By Rakashi Chand

This is a lovely time of year to visit the beautiful province of Quebec, Canada. Quebec City is a special hidden gem, the feel of Europe without boarding a plane! But many Americans crossing the border are not aware of American invasions of Canada (most significantly, the Quebec expedition, during the American Revolution).

The first Continental Congress invited the French-Canadians to join their cause, hoping to appeal to their desire to be rid of British rule. Although this union never came to fruition, there was perhaps the possibility of a fourteenth colony. France had recently lost the Province of Quebec to the British in the French and Indian War so the Americans forces hoped the French Canadians would join them in over-turning British rule in North America when they invaded Quebec. This was the first major military excursion for the young Continental Army. General Richard Montgomery led a successful campaign in Montreal, but his snow-storm assault on the last day of the year in 1775 ended in disaster below the heavily fortified walls of Quebec City.

The six-week trek from Boston to Quebec City through the Maine wilderness led to the creation of an interesting array of documents in testimony of the hardships endured and the battle which ensued. Here at the MHS, researchers can view the William Dorr Journal, 1775-1776, which describes the journey to Maine up the Kennebec River and down the Chaudiere to Quebec and the hardships incurred; Jonathan Hill Journal, 1776, which recounts the march from New York to Montreal (and is written on the back pages of an arithmetic copy book); the handsome penmanship of Benedict Arnold in a letter regarding the siege of Quebec in the Hector McNeill papers, 1765-1812. Alternatively, researchers can get the British perspective, through the Journal of an officer of the 47th Regiment of Foot, 1776-1777, kept during campaigns in Canada describing the regiment’s activities under Gen. Guy Carleton while reinforcing the Quebec area against American forces in 1776.

There are also numerous printed documents recounting the “Canadian Invasion.” The Quebec expedition turned out to be much more than what the Continental Army could manage the winter of 1775-76, but don’t take our word for it. You can read about the expedition through journals, letters, books and even a drama (The death of General Montgomery, in storming the city of Quebec: A tragedy By H. H. Brackenridge (Norwich [Conn.]: Printed by J. Trumbull, for and sold by J. Douglass M’Dougall, on the west side of the Great-Bridge, Providence, 1777). If this topic piques your interest, please use our on-line catalog, ABIGAIL, to do a subject search for “Canadian Invasion, 1775-1776”; to see a list of available sources. And the next time you cross the border or if you ever have a chance to walk through the fortifications of Old Quebec City, you can imagine the hardships encountered by General Montgomery, Benedict Arnold, and the continental army as they attempted to “take Canada”.

