By Elizabeth Pacelle, John Winthrop Student Fellow

Working with the MHS primary source documents for the John Winthrop Fellowship was an amazing and rewarding experience for me. Besides analyzing various pieces of the Constitution and other common writings, I had never worked so closely with first hand historical documents. For my fellowship, I wrote a paper investigating women’s involvement in World War I overseas, and how their achievements directly linked to women’s suffrage. The MHS documents provided such rich evidence for the themes that I was exploring in my paper.

I was able to analyze the original letters of a young woman named Nora Saltonstall as written to her family. Nora was a Boston socialite who yearned to contribute to the American war efforts in WWI more actively and directly than women had done previously. She volunteered to go overseas to Europe to work on the warfront. It was fascinating to read Nora’s intimate letters and get a glimpse into a personal experience that related to such a greater movement. At points in the letters, Nora’s sense of humor and wittiness were evident which reminded me that she was indeed human and brought to life the events that transpired, in a way that textbooks are unable to. The collection contains digitized images of the very stationery she wrote on and her actual handwriting. She dated and gave her location to each of her letters and conveyed the events in her own words, giving the reader such a vivid perspective into Nora’s world at that time. The MHS also had photographs of Nora and her companions, her lodgings and workplaces, and even her passport. These primary source documents, gave me an eyewitness view to her experience, and made for a more interesting paper.

It is amazing how many letters and other primary sources from the MHS collection have been digitized, making them so easy to access. The MHS also provides transcriptions of all the digitized documents, which make it easier to search the documents for specific evidence you might be looking for. The online collection is well-organized and easy to navigate. It allows you to search by subject, era (from Colonial Era to the present) or medium (photographs, maps, even streaming medium), so you can directly access information on the topic you are pursuing and view different types of sources, which provide different layers of evidence. In my project I analyzed letters in the form of manuscripts, and backed up my claims with descriptions of photographs and other gallery images that further emphasized my points. I would suggest looking for correlations between the photographs and writings provided as different means of evidence.

I based my project on the documents in the Massachusetts Historical Society’s online catalog, Abigail, but the MHS library is also an incredibly valuable resource. If you are looking to get a firsthand glimpse into a historical figure’s life, you should check out the MHS collection. I suppose what I liked most was the ability to interpret the original documents on my own and draw my own conclusions around the actual evidence, rather than directly being told a conclusion by a third party. The MHS collection is well-worth looking into when you are researching American history topics.

**In 2013, the MHS awarded its first two John Winthrop Fellows. This fellowship encourages high school students to make use of the nationally significant documents of the Society in a research project of their choosing. Please join us in congratulating our fellows: Shane Canekeratne and his teacher Susanna Waters, Brooks School, and Elizabeth Pacelle and her teacher, Christopher Gauthier, Concord-Carlisle High School.

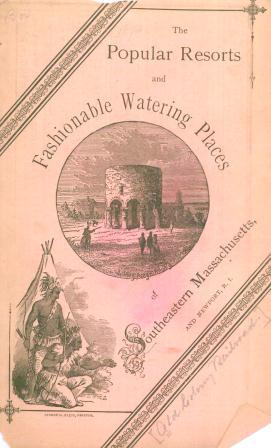

“Within a few hours’ ride from the metropolis are sections of country and seaboard, which in variety of character, loveliness of climate, and grandeur of scenery, are unsurpassed by any of the celebrated and more distant watering places on the continent,” wrote the unknown author of an Old Colony Railroad Company publication entitled, “Southeastern Massachusetts: Its Shores and Islands, Woodlands and Lakes, and How to Reach Them.” Having spent a few weeks utilizing the Old Colony Railroad system to travel throughout southeastern Massachusetts, the author wrote a guide for other adventurous vacationers in what is essentially a wonderfully descriptive, 49-page advertisement. The pamphlet lists more than 70 destinations, including traditional summer locales such as Provincetown, Martha’s Vineyard, and Nantucket and the less exotic locations such as Taunton, Foxboro, and Attleboro.

