By Emilie Haertsch, Publications

On Wednesday Assistant Director of Education and Public Programs Kathleen Barker wrote about the recent teacher workshops held at the MHS. The week-long workshops, titled “At the Crossroads of Revolution: Lexington and Concord in 1775,” engaged 80 teachers from across the country, who will return to their classrooms with exciting material for their students. After the successful workshops, Barker sat down to talk with me about the Society’s ongoing educational work.

- Tell me about the history of education efforts at the MHS.

About 12 years ago MHS fellow David McCullough, whose son is a teacher, expressed an interest in developing educational efforts for teachers at the MHS. That led to the Society offering the Swensrud Fellowships for teachers beginning in 2001. That program continues today, in addition to other efforts. We have curriculum ideas available for teachers based on the materials in our collections. We also offer seminars where teachers have the opportunity to examine primary sources from our collections and take their discoveries back to their students. And we offer workshops for students and parents.

2. You recently completed two week-long summer workshops for teachers. What were the goals of these workshops?

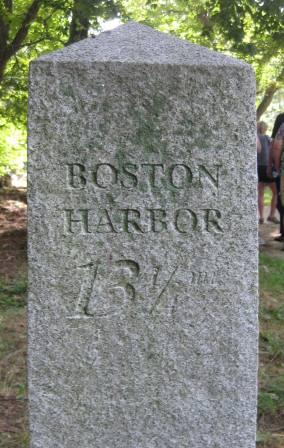

The workshops were part of the Landmarks of American History and Culture project funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the idea was to get teachers out into the landscapes where historical events happened. Our workshop was about Lexington and Concord during the Revolutionary War, so we took the teachers to those places. They were not in classrooms, but in barns, historic houses, and in Minute Man National Historic Park. We also spent time at the MHS and gave context to these places.

3. How have teachers been impacted by coming to educational events at the MHS?

Teachers from these recent workshops told us that they see history differently after being in the places where events took place, and they bring that to the classroom. Many teachers have told us they use our website in their classrooms, and they encourage their students to learn from documents from our online collections.

4. Why is it important that the rich materials in the Society’s collections reach young students?

The historical evidence in our collections helps students to develop critical thinking skills. Instead of taking the interpretation of their teacher or textbook at face value, they are able to examine original documents and form their own ideas. It’s also important to develop students’ interest in history, because they are the preservationists of tomorrow. If we want people to continue supporting historical work we need to foster a passion for history in today’s young people.

5. What are your plans for upcoming educational events at the MHS?

In the spring the Society will be cosponsoring National History Day. We’ll be holding workshops for both teachers and students for this event. Coming up on November 17th we have our Family Day, when the Society will be hosting a program for students and parents about the Revolutionary War. The Society also is planning the launch of a new website, so keep an eye out for updated curriculum help and program announcements in the Education section.

attended a dinner of the Sons of Liberty at Liberty Tree Tavern in Dorchester. A

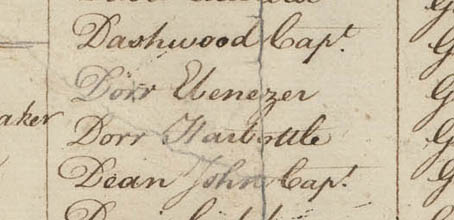

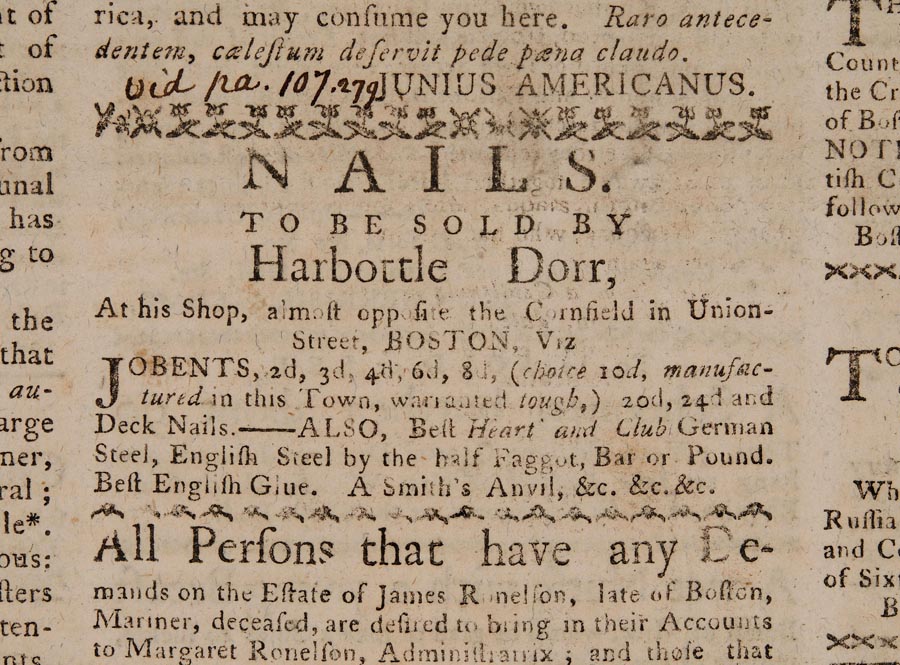

attended a dinner of the Sons of Liberty at Liberty Tree Tavern in Dorchester. A  A newspaper advertisement appearing in the 15 January 1770 issue of the Boston-Gazette, and Country Journal (on page 3) indicates that Dorr sold many kinds of nails and different types of steel in his shop located on Union Street. His inventory included jobents (nails used to fasten hinges and/or other thin iron plates to doors and window frames), deck nails (nails used to fasten planks to the decks of ships), German steel, and English steel. These details help us formulate a picture of Harbottle Dorr–at the counter of his shop, surrounded by hardware, with a newspaper open in front of him, writing in the margins in between transactions with customers.

A newspaper advertisement appearing in the 15 January 1770 issue of the Boston-Gazette, and Country Journal (on page 3) indicates that Dorr sold many kinds of nails and different types of steel in his shop located on Union Street. His inventory included jobents (nails used to fasten hinges and/or other thin iron plates to doors and window frames), deck nails (nails used to fasten planks to the decks of ships), German steel, and English steel. These details help us formulate a picture of Harbottle Dorr–at the counter of his shop, surrounded by hardware, with a newspaper open in front of him, writing in the margins in between transactions with customers.

By Wednesday participants were ready to take a closer look at the first day of the revolution. We toured many different sites, including Lexington Green, Paul Revere’s capture site, and the North Bridge in Concord, as we

By Wednesday participants were ready to take a closer look at the first day of the revolution. We toured many different sites, including Lexington Green, Paul Revere’s capture site, and the North Bridge in Concord, as we

Martha Hodes

Martha Hodes