By Kittle Evenson, Reader Services

Spring has officially, if tardily, sprung here in Boston and researchers and staff alike are again staring distractedly out of the reading room windows at the green grass, new leaves, and vibrant sunshine.

To draw our wandering attention back inside, I decided to showcase a few examples of early Bostonians preserving and portraying the natural world in all its beauty.

While the MHS offers countless examples of artistic depictions of nature, I chose just two to share here: one for its pure beauty, the other for its scientific bent.

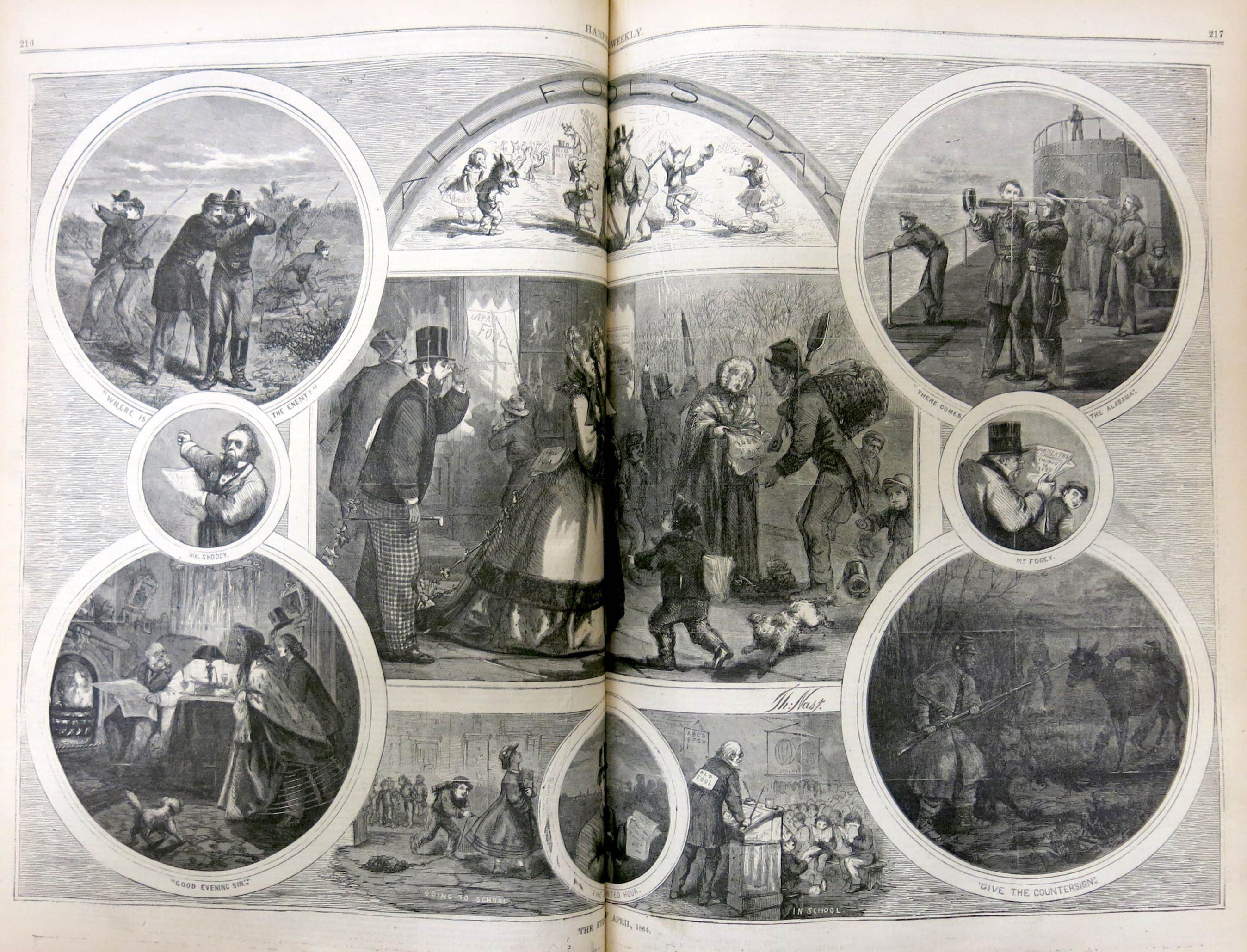

The first is a nondescript volume from the Quincy-Howe family papers. Labeled as “Flower paintings, clippings — Eliza S. Quincy,” and dating to the mid-19th century, the volume is part scrapbook, part sketchbook, with newspaper clippings of familial news mounted opposite hand-drawn sketches of ornate flowers.

