By Elaine Grublin

Yesterday we shared an Independence Day message from John Quincy Adams on the Beehive. In keeping in the spirit of preparing to celebrate our nation’s birthday, today we share some of John Adams’ words on the subject. In a letter dated 3 July 1776 future president John Adams wrote to his wife Abigail:

The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.

Adams was correct about everything but the date! His description of people using “Bells, Bonfires, and Illuminations” to mark this “most memorable day” is spot on for most American communities today. On Monday, 2 July visit the MHS to hear Stephen T. Riley Librarian Peter Drummey explain why John Adams believed 2 July 1776 would be the most memorable day in the history of America. We will offer two gallery talks, at 10:00 AM and 2:00 PM, for interested visitors to learn the story.

If you cannot make it to a gallery talk, you can still plan to visit the MHS to view the exhibition The Most Memorable Day in the History of America: July 2, 1776. The exhibition, features letters exchanged between John and Abigail Adams, manuscript copies of early drafts of the Declaration of Independence in both John Adams and Thomas Jefferson’s own handwriting, and the Society’s own first printing of the Declaration, also known as the Dunlap broadside. The exhibition is open Monday through Saturday, 10:00 AM to 4:00 PM, from 2 July through 31 August.

Alex Ashlock of WBUR spoke with Peter Drummey about the exhibition over the weekend. Read more in his write-up Should We Be Celebrating July 2nd?

and social activist who brought his passion and patriotism to Boston. He was a giant in the city and won the admiration and respect of all those he met. Upon his death in 1890, thousands of people descended on Tremont Temple to pay their respects.

and social activist who brought his passion and patriotism to Boston. He was a giant in the city and won the admiration and respect of all those he met. Upon his death in 1890, thousands of people descended on Tremont Temple to pay their respects. The figures are placed in front of a backdrop composed of a Celtic cross and Celtic knots carved into the stone.

The figures are placed in front of a backdrop composed of a Celtic cross and Celtic knots carved into the stone.

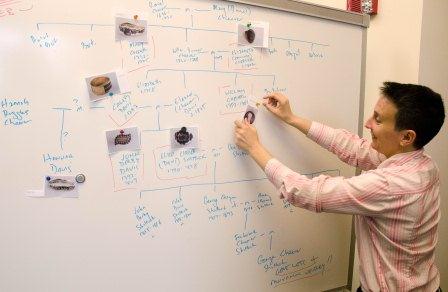

We are working on a book to coincide with the Society’s upcoming exhibition on mourning jewelry. The book, titled In Death Lamented: The Tradition of Anglo-American Mourning Jewelry, features mourning jewels from the Society’s collection and from the private collection of the author, Sarah Nehama.

We are working on a book to coincide with the Society’s upcoming exhibition on mourning jewelry. The book, titled In Death Lamented: The Tradition of Anglo-American Mourning Jewelry, features mourning jewels from the Society’s collection and from the private collection of the author, Sarah Nehama. Just think of the variously colored steeples that dot the campus of Harvard in nearby Cambridge; the golden dome of the State House; and of course, the grand brownstones that line Newbury and Beacon Streets and Commonwealth Avenue. One architectural style that is not well represented in Boston, though, is the Tudor Revival style. And yet, just around the corner from the MHS, among the rows of stone and brick apartment buildings, is a fine example of that style.

Just think of the variously colored steeples that dot the campus of Harvard in nearby Cambridge; the golden dome of the State House; and of course, the grand brownstones that line Newbury and Beacon Streets and Commonwealth Avenue. One architectural style that is not well represented in Boston, though, is the Tudor Revival style. And yet, just around the corner from the MHS, among the rows of stone and brick apartment buildings, is a fine example of that style. A quick look at the building’s exterior shows one repeated feature that hints to its original use: around the building are several large portals — some arched — resembling modern-day garage doors giving the viewer the impression of stables.

A quick look at the building’s exterior shows one repeated feature that hints to its original use: around the building are several large portals — some arched — resembling modern-day garage doors giving the viewer the impression of stables.