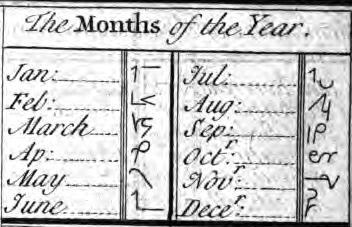

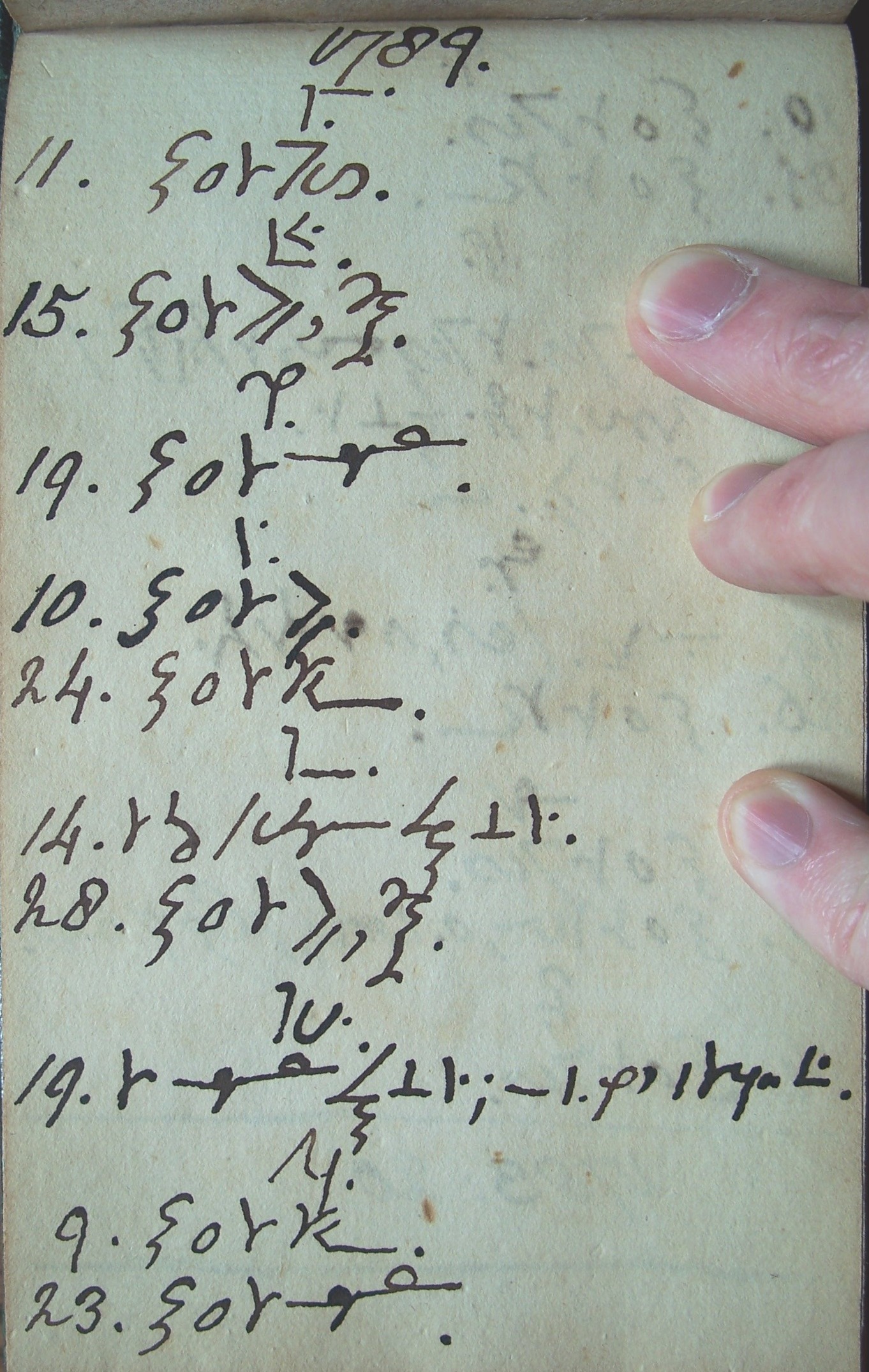

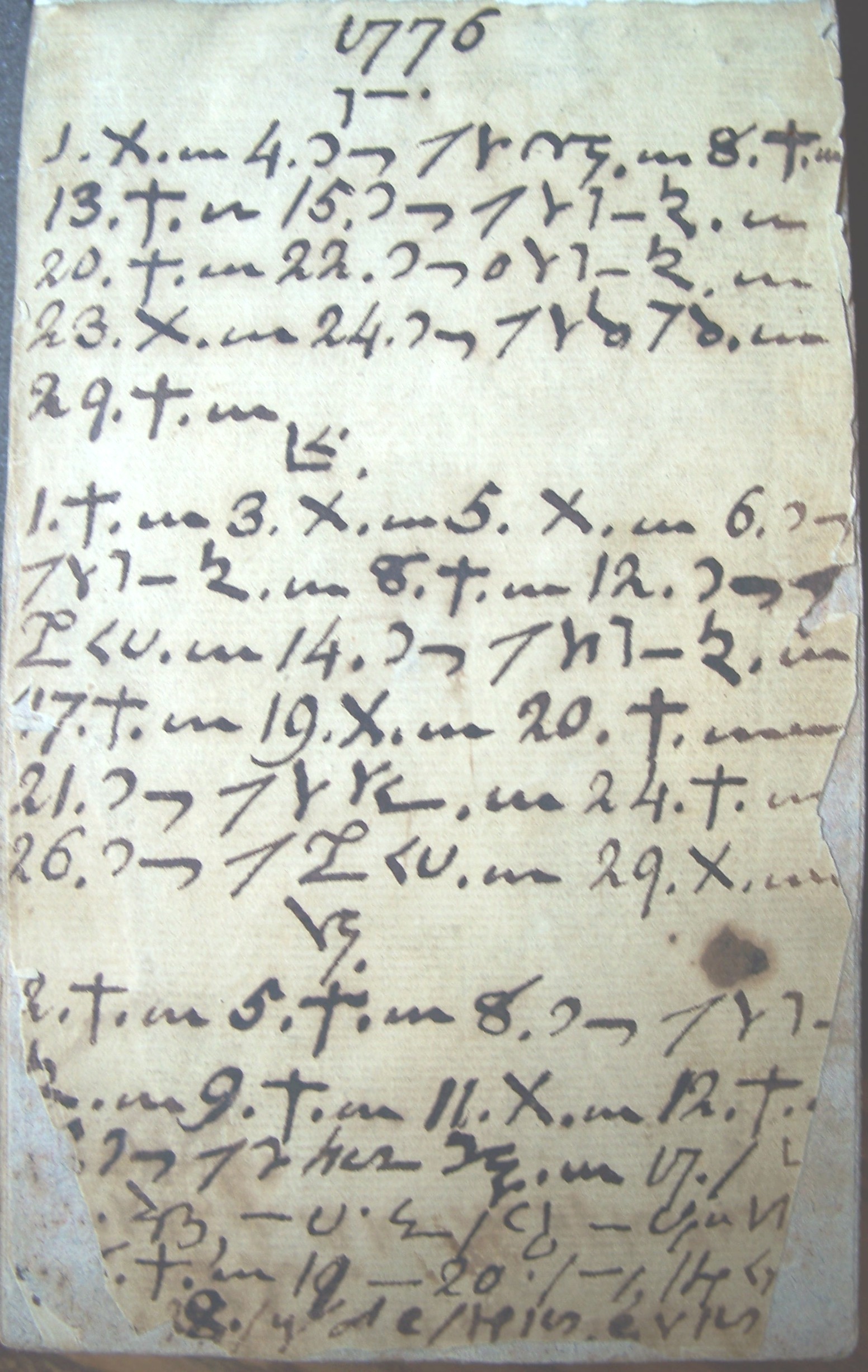

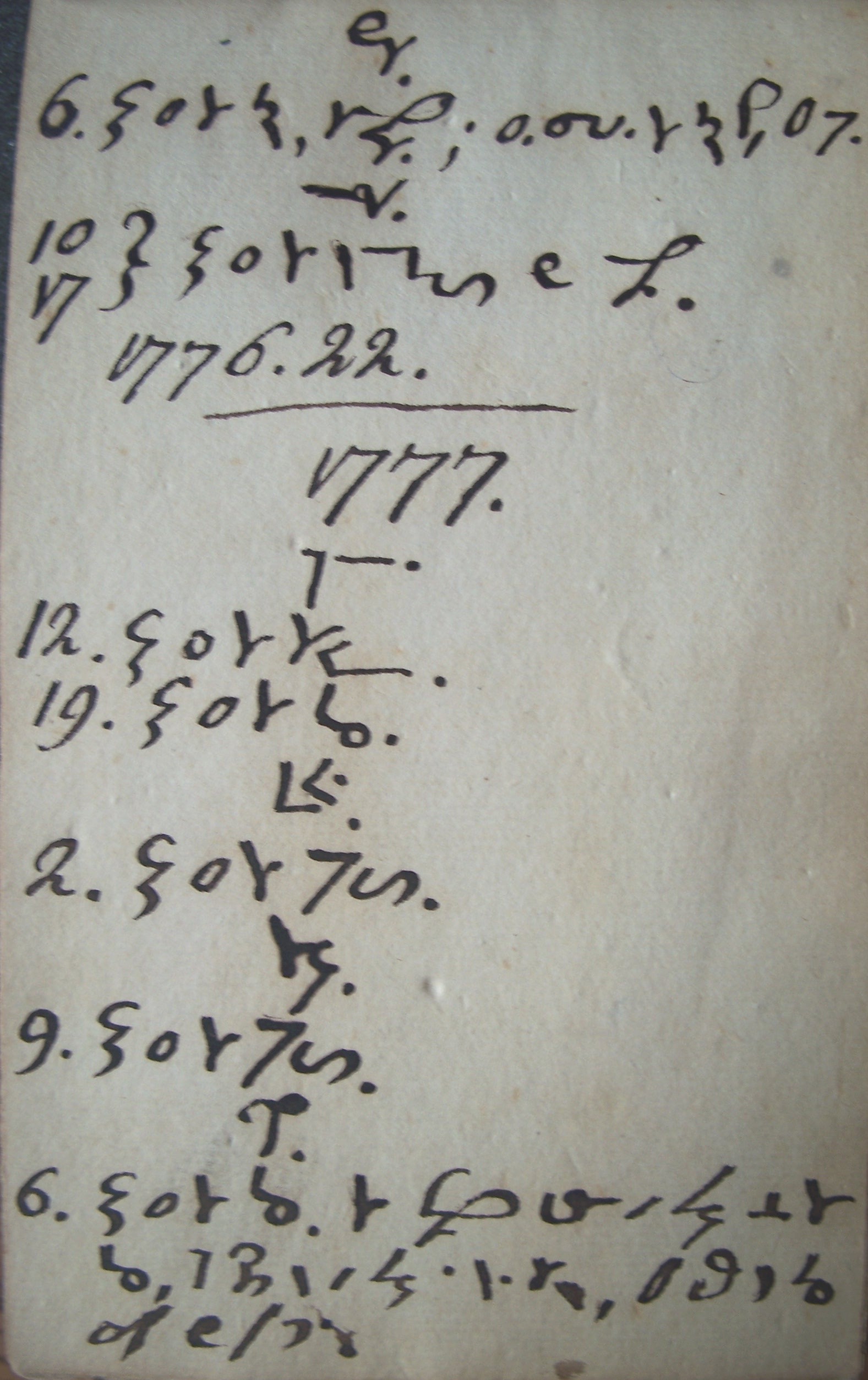

One of the items in our collections I find most intriguing is the “

One of the items in our collections I find most intriguing is the “ olume, expressed to me an opinion that it was a diary of a Clerygman, perhaps as has been conjectured, of Rev. Moses Parsons of Byfield. But the entries extend to 1799 – sixteen years after the death of that gentleman. J. Davis.”

olume, expressed to me an opinion that it was a diary of a Clerygman, perhaps as has been conjectured, of Rev. Moses Parsons of Byfield. But the entries extend to 1799 – sixteen years after the death of that gentleman. J. Davis.”