By Anne Boylan, Library Assistant

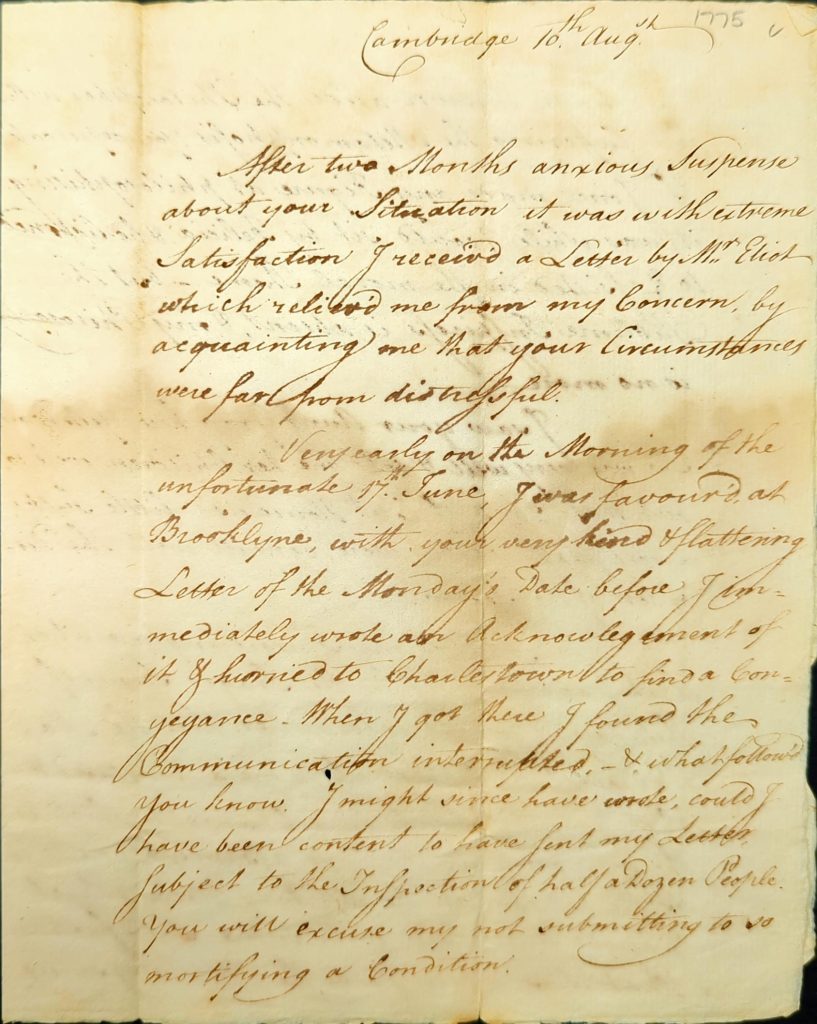

“Parents died when he was 5 ys old. Was bound out. No education of any consequence. Can read but not write. Born in Boston & has lived there and in vicinity most of his life. Work’d at Brickmaking, teaming, &c. &c. Never married. Says he has always work’d hard. First ofence. Been here 2 months. Sentence 9 months.

“Says he has drink’d too freely & that has brot him here. Stole 3 pints of Rum. Wept very freely. Says he can now see his folly and hopes this confinement will be a warning to him. Appears very well.”

