By Tracy Potter

Over the last several months Jeremy Dibbell, Anna Cook, and I have been tantalizing all of you with peeks into the library’s latest project, Presidential Letters at the Massachusetts Historical Society: An Overview. I am glad to announce that as of the 23 February 2010 the project has finally come to its completion and the completed finding aid is now available online at http://www.masshist.org/findingaids/doc.cfm?fa=fa0329.

This subject guide is an overview of the MHS’ holdings of all known letters written by presidents found in the Society’s manuscript and autograph collections. The guide now lists over 5,400 letters written by every U.S. president except for William Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama. This number does not include the letters found in the Adams Family Papers and the Coolidge Collection of Thomas Jefferson Manuscripts for John Adams, John Quincy Adams, and Thomas Jefferson.

This very large project was completed over a relatively small period of time (five months to be exact), which could not have been done without the assistance of several people.

– L. Dennis Shapiro, a Trustee of the Society, who developed the original idea of the project with Peter Drummey, provided funding for the project through the Arzak Foundation, and gave feedback throughout the project.

– Peter Drummey, the Stephen T. Riley Librarian, who developed the original idea of the project with Trustee L Dennis Shapiro, helped brainstorm formatting and content, provided me with locations of important letters and tidbits of information on presidents.

– Brenda Lawson, the Director of Collections Services, who helped brainstorm formatting and content and who also edited endless pages of presidential letter descriptions.

– Susan Martin, Manuscript Processor and EAD Coordinator, who helped encode the finding aid and gave both Sarah and me a tutorial on the use of XMetal.

– Sarah Desmond, Semester Intern from Endicott College, who spent 35 hours a week for three months looking through catalogs and collections, describing presidential letters, and formatting and encoding the finding aid.

I also would like to mention the assistance of the staff of the MHS who provided me with feedback and locations of letters that fell through the cracks.

Although the bulk of the guide is complete, please keep in mind that this is an ongoing project. As new collections come in and new collections are processed new letters could be added to the guide.

It was a pleasure working on this project and I hope all will enjoy it.

You can browse the guide here.

We’re happy to announce a new

We’re happy to announce a new  Our

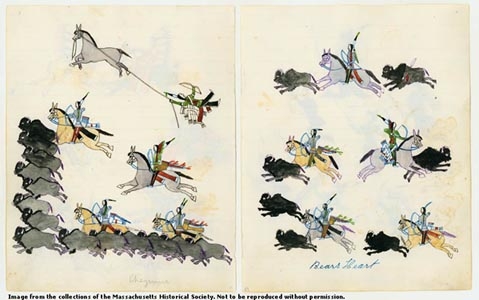

Our  One of the most interesting of our image collections here at MHS are the

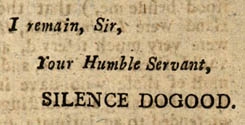

One of the most interesting of our image collections here at MHS are the  Many people have heard of Silence Dogood, and recognize that name as a pseudonym used by Benjamin Franklin, but how many people have read “her” words? The MHS has just launched a web exhibition, “

Many people have heard of Silence Dogood, and recognize that name as a pseudonym used by Benjamin Franklin, but how many people have read “her” words? The MHS has just launched a web exhibition, “