by Rakashi Chand, Reading Room Supervisor

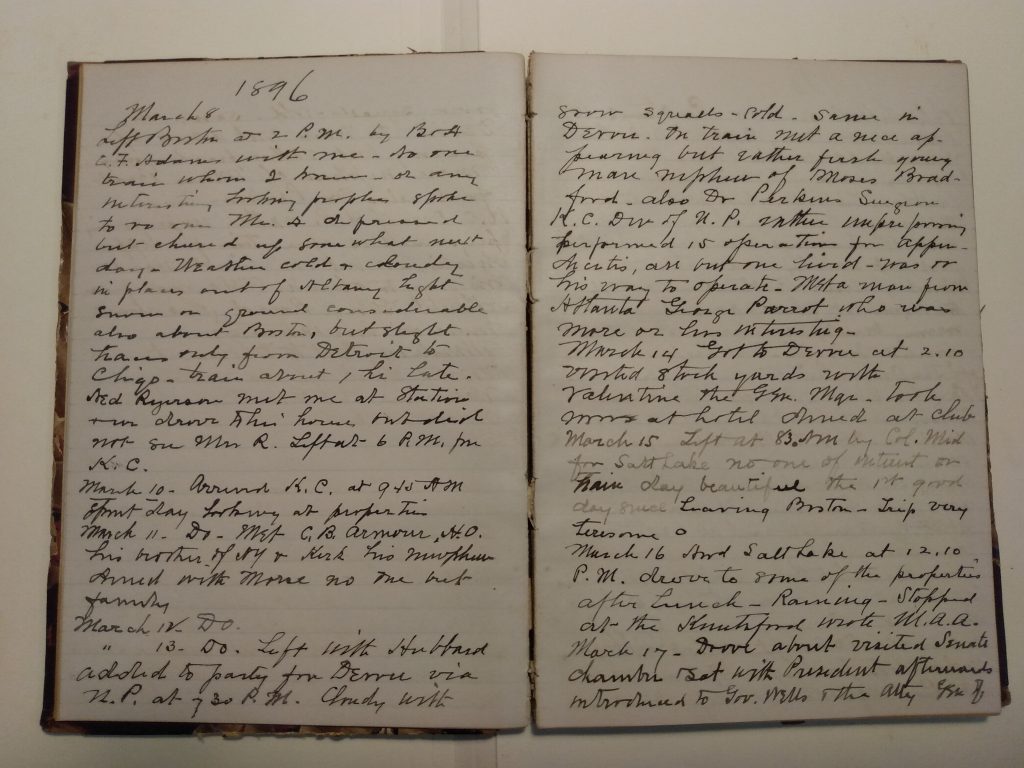

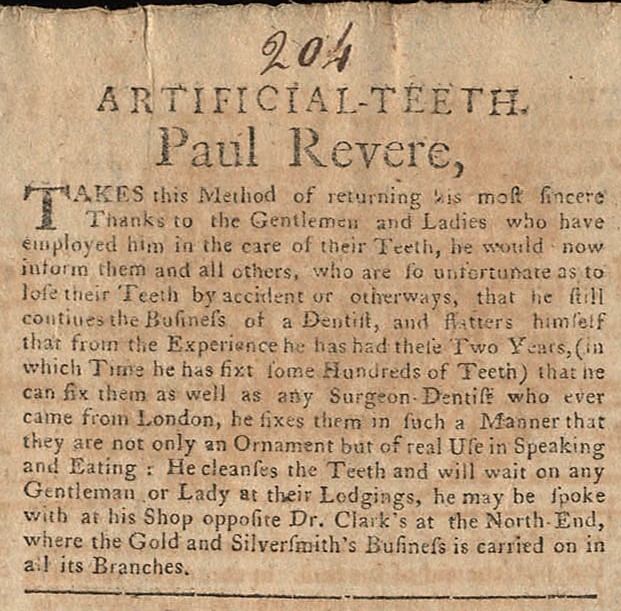

Reality can seem more unbelievable than fiction, as is this tale of the Lincoln love letters. For years there was speculation about a possible romantic interest between Abraham Lincoln and a woman named Ann Rutledge. The evidence was that Ann died suddenly from illness and Lincoln’s first bout with depression soon ensued, however nothing in the historical record linked the two romantically. That changed in 1928, when Wilma Frances Minor presented Ellery Sedgwick, Editor of the Atlantic Monthly, with an opportunity to publish the story of a lifetime… the love affair of Abraham Lincoln and Ann Rutledge based on manuscript letters in Minor’s possession.

