by Aaron Peterka, MHS Early Career Scholar Committee & Mentorship Program Member

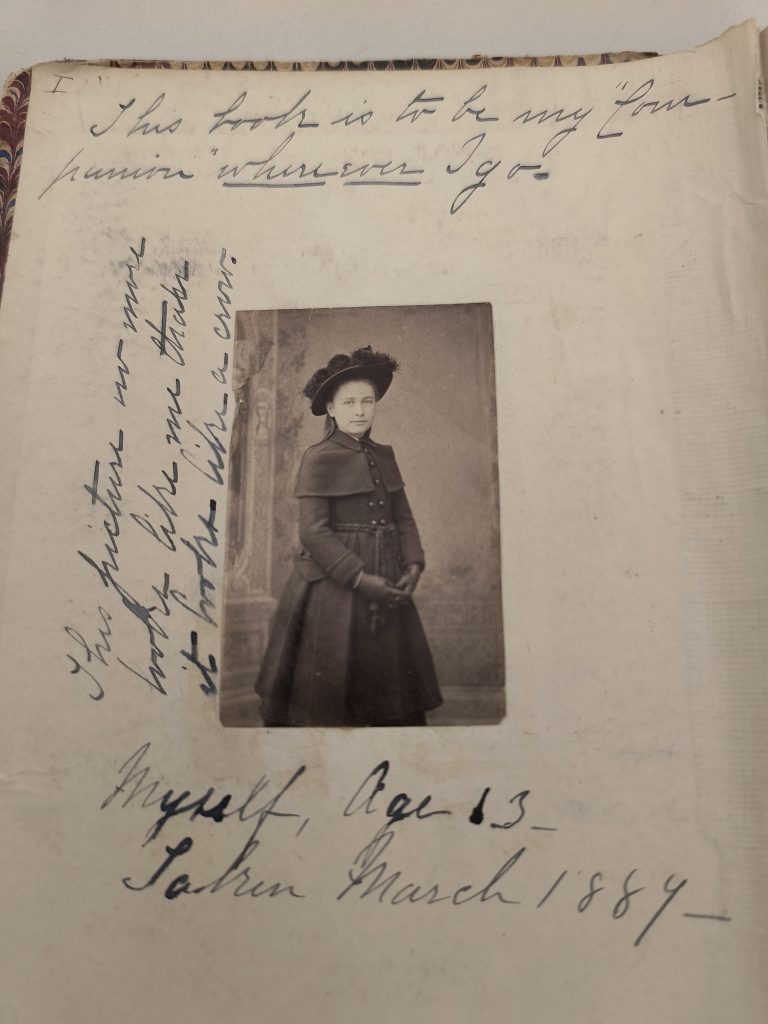

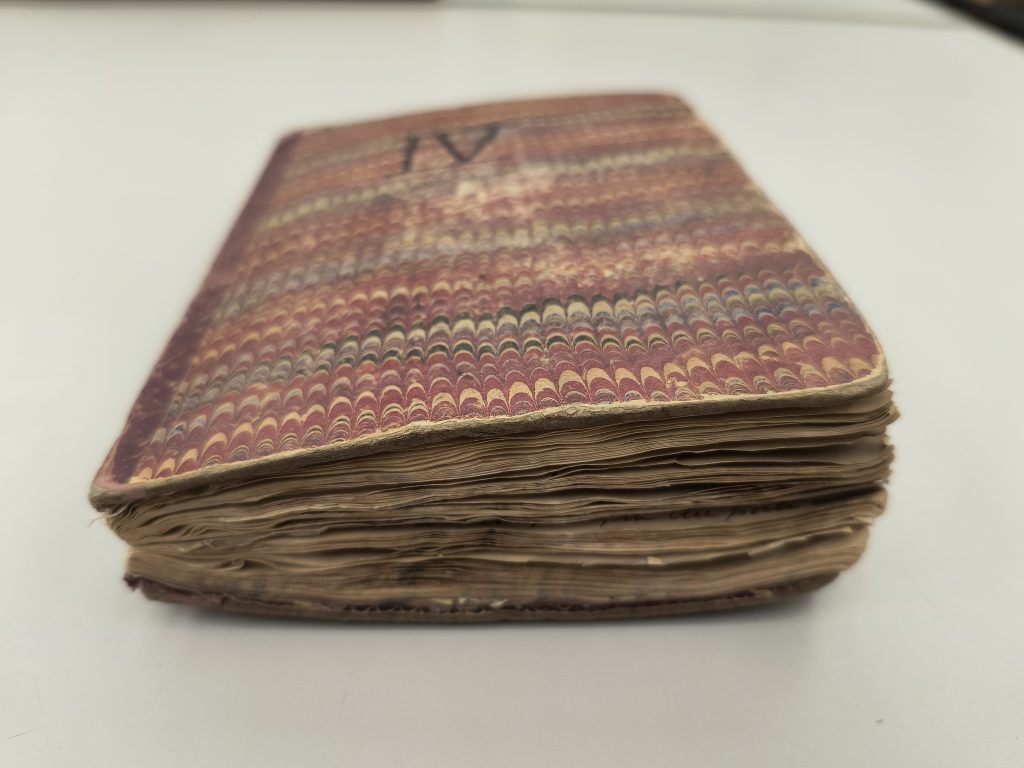

At 95 Waverly Street in Cambridgeport, a silent sentinel still keeps watch. Its four earthen mounds, cradling three eighteen-pound cannons, still face eastward towards Boston, standing at the ready for a long-departed foe from a long-ago war. This is Fort Washington. A relic from the beginning of the American Revolution, this unimposing redoubt is all that remains of the fortifications that besieged the British army in Boston from April 1775 to March 1776. As the country marks the Revolution’s semiquincentennial anniversary, it is all together appropriate to reflect upon Fort Washington and its testimonial to the perilous origins of an army and the embryonic country for which it fought.

Courtesy of Aaron Peterka.

Courtesy of Aaron Peterka.

Fort Washington’s service began on a simple piece of paper upon which General George Washington penned a letter to Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Reed on November 27, 1775. When he first arrived in Cambridge that July to take command of the fledgling Continental Army, he found the fortifications woefully inadequate for a siege, with “shallow redoubts on Winter Hill and Prospect Hill,” a “crude abatis on the Boston Road,” a mere trench stretching across Roxbury’s main street, and a single “breastwork on Dorchester Road.” Rightly concerned with such vulnerabilities, the general labored to improve the American defenses through the coming months, and it was under this labor in the fall of 1775 that he informed Reed that he “caused two half Moon Batteries to be thrown up, for occasional use, between Litchmores point to command that pass, & rake the little rivulet which runs by it to Patterson’s Fort.” Washington also commissioned the construction of three other fortifications “between Sewells point, & our Lines on Roxbury Neck” to further reinforce the American lines.

