By Susan Martin, Collection Services

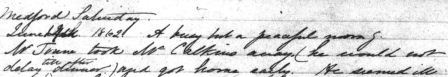

The MHS recently acquired a manuscript collection called the Russell-Cutter family papers (Ms. N-2866) that contains one particularly interesting item: a divorce agreement dated 30 April 1735. It reads, in part:

Know ye that James Smith of Boston in the County of Suffolk in New England Coachman and Hannah his Wife In Consideration of the want of mutual Love & Affection between them, and for sundry acts which they each of them acknowledge is the Strongest proof for any divorce in Law, Have Agreed and by these Presents do agree to and with each other to part and Seperate themselves Voluntarily, and never to molest or Disturb each other in any act or acts Business or Imployments whatsoever or even if Either of them should marry again, they will not prosecute each other but will Look upon themselves as though they had never marryd at all.

Not knowing much about divorce law in colonial America, I did a little digging and found that, although rare, divorce was by no means unheard of at the time. Massachusetts Bay granted the first divorce in the colonies in 1639. (The husband was a bigamist.) According to historian Peter Charles Hoffer, in Law and People in Colonial America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), the immigrants who settled in New England in the 17th century considered marriage a civil contract, not a religious sacrament. In fact, despite its Puritan beginnings, the New World had more permissive divorce laws than Anglican England. The laws varied from colony to colony and were generally more lenient in the north than in the south. Of course, social stigma would also have acted as a powerful deterrent.

Hoffer provides some helpful statistics:

In Massachusetts and in Connecticut, whose divorce practices were even more liberal than those of Massachusetts, there was rarely one petition per year in the seventeenth century. In the next century the number of petitions steadily increased. Between 1692 and 1785 the Massachusetts General Court heard 229 petitions for divorce, 101 of them from men, and granted 143. The Connecticut Superior Court would grant almost 1,000 divorces before 1800. (p. 108)

The most common reasons for divorce were adultery, cruelty, or desertion. The Russell-Cutter collection contains no clues to the unspecified “sundry acts” cited in this particular document, but it’s telling that, even in 18th-century Massachusetts, “the want of mutual Love & Affection” might be considered grounds for the dissolution of a marriage. I don’t know what happened to James or Hannah after 1735, but I like to think their divorce was a mutual and amicable one.

I was fortunate enough to travel with the Massachusetts delegation to this year’s national competition. The festivities began on the evening of Sunday, June 10, with a rousing opening ceremony on the lawn at McKeldin Library. Imagine thousands of students, parents, and teachers cheering, chattering, and trading pins and you’ll have a good sense of what the opening ceremony was like. The competition got down to business on Monday morning, and while in College Park I had the opportunity to serve as a judge along with more than 300 other historians and other education professionals. Anyone who has ever judged at a history day competition can tell you what an amazing experience this is. I met with many talented and enthusiastic students over the course of the three-day competition. They taught me a great deal about topics as diverse as Levittown, the use of helicopters in the Vietnam War, and Nicola Tesla. Thanks to a very well illustrated project on Civil War hospitals, I also have new appreciation for modern medicine.

I was fortunate enough to travel with the Massachusetts delegation to this year’s national competition. The festivities began on the evening of Sunday, June 10, with a rousing opening ceremony on the lawn at McKeldin Library. Imagine thousands of students, parents, and teachers cheering, chattering, and trading pins and you’ll have a good sense of what the opening ceremony was like. The competition got down to business on Monday morning, and while in College Park I had the opportunity to serve as a judge along with more than 300 other historians and other education professionals. Anyone who has ever judged at a history day competition can tell you what an amazing experience this is. I met with many talented and enthusiastic students over the course of the three-day competition. They taught me a great deal about topics as diverse as Levittown, the use of helicopters in the Vietnam War, and Nicola Tesla. Thanks to a very well illustrated project on Civil War hospitals, I also have new appreciation for modern medicine. began with the best parade I’ve ever seen: a parade of participating students across the floor of the arena. I watched over 2,000 students circle the arena with everything from state flags to inflatable lobsters! Throughout the morning, dozens of students were singled out for awards and special prizes, and the boisterous crowd made sure that each winner was duly appreciated. Prizes were sponsored not only by NHD but by friends of history like the

began with the best parade I’ve ever seen: a parade of participating students across the floor of the arena. I watched over 2,000 students circle the arena with everything from state flags to inflatable lobsters! Throughout the morning, dozens of students were singled out for awards and special prizes, and the boisterous crowd made sure that each winner was duly appreciated. Prizes were sponsored not only by NHD but by friends of history like the

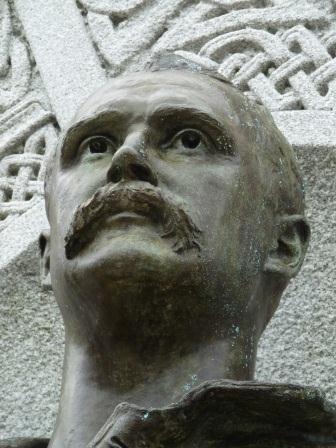

and social activist who brought his passion and patriotism to Boston. He was a giant in the city and won the admiration and respect of all those he met. Upon his death in 1890, thousands of people descended on Tremont Temple to pay their respects.

and social activist who brought his passion and patriotism to Boston. He was a giant in the city and won the admiration and respect of all those he met. Upon his death in 1890, thousands of people descended on Tremont Temple to pay their respects. The figures are placed in front of a backdrop composed of a Celtic cross and Celtic knots carved into the stone.

The figures are placed in front of a backdrop composed of a Celtic cross and Celtic knots carved into the stone.