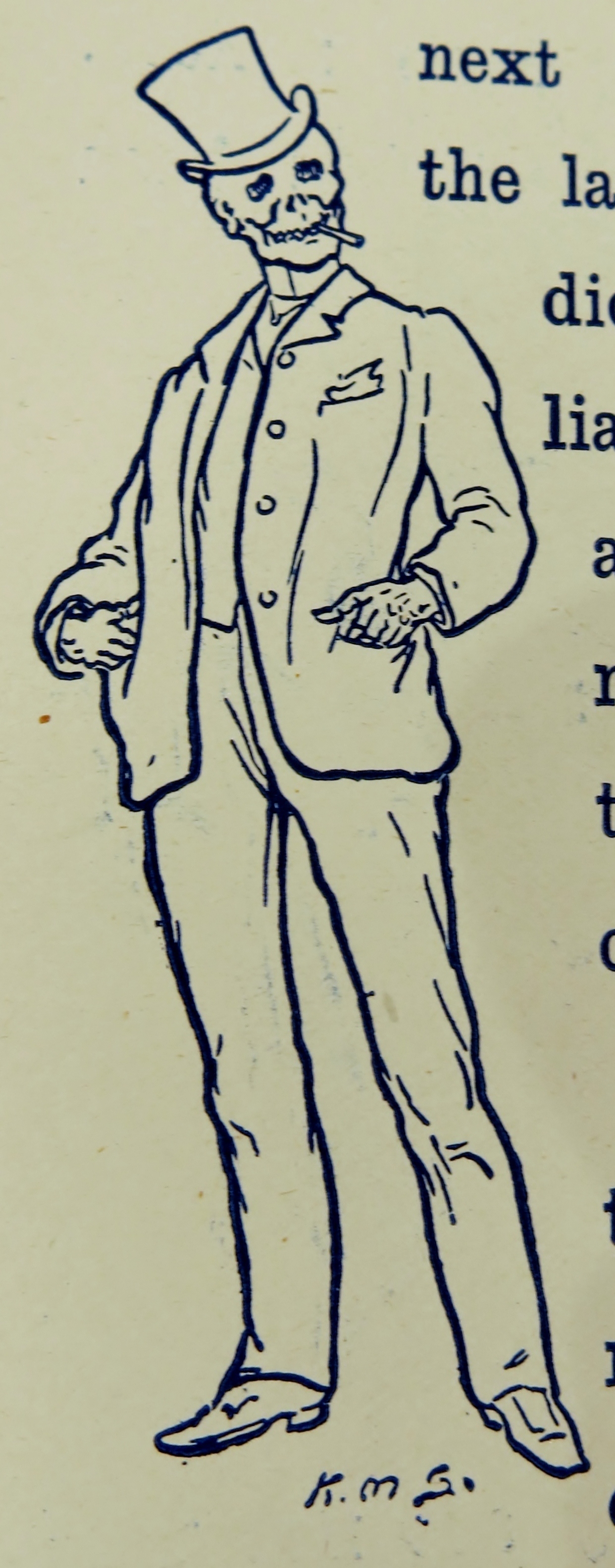

Happy Halloween, dear readers! In preparation for all the spooky fun and candy this evening, I present you with two “facts” about ghosts from English humorist Jerome K. Jerome’s 1891 book, Told After Supper:

1. It is always Christmas Eve in a ghost story.

1. It is always Christmas Eve in a ghost story.

Jerome K. Jerome begins his introduction with the following:

It was Christmas Eve. I begin this way because it is the proper, orthodox, respectable way to begin, and I have been brought up in a proper, orthodox, respectable way, and taught to always do the proper, orthodox, respectable thing ; and the habit clings to me.

Of course, as a mere matter of information it is quite unnecessary to mention the date at all. The experienced reader knows it was Christmas Eve, without my telling him. It always is Christmas Eve, in a ghost story.

Christmas Eve is the ghosts’ great gala night. On Christmas Eve they hold their annual fete. On Christmas Eve everybody in Ghostland who is anybody – or rather, speaking of ghosts, one should say, I suppose, every nobody who is any nobody – comes out to show himself or herself, to see and to be seen, to promenade about display their winding-sheets and grave-clothes to each other, to criticize one another’s style, and sneer at one another’s complexion.

If Jerome is to be believed, you may rest assured that you will most likely not see a “real” ghost on Halloween. If you do see a ghost, you can talk about the contrary occurrence to Jerome’s ghost on Christmas Eve. The English writer’s ashes are buried at St. Mary’s Church, Ewelme, Oxfordshire, England.