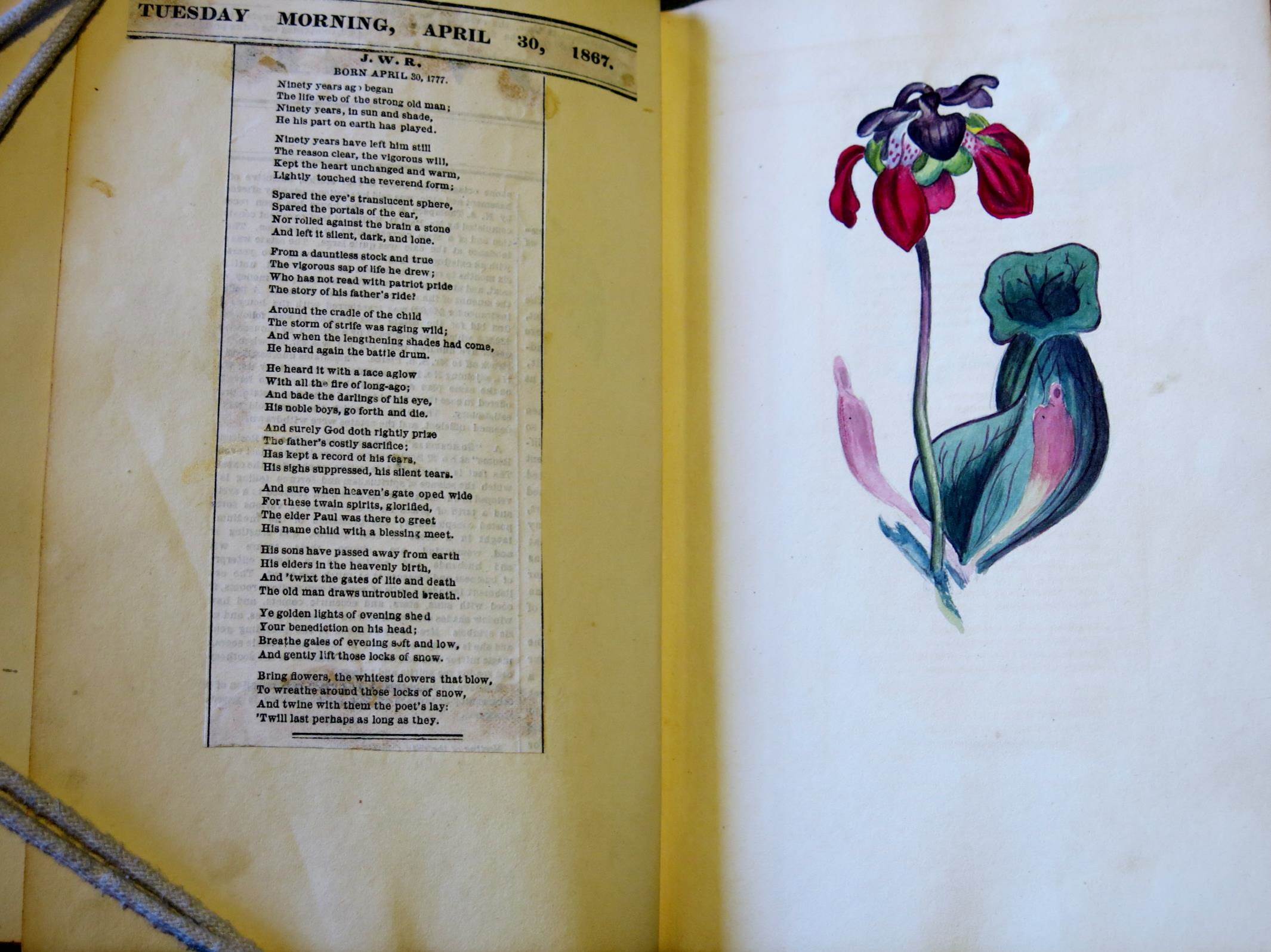

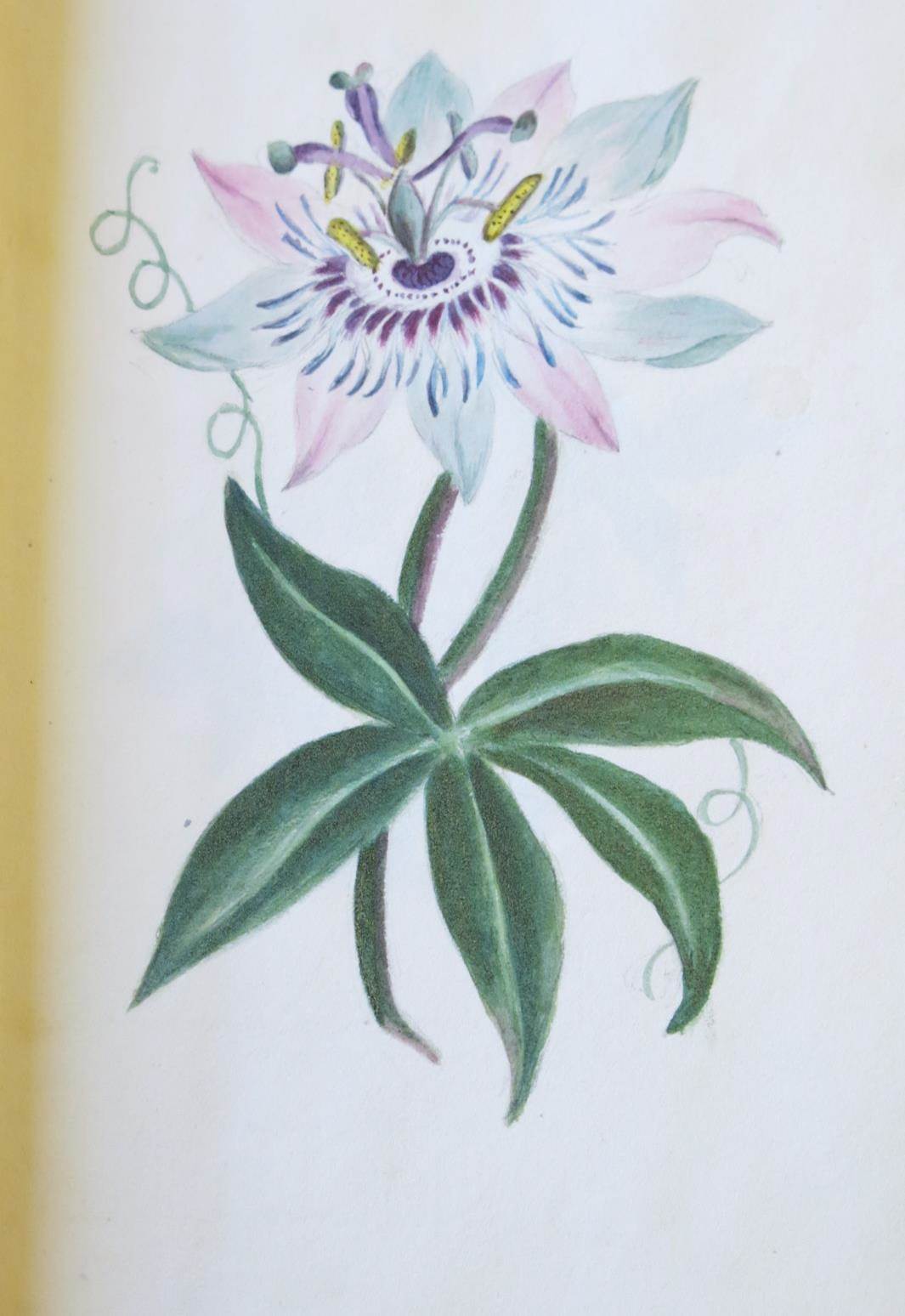

Colorful painting of a flower in Eliza S. Quincy’s 19th century album of flower paintings and clippings

The emphasis of this work is artistic, the mood of the drawings complements the clippings. They are at turns mournful and celebratory, with romantic lines and rich colors.