Minor was a writer and vaudeville actress from California, who was beautiful, charming, and had almost supernatural powers of persuasion. Sedgwick consulted experts and biographers to authenticate the newly discovered letters Minor presented as family heirlooms, passed down from one generation to the next, and at first, they received validation. Sedgwick invited Minor to Boston, and she charmed all the editors at America’s most reputable literary magazine. The first of three “Lincoln the Lover” series was published, captivating the nation, and providing Minor with a handsome payment.

The ‘lost’ Lincoln letters swept the country, compelling Lincoln biographers and historians to dig deeper into the newly discovered romantic side of Abe which seemed too good to be true.

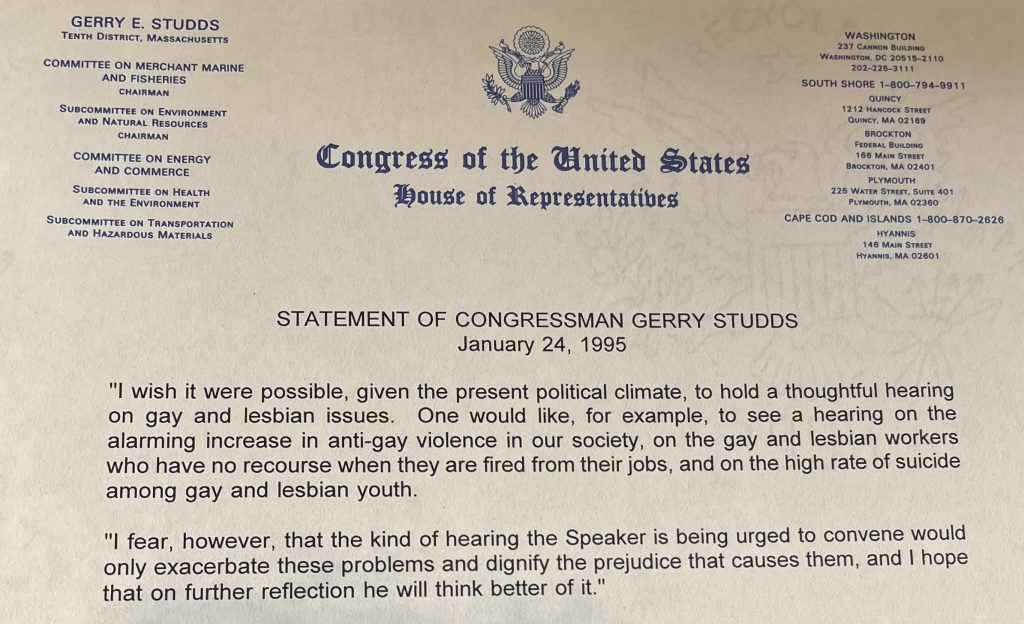

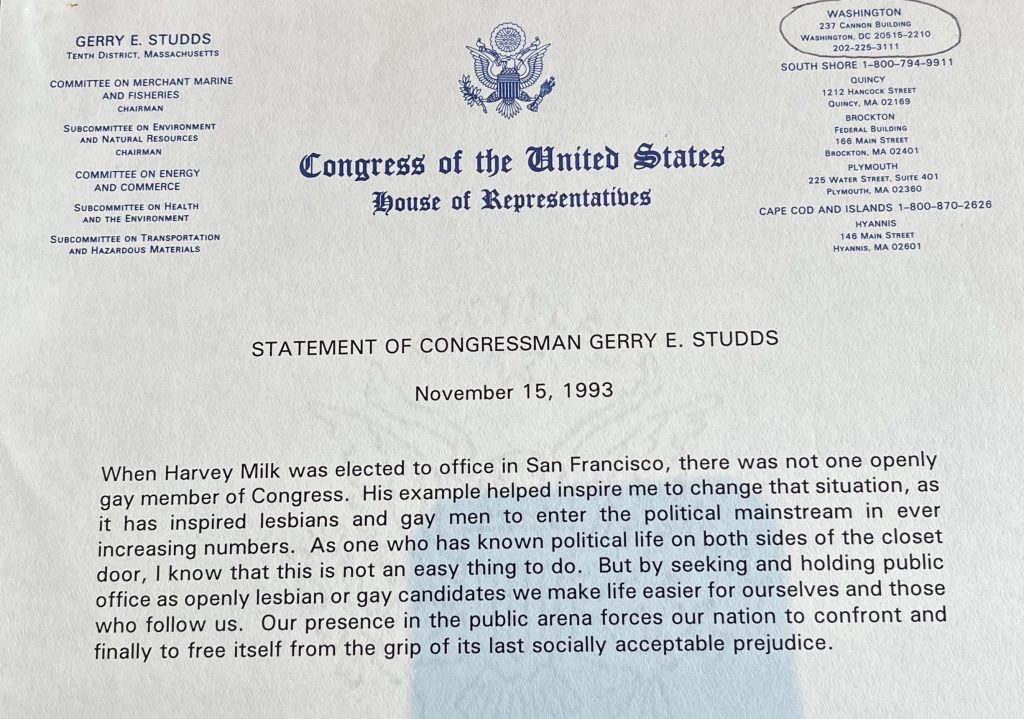

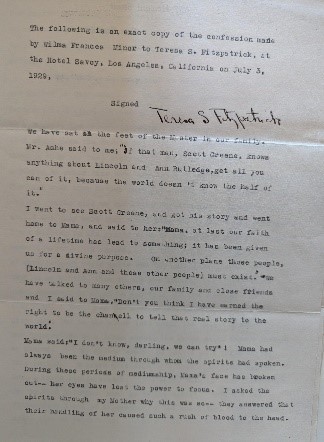

The collection included ten letters written by Lincoln, including three to Ann Rutledge and four to John Calhoun, four letters from Ann Rutledge, including two to Lincoln and several pages from the diary of Matilda Cameron, Ann’s