By Susan Martin

The guide to the Perry-Clarke collection is now online! Originally acquired by the MHS back in 1968, this collection has been available for research since then, but the old unwieldy paper guide needed a major overhaul. We hope this streamlined, fully searchable online guide will bring even more researchers to these wide-ranging and important materials.

Primarily the papers of Unitarian minister, transcendentalist, author, and reformer James Freeman Clarke (1810-1888) and his family, the collection consists of 64 boxes of correspondence, sermons, lectures, journals, notebooks, and other papers and volumes. Included are papers of Clarke’s wife Anna (Huidekoper) Clarke and members of the Huidekoper family, who were involved in the establishment of Meadville Theological School in Meadville, Pennsylvania, as well as papers of James and Anna’s children, Lilian, Eliot, and Cora. Much of the collection documents the family’s interest in social reform movements.

The Perry-Clarke collection may be best known to our researchers as the home of the 1844 journal and commonplace-book of Margaret Fuller, a close friend of the family. But I found many other items equally interesting. For example, one small manuscript diary entitled “Notes of a Nile voyage by S. A. Clarke, 1873.” S. A. Clarke was James’s older sister Sarah Anne, better known, it turns out, by the name she adopted later, Sarah Freeman Clarke (1808-1896). She was an accomplished artist, teacher, and philanthropist, and her Nile diary is that of a well-educated, well-traveled, late-Victorian American woman in an unfamiliar country.

Here’s an excerpt from 22 Dec. 1873:

We left Alexandria at ten o’clock A.M. The way was of perpetual interest. The camels pleased us particularly, walking along the embankment. They walk with their long necks stretched out, and their heads well up. They are ugly, but most picturesque, and one never tires of watching their solemn stride. They carry wonderful burdens. Four or five large building stories bound together with ropes, on each side, and which must bruise them at every step, is a common burden. They are the most patient of laborers, and with their backs piled with burdens, and an Arab on the top of all they make a most sketchable mass.

And about two months later inside one of the temples at Karnak:

In the room next to that where is a portrait of Cleopatra, I unfold my easel to make a sketch of some Sphinx heads which lie there. The sun glares in at the door and the noise of the Arabs without is distracting. I close the door and the place is now lighted only from some holes in the roof. There is light enough for me, but if I move the dust rises in clouds. Is this the dust of the Ptolemaic or the Pharaonic dynasty? It is very choky. The flies are also tormenting. They are the direct descendants of the flies that Moses procured to plague Egypt. […] As I sit there working alone the spirit of the past comes over me with much power. I have never been so near the old Egyptians as at this moment. […] I get a Sepia sketch of this suggestive corner. There is no time for more. The door opens, the Arabs scream, my friends come to look me up and we must go on. But I have added something important to my gallery of memories, and also to my portfolio of sketches.

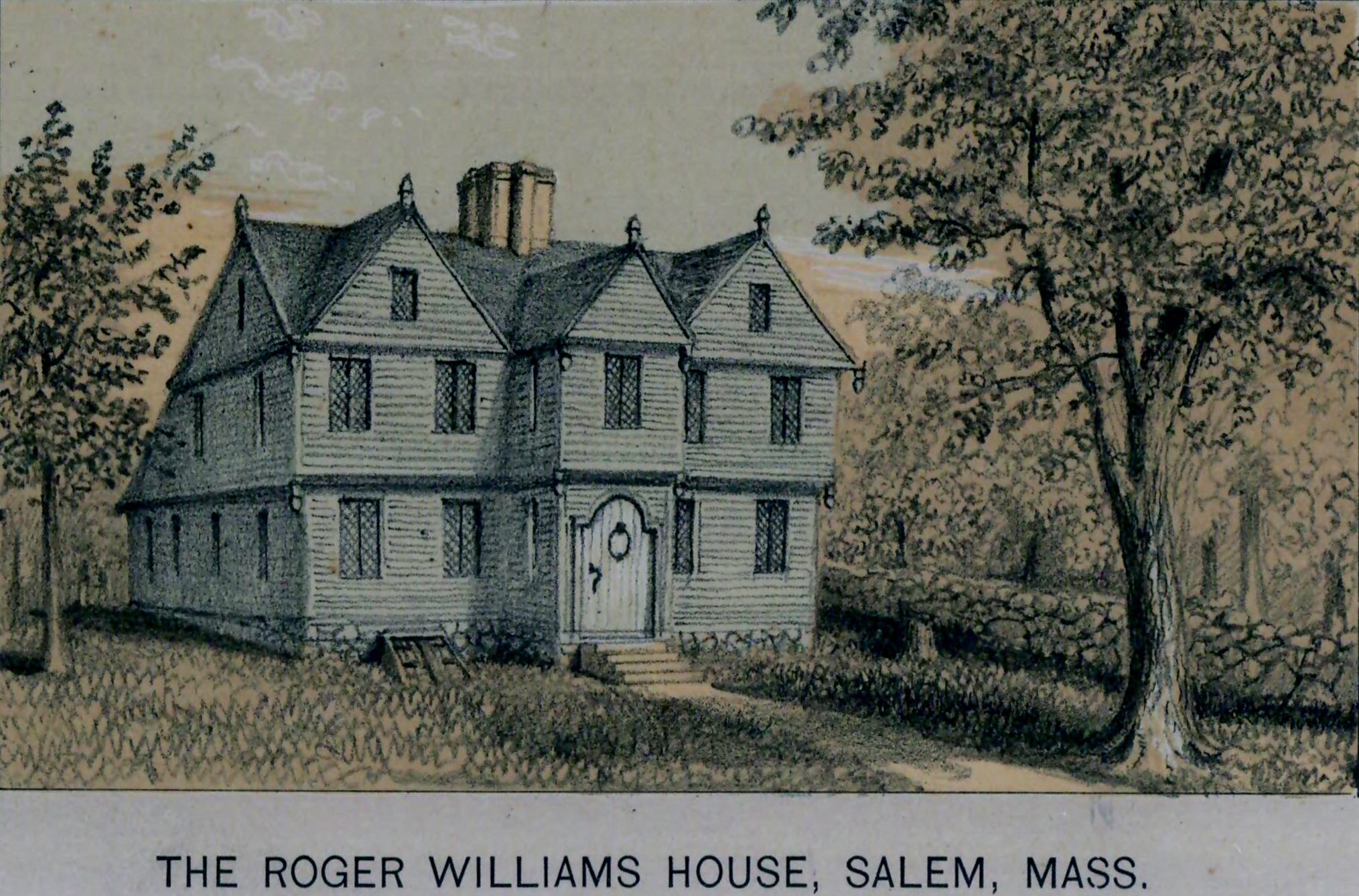

Sarah Freeman Clarke sailed the Nile in a dahabeah like this one (from the Perry-Clarke collection)

To learn more about James Freeman Clarke, Margaret Fuller, and the Clarke and Huidekoper families, see ABIGAIL, the online catalog of the MHS.