By Jeremy Dibbell

Picking up right where we left off yesterday, this post continues the saga of the Shepard library biblio-sleuthing expedition. As I wrote, I thought it might be worth checking to see whether we had any Shepard family books here at MHS, and if so whether they exhibited any of the marking patterns seen in the copies at Princeton. Our various catalogs resulted in the discovery of six books with Shepard provenance (and I suspect there may be a few more lurking in the stacks that I’ve yet to find). The titles we know so far are:

1. Thomas Goodwin, The returne of prayers: a treatise vvherein this case, how to discerne Gods answers to our prayers, is briefly resolved : with other observations upon Psal. 85.8 concerning Gods speaking peace, &c. (London: Printed for R. Dawlman, and L. Fawne at the signe of the Brazen serpent in Pauls Church-yard, 1636).

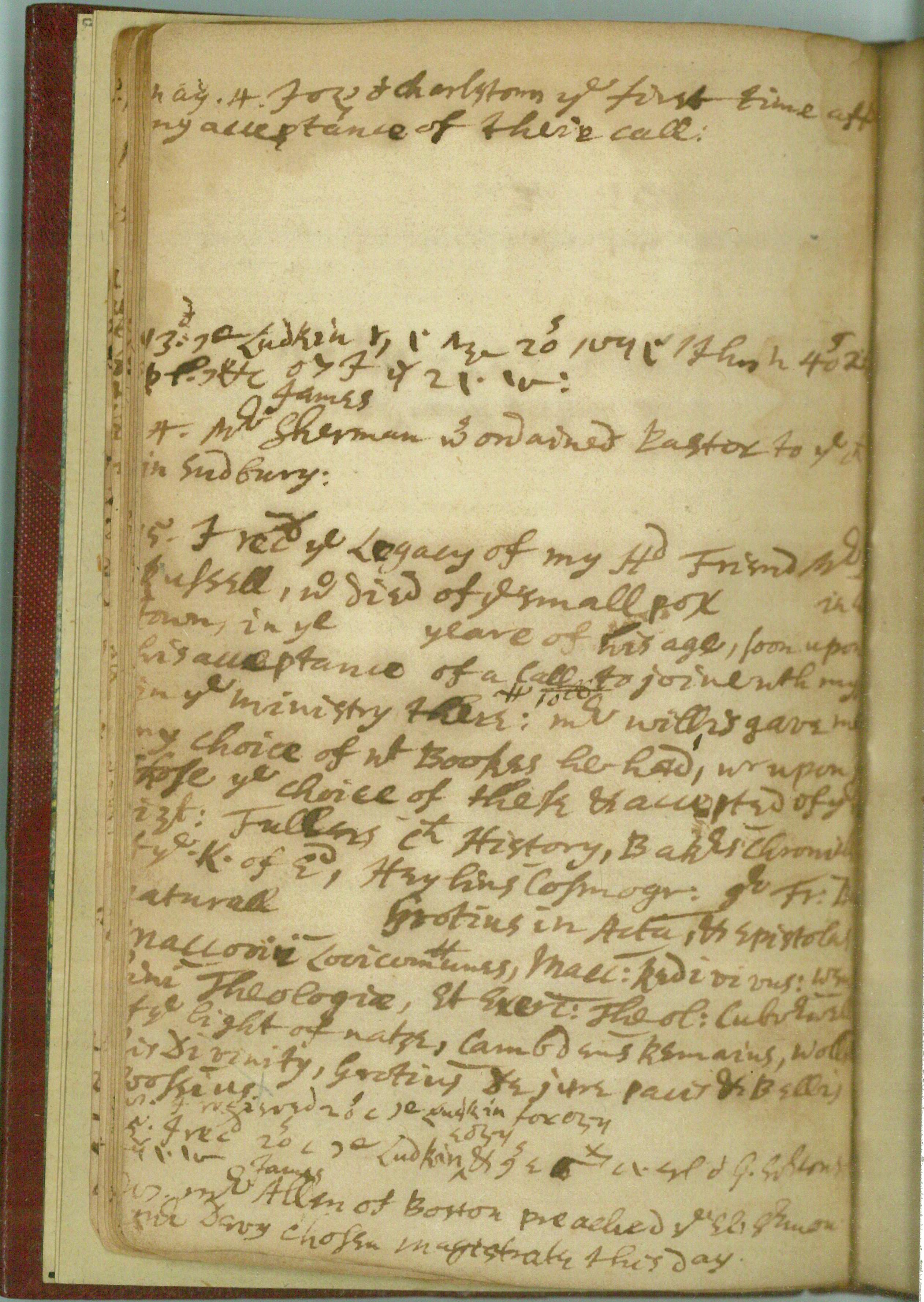

Notes: On front pastedown: MHS bookplate, noting Gift of “Miss Susan Minns, May 1, 1931”; inscribed below bookplate, “W. Beaman [?] 1905”; inscribed on title page [A2r]: “price 1s 4d”; inscribed on verso of title page [A2v]: “Thomas Prince Charlestown 1707 / [1?]s 4d silver.”; inscribed sideways on A3r, in ornate script: “Thomas Shepard me dedit 1652”; inscribed at top margin, A3r: line of shorthand, above which “Prince” (partially obliterated); inscribed on p. 396, sideways: “Thomas Shepard me tenet [?] and several shorthand marks at foot of page. Contains the “TS” stamp on the top edge.