cousin. The provenance of the collection was verified through letters written in various hands, from Frederick W. Hirth of Emporia, Kansas, Minor’s great-uncle, and Minor’s mother, Cora DeBoyer. Sedgwick contacted detective J. B. Armstrong to investigate the case under the supervision of Teresa Fitzpatrick of the Atlantic Monthly staff.

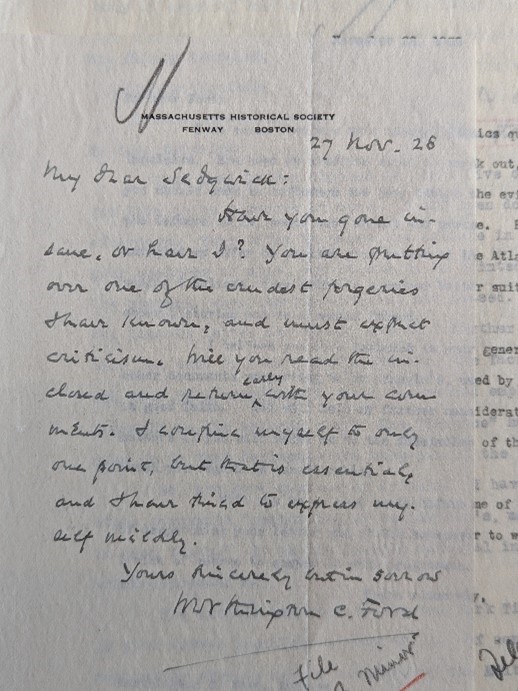

After further speculation, biographers who welcomed the newly found cache of manuscripts noticed discrepancies in style and vocabulary uncharacteristic of the author of the Gettysburg Address. The investigation proved that the letters were forgeries, and the whole affair nothing but an elaborate hoax. The strongest objections to the authenticity of the letters came from the Massachusetts Historical Society’s Editor of Publications, Worthing C. Ford, who wrote to Sedgwick on 24 November 1928, “Have you gone insane, or have I? You are putting over one of the crudest forgeries I have known…”

Scandal! Were these forgeries? Was it a hoax? How had America’s leading literary magazine fallen so completely for a beautiful scam artist and a wishful story?

