By By Laura Prieto, Simmons College

Love letters come in many varieties, but there’s a resonant familiarity about the language of longing.

Alice Bache Gould and Henrietta Child came of age as neighbors on Kirkland Street in Cambridge. The young women shared a keen love of books, and enjoyed discussing their ideas and projects. Literary accomplishments marked the male and female lines of both of their families; Alice’s relatives included poet Anna Cabot Lowell Quincy Waterston, and author Catharine Sedgwick was Henrietta’s great-aunt.

Henrietta continued her studies informally while Alice’s ambitions took her away from New England: to Bryn Mawr for a bachelor’s degree and eventually to the University of Chicago for doctoral work in mathematics. Alice hoped for a career as a scholar and university teacher while Henrietta felt an obligation to her family at home. In 1896, both young women lost their brilliant fathers, astronomer Benjamin Apthorp Gould and Harvard professor Francis James Child. Alice continued to travel in ever wider circles, from Cambridge to Chicago to the Caribbean. She could not land the kind of teaching positions she wanted and she found it increasingly hard to work on her dissertation.

Through those restless years, Alice stayed bound to Henrietta through letters. They wrote lengthily and often, sometimes daily. Advice, observations, jokes, recipes, and frivolities, all have their place on the pages exchanged. The two women even continued their serious studies together through their correspondence, taking up the History of Mathematics written in 1758 by French author Jean Étienne Montucla (1725-1799). Alice visited Henrietta in October 1902 before embarking for Puerto Rico with another friend and neighbor, Susie Preble. “I see the Navy has followed you to have a sight of those low-necked dresses you took with you,” teased Henrietta.

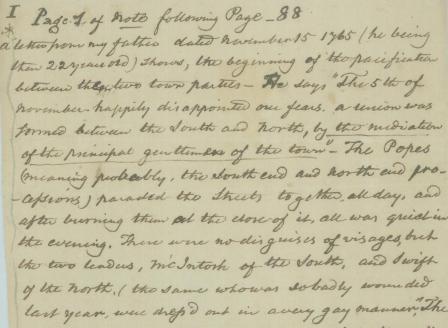

Alice and Henrietta’s affection and intimacy are always in evidence, but their long separation in 1902-1903 led Henrietta to chafe against her “duty” to stay with her mother and sister. (Alice Bache Gould Papers, MsN-1309, Box 14, Folder 9) She confessed to Alice,

I have been indulging in thoughts, or dreams perhaps, about you, thinking how it would be if we could go off together, how we should get along — whether you would not be almost as depressed with me as without me, but still that I would risk it gladly if it were right to leave home — because I did not like to have you go off by yourself & I thought in some ways it would be a change that I could put to use. I could study & cheer you up a bit & together — Well the rest was sentiment & not over wise, not according to the real way of life I suppose.

I am going to Montucla now, & be sensible.

Your loving friend,

Henrietta

I think of you a lot.

Don’t be discouraged, my little girl. Keep up brave heart, & try to make the best of things just as they are, then they will not be so bad. I should like to be beside you to night when the lights were out & then we could have a talk.

Henrietta’s language is so passionate, and seems so un-self-conscious. What should we make of it? In the 1970s, women’s historians like Carroll Smith-Rosenberg began to study the “romantic friendships” that blossomed between women in nineteenth-century America. These intense relationships often began at school and were nurtured within the “female world” of the domestic sphere, wherein women were supposed to be the affectionate, sentimental, innocent sex. In adulthood, such relationships could co-exist alongside a woman’s conventional male-female courtships and marriage, or they could become her primary commitments. When the women in question lived together, they might be called a “Boston marriage.” Whether they were lovers in a physical sense is usually impossible to prove either way, and scholars differ on whether the sexual aspects even matter. Are the erotic possibilities essential or a prurient distraction?

They never lived together, as Henrietta fantasized doing; but Henrietta Child and Alice Bache Gould fit the quintessential profile of romantic friends. They were well educated women of a certain social class who addressed one another with deep love and intimacy. They expressed their feelings for one another in the language of courtship, welcomed physical closeness, and used playful, maternal endearments (“my little girl”). They never married. If anything is surprising to the historian in their letters, it is their timing. Henrietta wrote her letter a decade after the sensationalized trial of Alice Mitchell, who said she murdered her dear friend Freda Ward “because she loved her” and could not be with her. The court and the press accused Mitchell of “unnatural affection,” sexual perversion, and insanity. By then, the theories of Richard von Krafft-Ebing and other pioneers of sexology had begun to classify “homosexuality” as a psychiatric disorder. Publicity cast new suspicion on intense same-sex friendships, making unseemly what had no one had objected to before. Yet in early 1900s Cambridge, proper young women could still “indulge” in feelings of love for one another.