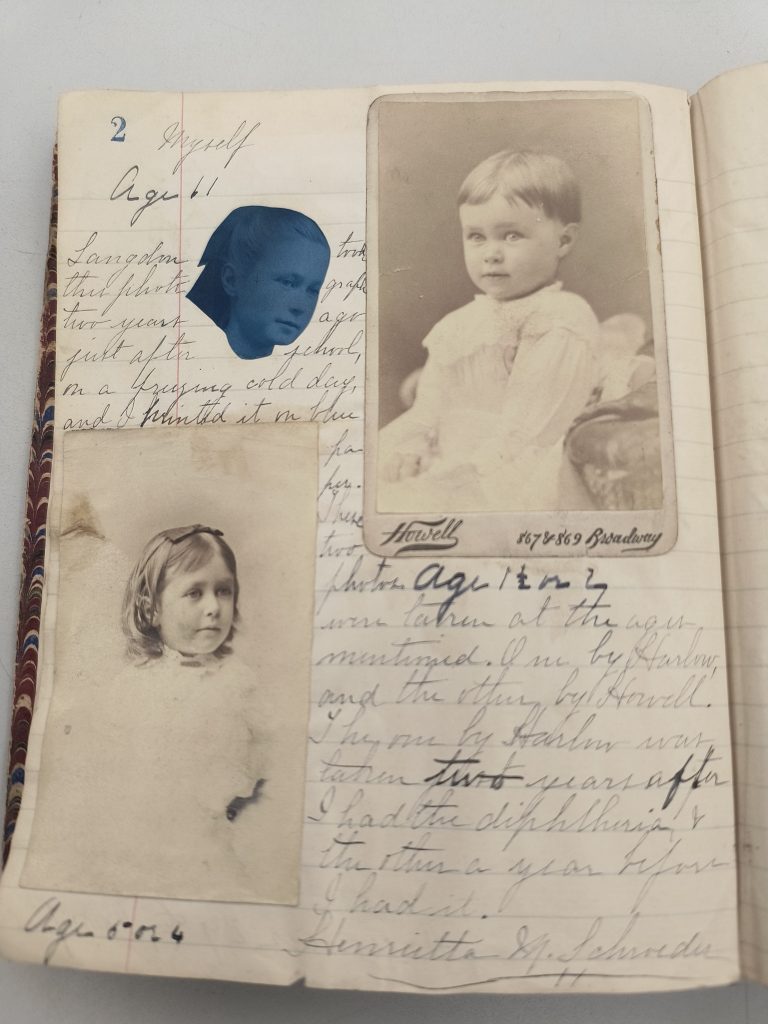

These fortifications are clearly visible on the Henry Pelham Map from 1775 in the Massachusetts Historical Society’s collection, with Fort Washington appearing as the “3 Gun Battery” sitting along the Charles River just before it empties into Boston Harbor. Today, modern Cambridge surrounds the fort, but in 1775, it commanded both the river’s mouth and the southernmost extremity of a meadow that is now part of the MIT campus. This strategic position contributed to Washington’s goal of preventing a British “Sortee, when the Bay gets Froze” and securing Cambridge from attack. Designed to accommodate roughly 50-60 soldiers, the earthen redoubt took the name of the American general-in-chief, its garrison scanning the marshy approaches for any sign of British encroachment. Although there is no record of the fort having ever fired its guns in anger, it nevertheless served an important purpose; a brick in the greater wall that Washington designed to restrict General William Howe’s freedom of movement. And yet, Fort Washington’s service transcends the realm of strategy.

Beyond its military utility, Cambridge’s redoubt gives testament to the harsh realities that confronted the infant American army outside of Boston. In another letter to Reed dated November 28, 1775, Washington conveyed his fears of dwindling gun powder supplies, writing that the vital commodity was “so much wanted, that nothing without it can be done.” Also weighing heavily upon Washington was the omnipresent threat of British spoiling attacks and counter-strikes. Indeed, the general expressed his expectation that the British would interfere with the digging of the “Letchmores point” earthworks, “unless Genl Howe is waiting the favorable moment he has been told of, to aim a capitol blow.”

Facing a growing force of British regulars with an army of untrained civilian-soldiers and his supplies dangerously low, General Washington confided to Reed that had he been able to foresee the dismal state of affairs outside Boston, “no consideration upon Earth should have induced me to accept this Command.” Thus, Fort Washington is both a literal product and reflection of the crisis of 1775, wherein the siege of Boston, even the survival of the Revolution, was in doubt. Erected out of military exigency, the Cambridge earthworks remain a physical reminder that no cause, no revolution, no fight for independence, is ever guaranteed.

Further Reading:

“From George Washington to Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Reed. 27 November 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0401.

“From George Washington to Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Reed. 28 November 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0406.

“Fort Washington,” https://historycambridge.org/Cambridge-Revolution/Fort%20Washington.html.

Robert Middlekauf. The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982.