2. The act of homicide results in both murderer and murdered ghosts.

The Tales After Supper narrator relates the following story: A mysterious young woman in a nightgown visits the room of a young man staying in his family county house for the Christmas holiday. She sits on his bed before suddenly vanishing. The young man interrogates the ladies of the house the next morning in hopes that he may identify the visitor.

[The host] explains to [the guest] that what he saw was the ghost of a lady who had been murdered in that very bed, or who had murdered somebody else there – it does not really matter which: you can be a ghost by murdering somebody else or by being murdered yourself, whichever you prefer. The murdere[r] ghost is, perhaps, the more popular ; but, on the other hand, you can frighten people better if you are the murdered one, because then you can show your wounds and do groans.”

If given the choice, I would prefer to not become a ghost any time soon. Happy Halloween to everyone and to all, a sweet night!

By Susan Martin, Collection Services

Today we commemorate the 85th anniversary of Black Tuesday, the worst day of the 1929 stock market crash that preceded the Great Depression. For a close-up look at these events, we turn to the papers of Henry P. Binney (1863-1940), a Boston banker and investment adviser. His voluminous outgoing correspondence, bound into 14 large letterbooks and covering the last thirty years of his life, forms part of the Henry P. Binney family papers.

The Wall Street crash began a few days before, 24 October 1929, on what came to be called Black Thursday. The bull market sustained through most of the 1920s had culminated in a record-high Dow Jones Industrial Average at the beginning of September 1929 before stock values started to tumble. Black Thursday saw the first precipitous drop. Nearly 13 million shares were traded in a single day, double the previous record and more than triple the volume of an average day. The boom was over. On that day, Binney wrote to a colleague who had proposed an investment opportunity:

On my return from a short trip to New York I find your letter of October 21st. While I do not know what reaction Mr. Ray Morris would now have regarding your proposition if presented to him I do not believe he or anybody else would consider anything new at this time. The tremendous shake-out of this morning in the stock market has taken the gimp out of pretty much everybody and it will take time for the panic of today to be forgotten. During the last week paper profits have faded away and many people rich at the beginning of said period are now poor.

To another investor on the same day, he wrote, “Everybody is pessimistic about everything just now.” Little did he know that Black Thursday would be followed by an even more frightening plunge in the market. On Black Tuesday, 29 October 1929, 16.4 million shares were traded in an all-out panic. While these numbers pale in comparison to the trading that we see on Wall Street today, they were unprecedented at the time. The stock ticker couldn’t keep up and ran hours behind as the market spiraled out of control.

One of Binney’s frequent correspondents during this period was his brother-in-law Roy E. Sturtevant. A week after the crash, he told Sturtevant:

Even the man who had his nose close to the grindstone on those fateful days did not, apparently, benefit much….Personally I don’t like the outlook. Such a tremendous crash as has occurred will take long to live down.

Binney’s prediction was prescient. He knew it would take years for the stock market to recover, but he did his best to stay optimistic and often reassured his friends and colleagues. On 30 January 1930, he joked to Sturtevant, who served as vice-president and treasurer of the Ludowici-Celadon Co. in Chicago:

I have just been reading your circular letter of January 28th to the stockholders, and have been looking over your figures for 1929. I imagine this is the first time the “Profit for the year” has been in red! However, lots of Industrials are on the same raft with you, so don’t be depressed.

Binney himself seems to have been less dramatically affected by the crash, at least initially, than many others. He was already a fairly conservative investor, preferring the safer bond market to risky stocks, and the events of October 1929 strengthened that tendency.

That’s not to say he didn’t feel the pinch. Between 1929 and 1932, the Dow Jones would lose about 90% of its value, bottoming out in July 1932. Curious to see how Binney was holding up, I looked ahead to his correspondence of that year. His letters had become more pessimistic and skeptical. I found him writing often about cutting back on utilities and luxuries, such as a proposed trip to Europe for his 18-year-old daughter Polly. He even swallowed his pride and accepted a gift from his brother- and sister-in-law, the Sturtevants:

Between ourselves, we will have to see how the depression works out. If matters remain as they are, it would be better in my judgment not to spend the money, especially as Europe is not a real necessity. I try not to be too gloomy when at home but, notwithstanding my efforts, both of my ladies have come to the conclusion that I had better hoard gold for contingencies. This being the case, I have decided to accept, with a million thanks, the check….No people I have ever known have ever been half as nice as you and Roy have been to us.