Minor and her mother confessed to fabricating the letters on 3 July 1929, but with an interesting explanation: Minor claimed that her mother had psychic powers and the spirits of Ann and Abe had urged her to do it… or else the truth about their love would be lost to time. Minor created such a believable and extensive hoax; it simply sends shivers down an archivist’s spine.

“I would die on the gallows that the spirits of Ann and Abe were speaking through my Mother to me, so that my gifts as a writer combined with her gifts as a medium could hand on something worth while to the world.” Page 4 of Wilma Frances Minor’s confession taken by Teresa S. Fitzpatrick on 3 July 1929.

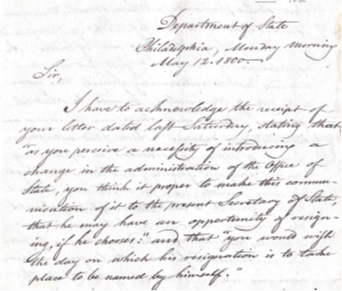

Sedgwick kept the forgeries along with all the correspondence before, during, and after the investigation; including with his staff, with detective Armstrong, with Paul Angle, President of the Lincoln Centennial Association, and many other Lincoln biographers, historians and experts, and finally, with Rumford Press and Little Brown & Co. who were publishing Minor’s book. Also included in the collection is Minor’s book manuscript and the detectives’ reports. The layers of the astonishing affair reveal themselves with each tantalizing page.

Were Minor and DeBoyer simply the vehicle to share a love story that changed the course of American history? Or were Minor and DeBoyer perhaps an incredible team of scam artists who almost succeeded in re-writing history? See for yourself by researching the Ellery Sedgwick Papers housed at the MHS. You can examine the forgeries with your own eyes in the Library at the MHS.

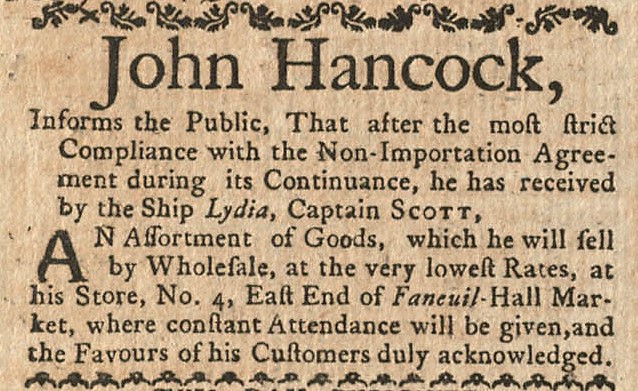

![A Newspaper Advertisement which reads “To be sold by John Hancock, at his store No. 4, at the East End of Faneuil Hall, A general Assortment of English and India Goods, also choice Newcastle Coals and Irish Butter, cheap for Cash. Said Hancock desires those Persons who are still indebted to the Estate of the late Hon. Thomas Hancock, Esq: deceased, to be speedy in paying their respective balances, to prevent trouble. N.B. In the Lydia, Capt. Scott, from London came the following packages 1 W No. 1, A Trunk, No. 2, a small Parcel. The Owner, by applying to John Hancock and saying [illegible], may have his goods."](https://www.masshist.org/beehiveblog/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/John-Hancock-early.jpg)

![Small black and white image of a white man with thinning hair wearing a white shirt with a dark tie. He is wearing large glasses on his face and is frowning.]](https://www.masshist.org/beehiveblog/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Studds.jpg)