Alice’s search for fulfillment eventually took her to Simancas, Spain, where she conducted ground-breaking archival research on Columbus’ first voyage and worked for the U.S. embassy during World War I. Henrietta ended up on an adventure of her own. In 1911, after her mother’s death, she left New England to teach at the Hindman Settlement School in rural Berea, Kentucky. She spent the rest of her life there, as an inspiring storyteller in the local school system.

An increasingly hostile climate and the pressures of family may have kept them from “going off together;” but their loving friendships helped give Henrietta and Alice the strength to pursue meaningful lives, on their own terms.

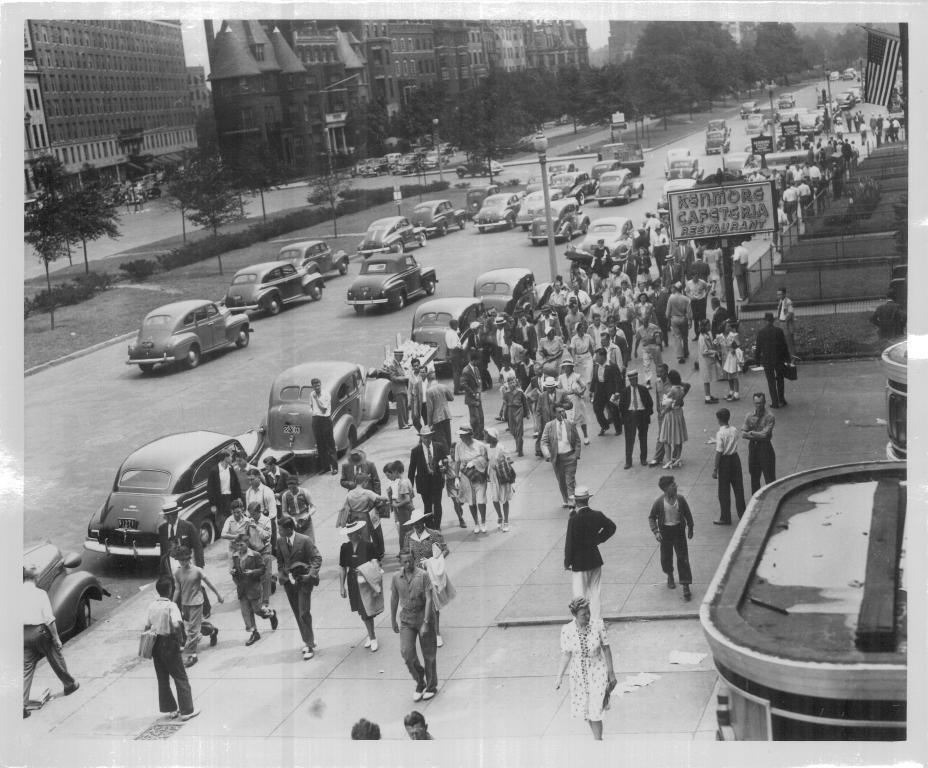

While a modern day parade that hails our sports teams as champions draws thousands of loyal fans to the streets, none will celebrate an event that had such an impact on the city or attract such a diverse crowd. While some put their hopes and emotion into supporting the Bruins or the Red Sox and cheer their victories, this was a cause to celebrate lives saved and enriched.