2. William Gouge, A learned and very useful commentary on the whole epistle to the Hebrews : wherein every word and particle in the original is explained … : being the substance of thirty years Wednesdayes lectures at Black-fryers, London by that holy and learned divine Wiliam Gouge … : before which is prefixed a narrative of his life and death: whereunto is added two alphabeticall tables (London: Printed by A.M., T.W. and S.G. for Joshua Kirton, 1655). Second volume.

Notes: Inscribed on front flyleaf: “Tho: Shepards Booke / 1659: May. 19 / prot. 40s”; below same: “Warham Williams his Book 1738”; in pencil further down on page: “From J.B. Thayer / Feb. 1886”; inscribed on title page: “Warham Williams 1738 25/”. Contains a very clear “TS” mark on the top edge (pictured below).

3. Christopher Airay, Fasciculus praeceptorvm logicorum: In gratiam juventutis Academicae compositus & typis donatus (Oxoniae: Excudebat H.H. Impensis Jos. Godw., 1660).

Notes: Inscribed on front pastedown: “Presented to the Mass Hist’l Soc’y by Horatio G. Somerby”; inscribed on title page: “Thomas Shepardus [ejus?] liber prst[?] / 18 . 8’o 1674”; inscribed on verso of title page: “Edward Michesson [?] / His Book / 69”; inscribed on page *3, upside down at foot: “John green His Book / 1670”. Contains several glosses in text. Smudged/unclear “TS” mark on top edge.

4. John Cotton, Some treasure fetched out of rubbish: or, Three short but seasonable treatises (found in an heap of scattered papers) which providence hath reserved for their service who desire to be instructed, from the Word of God, concerning the imposition and use of significant ceremonies in the worship of God (London: [n.p.], 1660).

Notes: Inscribed sideways on title page: “Thomas Shepards booke 1660 5s [?]”; additional notes on title page; scattered shorthand and plaintext glosses through p. 15. No “TS” mark on top edge (too thin).

5. John Cotton, Of the holinesse of church-members (London: Printed by F.N. for Hanna Allen, and are to be sold at the Crown in Popes-head Alley, 1650).

Notes: Title inscribed on front flyleaf in an early hand; below this, “Wm Jenks A’o 1814.”; inscribed on second front flyleaf, long paragraph in shorthand with short plaintext gloss; inscribed on title page: “Thomas Shepard’s Book”; further note on verso of title page; inscribed on last leaf (blank): “Thomas Shepard’s Book 1660”; below this, notes referring back to pp. 42, 90. No “TS” mark on top edge (too thin).

6. [Synopsis purioris theolgiæ: disputationibus quinquaginta duabus comprehensa, ac conscripta per Iohannem Polyandrum, Andream Rivetum, Antonium Walæum, Antonium Thysium (Lvgduni Batavorvm: Ex officina^ Elzeviriana, 1632).]

Notes: Missing title page. On front pastedown: MHS bookplate noting gift of “Horatio G. Somerby / Nov. 1 1843”; inscribed on first blank: “Thomae Shepardi liber / 21. 3’o 1677”; inscribed below: “Edwardi Parsoni / Liber ex dono superscripti quondam possesoris / 1677” Lightly next to this, “Pret 3s-6d.”; inscribed below this: “Sam’th Parson / 1714”; various pen tests (mostly ggggg) around page. Later notes (librarian’s) on verso of ffep given title information (suggesting this is the 1652 edition, with later penciled note suggesting 1625). Insribed on last full leaf: additional note about Somerby gift to MHS, 1843, and some partially torn away earlier notes on the verso. No “TS” mark on top edge.

Beyond these books at MHS, we’ve also been able to confirm a few other Shepard titles at other libraries, including six that ended up in the Mather collection now at the American Antiquarian Society (I think before we’re done we’ll discover that they have a few more Shepard books, too); one at the John Carter Brown Library; and one at the Morgan Library. Those at the AAS all have the “TS” mark on the top edge (look for a blog post from them on this topic too), and our former MHS colleague Kim Nusco who’s now at the JCB reports that their book was rebound and gilded, probably destroying any edge-mark that used to be there (there’s a glimmer of hope that a trace of the mark might remain).

These discoveries seem to indicate that at least some of the Shepard books probably left the family and did not travel the same path as the Princeton books did, although we’ve yet to determine exactly how they made their way down through the centuries. That remains to be explored, but the names gathered from our copies (i.e. Thomas Prince, Warham Williams, William Jenks, Edward Parson) offer some interesting leads and points of exploration, some of which will be explored in future posts. In the meantime, if you know of any additional Shepard books, please let us know!

Just a brief update on some of the latest discoveries in our research on the Thomas Shepard books (see

Just a brief update on some of the latest discoveries in our research on the Thomas Shepard books (see

To mark the 100th

To mark the 100th  Part of our new website design (well not so new anymore, I can’t believe it

Part of our new website design (well not so new anymore, I can’t believe it  Our December

Our December  One of the MHS digital collections currently being highlighted on our homepage is

One of the MHS digital collections currently being highlighted on our homepage is