“Within a few hours’ ride from the metropolis are sections of country and seaboard, which in variety of character, loveliness of climate, and grandeur of scenery, are unsurpassed by any of the celebrated and more distant watering places on the continent,” wrote the unknown author of an Old Colony Railroad Company publication entitled, “Southeastern Massachusetts: Its Shores and Islands, Woodlands and Lakes, and How to Reach Them.” Having spent a few weeks utilizing the Old Colony Railroad system to travel throughout southeastern Massachusetts, the author wrote a guide for other adventurous vacationers in what is essentially a wonderfully descriptive, 49-page advertisement. The pamphlet lists more than 70 destinations, including traditional summer locales such as Provincetown, Martha’s Vineyard, and Nantucket and the less exotic locations such as Taunton, Foxboro, and Attleboro. Come ye whose sore and weary feet

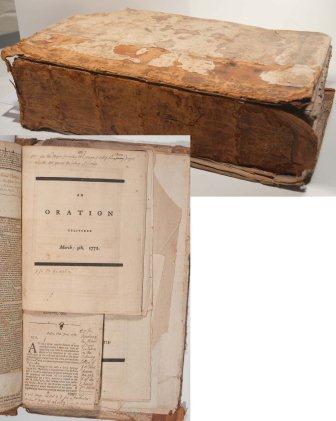

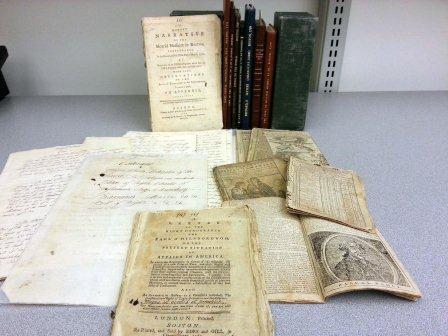

Come ye whose sore and weary feet We do not know when this happened, but the volumes were disbound at some point for, among other reasons, preservation. As part of this process, the pamphlets originally collected by Dorr for Volumes Two and Three were removed and added to the Society’s general collection of printed materials. These two volumes came to the MHS in 1798 and have been in use for more than 210 years. This means there is a long period of time in which some of the documents Dorr collected may have been separated and moved around. In 2011, the MHS acquired the fourth volume of Dorr’s Annotated Newspapers via auction. Working at the MHS when this fourth volume arrived, and seeing how it looked in its original organization and binding, I became intrigued about the existence of those pamphlets that had been separated from the earlier volumes, and where they might be located within the building.

We do not know when this happened, but the volumes were disbound at some point for, among other reasons, preservation. As part of this process, the pamphlets originally collected by Dorr for Volumes Two and Three were removed and added to the Society’s general collection of printed materials. These two volumes came to the MHS in 1798 and have been in use for more than 210 years. This means there is a long period of time in which some of the documents Dorr collected may have been separated and moved around. In 2011, the MHS acquired the fourth volume of Dorr’s Annotated Newspapers via auction. Working at the MHS when this fourth volume arrived, and seeing how it looked in its original organization and binding, I became intrigued about the existence of those pamphlets that had been separated from the earlier volumes, and where they might be located within the building. There are currently two page ranges within Volume Two for which we still do not have images: 939 to 946 and 1041-1098. However, from an index entry and research, I have concluded that the first range (939-946) is the breathtakingly titled pamphlet: A Third extraordinary budget of epistles and memorials between Sir Francis Bernard of Nettleham, Baronet, some natives of Boston, New-England, and the present Ministry; against N. America, the true interest of the British Empire, and the rights of mankind by Sir Francis Bernard (1769). Likewise, index terms for the second range listed above (1041-1098) lead us to conclude that this span consisted of parts of three separate almanacs published in 1768 and 1769. See the

There are currently two page ranges within Volume Two for which we still do not have images: 939 to 946 and 1041-1098. However, from an index entry and research, I have concluded that the first range (939-946) is the breathtakingly titled pamphlet: A Third extraordinary budget of epistles and memorials between Sir Francis Bernard of Nettleham, Baronet, some natives of Boston, New-England, and the present Ministry; against N. America, the true interest of the British Empire, and the rights of mankind by Sir Francis Bernard (1769). Likewise, index terms for the second range listed above (1041-1098) lead us to conclude that this span consisted of parts of three separate almanacs published in 1768 and 1769. See the