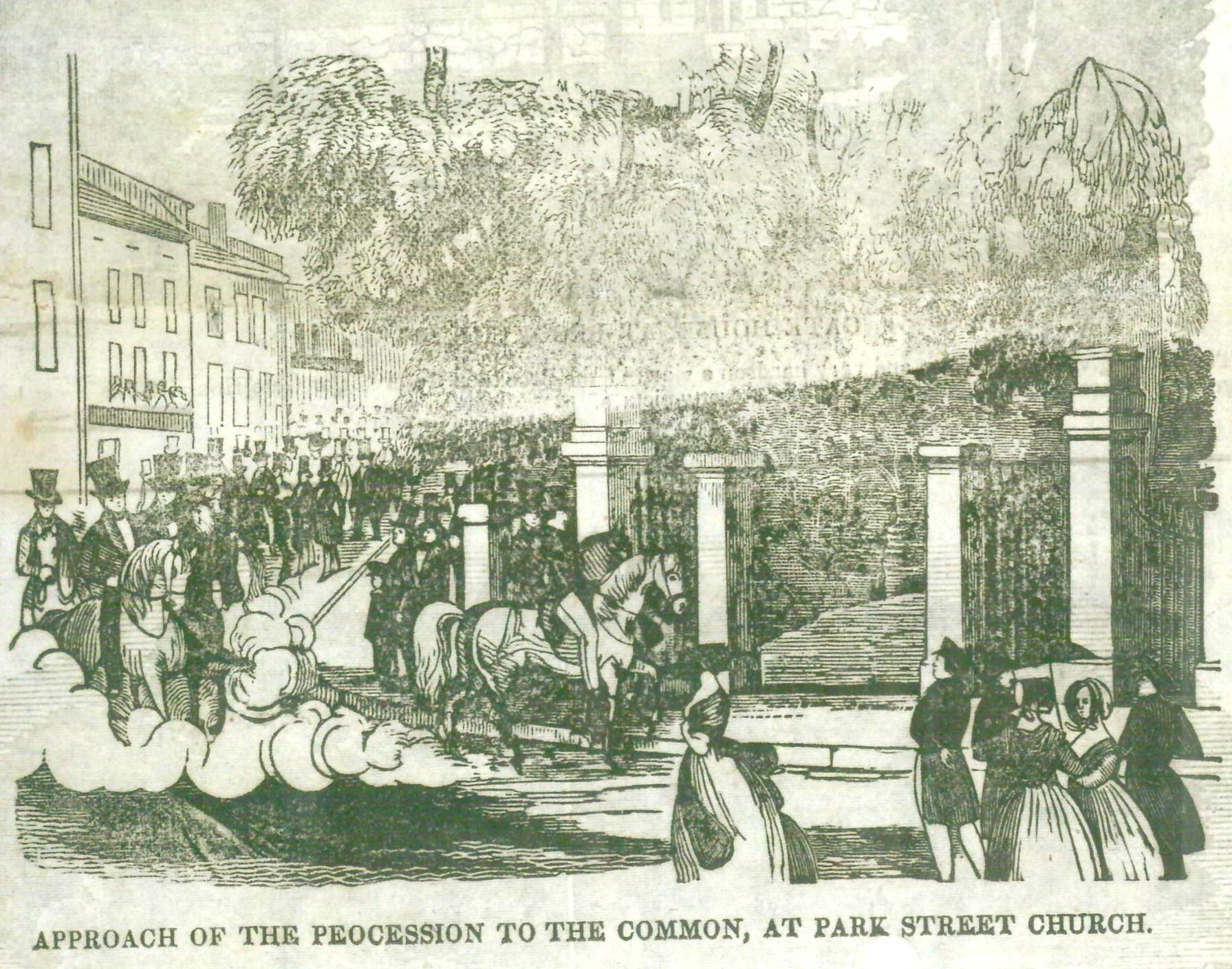

While a modern day parade that hails our sports teams as champions draws thousands of loyal fans to the streets, none will celebrate an event that had such an impact on the city or attract such a diverse crowd. While some put their hopes and emotion into supporting the Bruins or the Red Sox and cheer their victories, this was a cause to celebrate lives saved and enriched. The procession ended at Boston Common, at which point the performances began. There was singing by the Handel & Haydn Society, a prayer by a reverend minister, an ode sung by schoolchildren and penned by James Russell Lowell. A report on behalf of the Water Commission followed, along with an address by the Mayor. Finally, the water was turned on and the chorus from the Oratorio of Elijah was proclaimed.

The procession ended at Boston Common, at which point the performances began. There was singing by the Handel & Haydn Society, a prayer by a reverend minister, an ode sung by schoolchildren and penned by James Russell Lowell. A report on behalf of the Water Commission followed, along with an address by the Mayor. Finally, the water was turned on and the chorus from the Oratorio of Elijah was proclaimed.