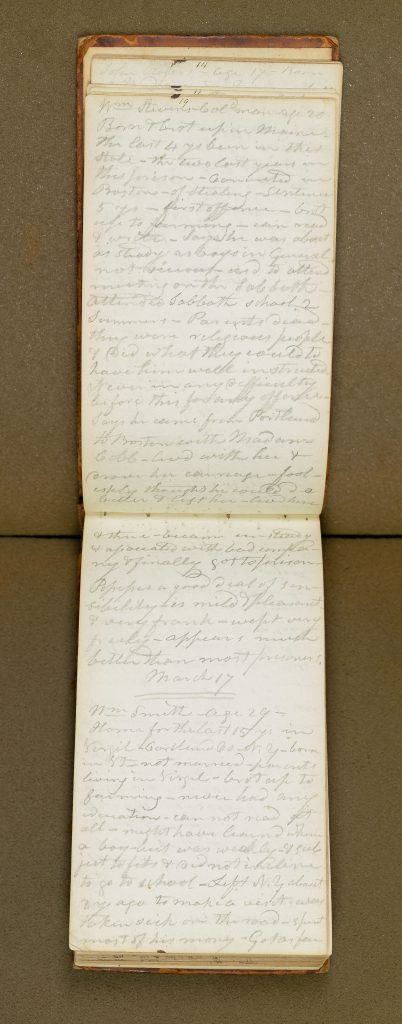

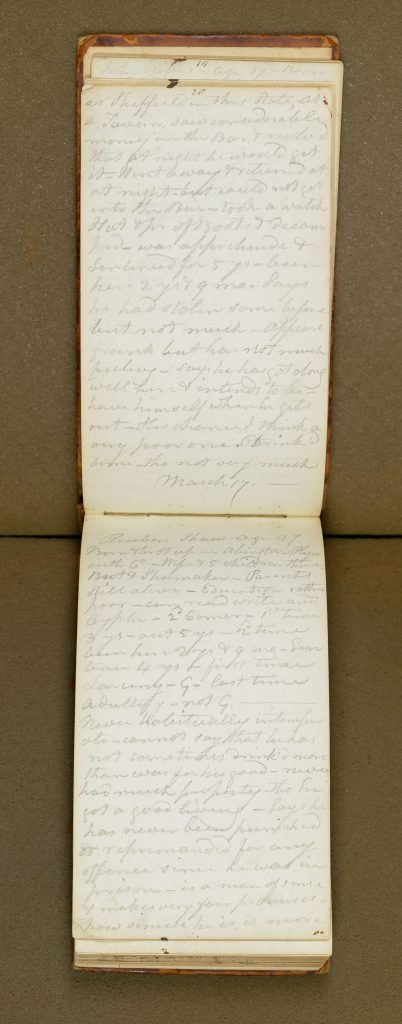

So prison chaplain Jared Curtis described Edward Butler, a 27-year-old inmate at the Massachusetts State Prison in Charlestown, on April 1, 1829. This description and other brief biographical sketches of nineteenth-century incarcerated men fill the Jared Curtis notebooks, 1829-1831, which provide a tantalizingly limited but invaluable view into the lives of populations so frequently excluded from the historical record, such as incarcerated people and, in many cases, the poor, the illiterate, and people of color.

Jared Curtis also recorded these sketches at a particularly pivotal moment in the history of the carceral system. As Philip F. Gura wrote in Buried from the World: Inside the Massachusetts State Prison, 1829–1831, the 1820s saw a shift in the goal of prisons away from punishment and toward reform of the incarcerated. This is not to say that prisons necessarily became kinder or gentler places; this so-called reform was achieved through hard work and extreme isolation, thought to provide the incarcerated person with the proper environment for contemplation and to instill the discipline presumed to have been lacking in their upbringing. While previously, corporal punishment served as both the means and the end of prison, the hard labor and social isolation now became not punishment, but personal improvement. The method, pioneered at Auburn Prison in New York and referred to as “the Auburn system,” prohibited:

“the writing or receiving of letters, even from immediate family. Prisoners could not speak to anyone in prison, even to officers . . . ‘except for purposes of instruction, or to ask for orders and make necessary reports.’” (Gura).

Silent often for the entirety of the day, isolated in their cells at night, prevented even from looking too long at other prisoners, inmates at the Massachusetts State Prison truly were, per Gura’s title, “buried from the world.”

This new emphasis on reform and penance meant that a new marker of success had to be considered to gauge its success: the inmate’s state of mind. Unlike corporal punishment, which exists solely in the physical realm, repentance is internal and can only be intuited and guessed at through outward behavior. Curtis was especially interested in the states of mind of the men whose stories he sketched. He emphasized the sensibility of inmates—not their rationality, as we now use the word to imply—but its contemporaneous meaning, signifying the prisoners’ abilities to understand and be impacted by deep emotion. Curtis felt optimistic about the prospects of Edward Butler, who “[w]ept very freely,” clearly able to access and perform a deep well of emotion under Curtis’s observation. Curtis seemed kindly disposed toward his ability to “see his folly”; his entry hints at an optimism toward Butler’s prospects for rehabilitation.

However, about W[illia]m Smith, 29, Curtis felt very differently: “Says he has stolen some before but not much. Appears frank but has not much feeling. Says he got along well here & intends to behave himself when he gets out. His chance, I think, a very poor one.” Curtis’s poor prognosis for Smith’s moral rehabilitation sits directly adjacent to his observation that he “has not much feeling,” implicitly linking Smith’s ability to feel emotion to his presumed ability to leave criminality behind. These and similar entries raise questions about Curtis’s beliefs in the prospects of his charges that echo forward into the present: can anyone empirically judge another’s moral fiber from their outward demonstrations of emotions? What other factors might cloud or impact that judgement? Who can be trusted to hold the power to determine who exhibits enough emotion, and emotion of the correct type, to demonstrate moral character?

Curtis’s notebooks are a rich vein, giving insight not only into the lives of a population otherwise largely forgotten by the official historical record, but also into the rhetorics of sentiment and penance that laid the nineteenth-century foundations for our present-day ideas around criminality, recidivism, and reform. The notebooks would be a fascinating study for those interested in the history of criminal justice and incarceration, religious instruction, and the lives of various underclasses. If you want to view the Jared Curtis notebooks, plan your visit and make an appointment to do so on the MHS website.