A painting of a somewhat mournful-looking flower sits opposite a 1867 poem on the life and death of J.W.R.

A delicately-colored painting of a flower in full bloom is unaccompanied by a newspaper clipping

From a similar period (1850s-1870s) the second example is far more scientific, although the beauty of nature is not lost on the viewer (or creator).

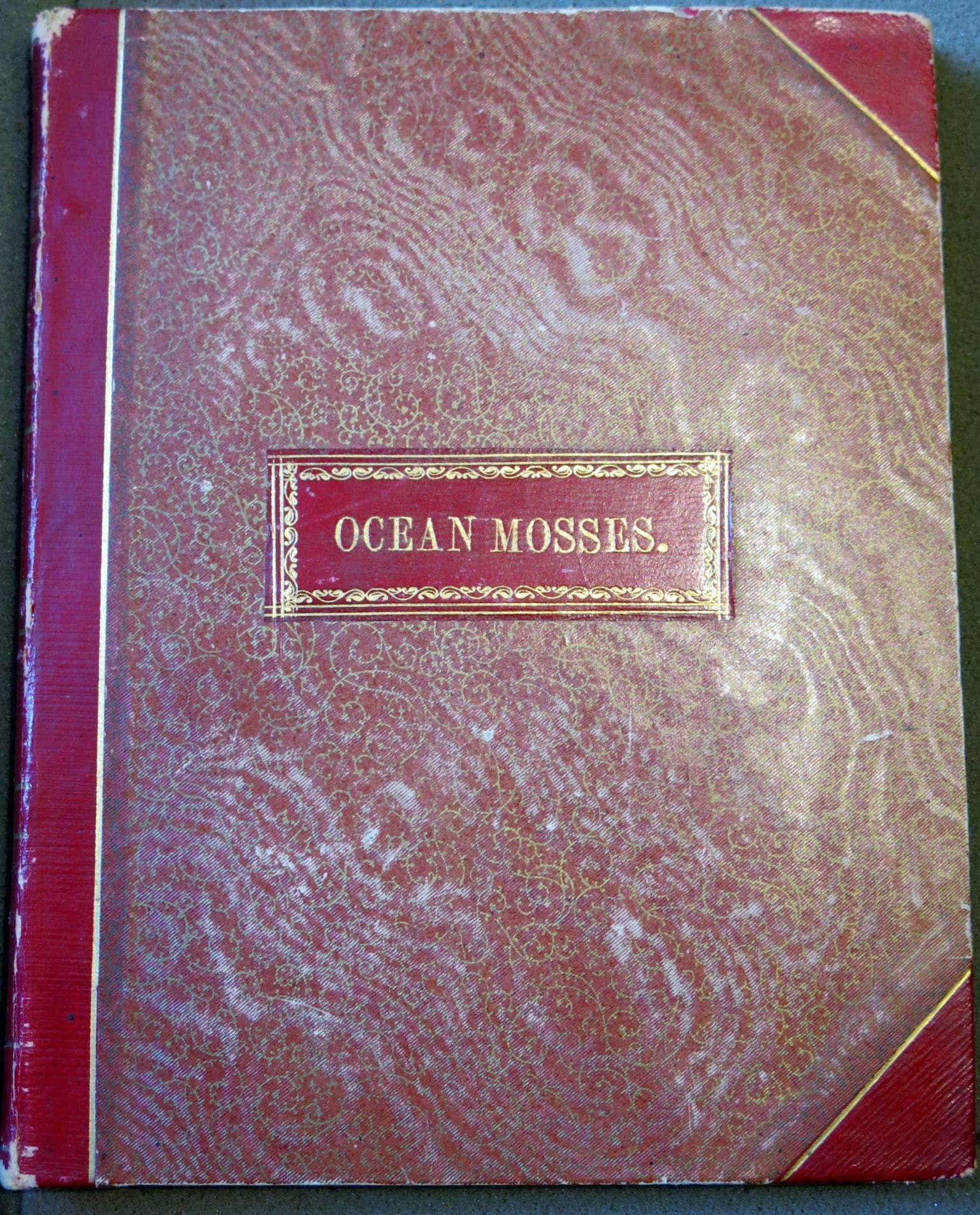

The cover of Ocean Mosses from 1872, owned, if not assembled, by Mrs. Edwin Lamson