Unsurprisingly, his correspondence had also become more overtly political. He preferred Herbert Hoover to Franklin D. Roosevelt, but felt Hoover wasn’t up to the job. Binney feared a revolution if the Depression dragged on much longer. The relief measures he supported included a $5 billion bond issue to put people back to work, the repeal of Prohibition for additional revenue, and a tax on all manufactures. Here’s a sampling of his more political letters:

Needless to say I am dreadfully sorry to hear that you are so blue – it is quite the fashion here. However, things must turn or the U.S.A. will be faced by a Revolution before snow flies! I have no use for Mr. Hoover but even he may be better than whoever the Democrats nominate! Two or three days ago in New York I found rather a more cheerful tone although when one man laughed most of us fainted away at the unusual sound! [17 June 1932]

Lots of people think The Great Depression is on its last legs but, having turned pessimist, I am not at all certain of this. Apparently President Hoover will not be returned. I do not know a single Republican who will vote for him. The G.O.P. gentlemen all have their tails between their legs and either won’t vote at all or cast their votes for Roosevelt who nobody likes but, it is thought, cannot be as sloppy as H.H.! [13 July 1932]

The Depression seems to be passing, at least stock-marketwise. You had better print in your well[-]known newspaper that the one reason for this is the action of the Government in seriously attempting to put people to work. The method adapted is a little clumsy but what can one expect of Washington?! [9 Aug. 1932]

By Olivia Mandica-Hart, Library Assistant

Like many New Englanders, I followed the recent Market Basket labor strike with near-obsessive interest. Of course, a small, selfish part of me was irked that my “More for Your Dollar” shopping had been temporarily suspended. But beyond that, I was inspired by the employees’ bravery and revolutionary spirit. After weeks of negotiations and uncertainty, I was pleasantly surprised that the workers had triumphed over the CEOs. I’d noticed two important things while following the story; first, that many of the employees who were protesting “on the front lines,” as well as the consumer advocates who boycotted the store, were women. And secondly, that in the news media, many labor activists discussed the “record breaking” strike as distinctly unique to Massachusetts. These two facts are not particularly startling, given the state’s strong history of labor organizing and activism, much of which began with Massachusetts women.

In the 1830s, more than fifty years before labor movements became popular throughout the United States, the Lowell Mill women began organizing and striking, forming the first union of female workers in the United States. Over the next few decades, the same radical spirit picked up momentum and moved to the city of Boston.

In 1874, forty-six years before the 19th Amendment granted women the right to vote, a group of female business owners in Boston formed the Business Woman’s Mutual Benefit Association, which published circulars in Boston newspapers to advertise its services.

This circular, dated 27 February 1874, explains that “the object of [the] association [was] threefold:”

1st. To provide a fund from which a certain sum shall be paid to any member in case of sickness.

2nd. To provide a fund from which members in case of extreme need can obtain small loans, without interest, said loans to be returned by installments, in such sums and at such rates as shall be agreed upon.

3d. To provide respectable burial to deceased members.

To include as many people as possible, the Association established two tiers of membership: beneficiary members paid yearly dues and were subsequently entitled to all of the aforementioned benefits. Honorary members paid a one-time fee and received a certificate, but did not gain any benefits from the association. Men were “cordially invited to become Honorary members,” but the Board of Directors was comprised entirely of women.

Although women’s rights were not supported by the majority of Bostonians, the Association did have some allies. For instance, in its 2 April 1874 issue, The Index: A Weekly Newspaper Devoted to Free Religion, introduced the Association’s statement by writing:

We have been requested…to give a ‘word of notice’ to the following circular; but we find it so excellent that it seems proper to publish it in full in THE INDEX, with our heartiest approval of the organization and its object. Similar ones ought to be everywhere established; and the attention of all friends of the cause of women is called to one of the best plans yet devised to further it.

Nineteenth-century society provided independent women with very few legal and social rights, so these Bostonian businesswomen decided to organize and unite to protect themselves (and each other). Their circular states:

The constant complaint among women is that nothing is done to help them, pecuniarily, as a body, in case of need. The constant response of men is, that women will not unite as do men to help each other…by becoming members of, and thus supporting this association, women will not only effectually disprove the charge, but they will by this simple method do more to defeat the evil effects of unjust wages to women…

This last point seems particularly poignant and timely given that in mid-September, the United States Senate yet again blocked the passage of the Paycheck Fairness Act, a bill that would have strengthened equal pay protections for women. Despite the valiant efforts of these pioneering ladies, women are still fighting to be paid equal wages, one hundred and forty years later. Perhaps we should look to these revolutionary nineteenth-century women for some twenty-first-century inspiration in our continued fight for gender equality.