By Amanda M. Norton, Adams Papers

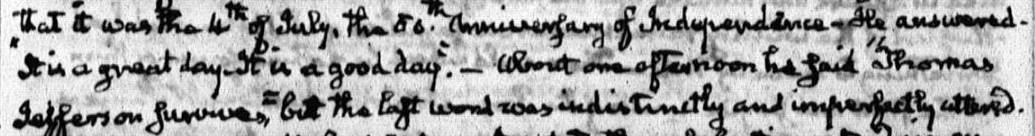

On August 15, 1824, the General Marquis de Lafayette, one of the great heroes of the American Revolution, returned to the United States for the first time in forty years, kicking off a nearly thirteen-month tour of the entire country. After Lafayette’s arrival in Massachusetts, John Adams greeted him via his grandsons on August 22, “There is not a man in America who more sincerely rejoices in your happiness and in the burst of joy which your presence has diffused through this whole continent than myself.” “I would wait upon you in person,” Adams lamented, “but the total decrepitude and imbecility of eighty nine years has rendered it impossible for me to ride even so far as Governor [William] Eustis’s to enjoy that happiness.” He instead requested that Lafayette spend a day with him in Quincy. Lafayette in turn noted his regret that he had not been able to go straight to Quincy “on [his] Arrival at this Beloved place . . . and Embrace You.”

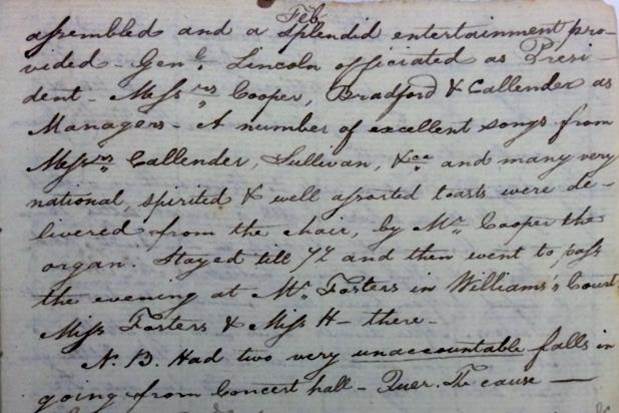

John’s grandson Charles Francis Adams was present for the meeting of the old revolutionaries in Quincy on August 29 and recorded his impressions in his Diary:

The Marquis met my Grandfather with pleasure and I thought with some surprise, because really, I do not think he expected to see him quite so feeble as he is. It struck me that he was affected somewhat in that manner. Otherwise the meeting was a pleasant one. Grandfather exerted himself more than usual and, as to conversation, appeared exactly as he ever has. I think he is rather more striking now than ever, certainly more agreable, as his asperity of temper is worn away. . . . How many people in this country would have been delighted with my situation at this moment, to see three distinguished men dining at the same table, with the reflections all brought up concerning the old days of the revolution, in which they were conspicuous actors and for their exertions in which, the country is grateful! It is a subject which can excite much thought as it embraces the high feelings of human nature. . . . My grandfather appeared considerably affected and soon rose after dinner was over.

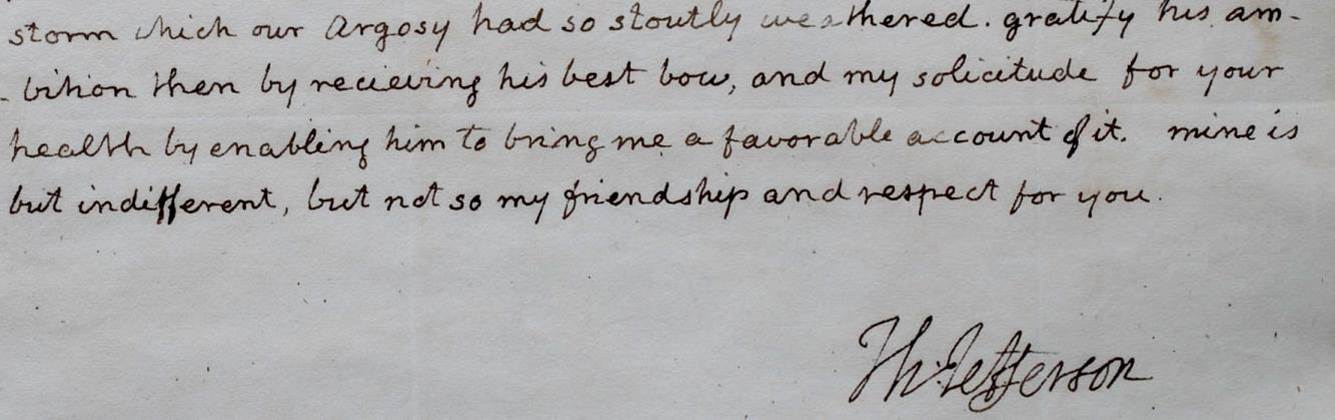

A few weeks after their reunion Lafayette thanked Adams for the visit: “I Have Been Very Happy to See You, and altho’ I Regretted The shortness of My Visit . . . I Have Cordially Enjoy’d, More indeed than I Can Express it, the pleasure to Embrace My old Respected friend and Revolutionary Companion.” A French brass and marble mantle clock that Lafayette gifted to his old friend in honor of this visit now sits in the office of the Editor in Chief of the Adams Papers Editorial Project at the Massachusetts Historical Society.