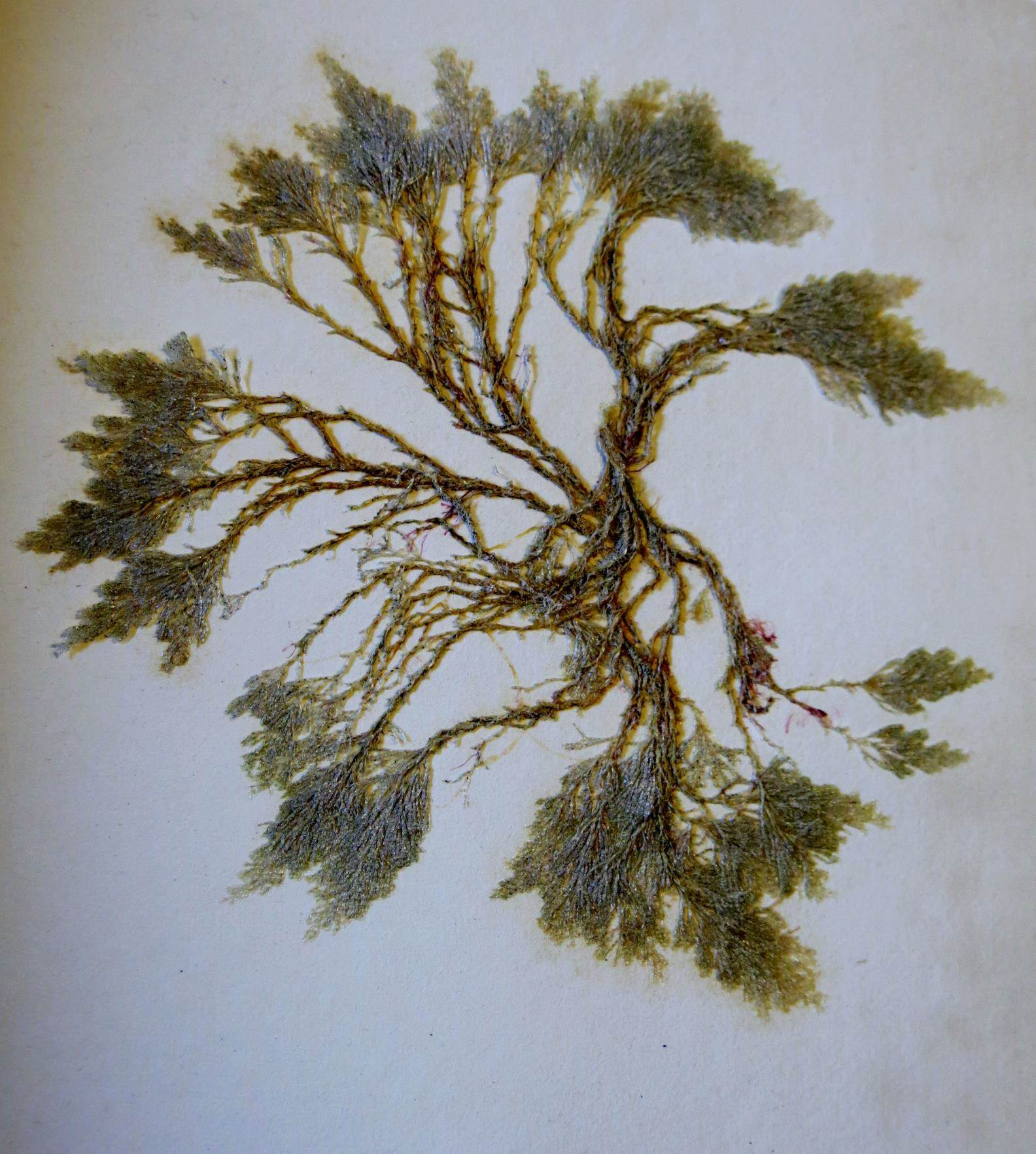

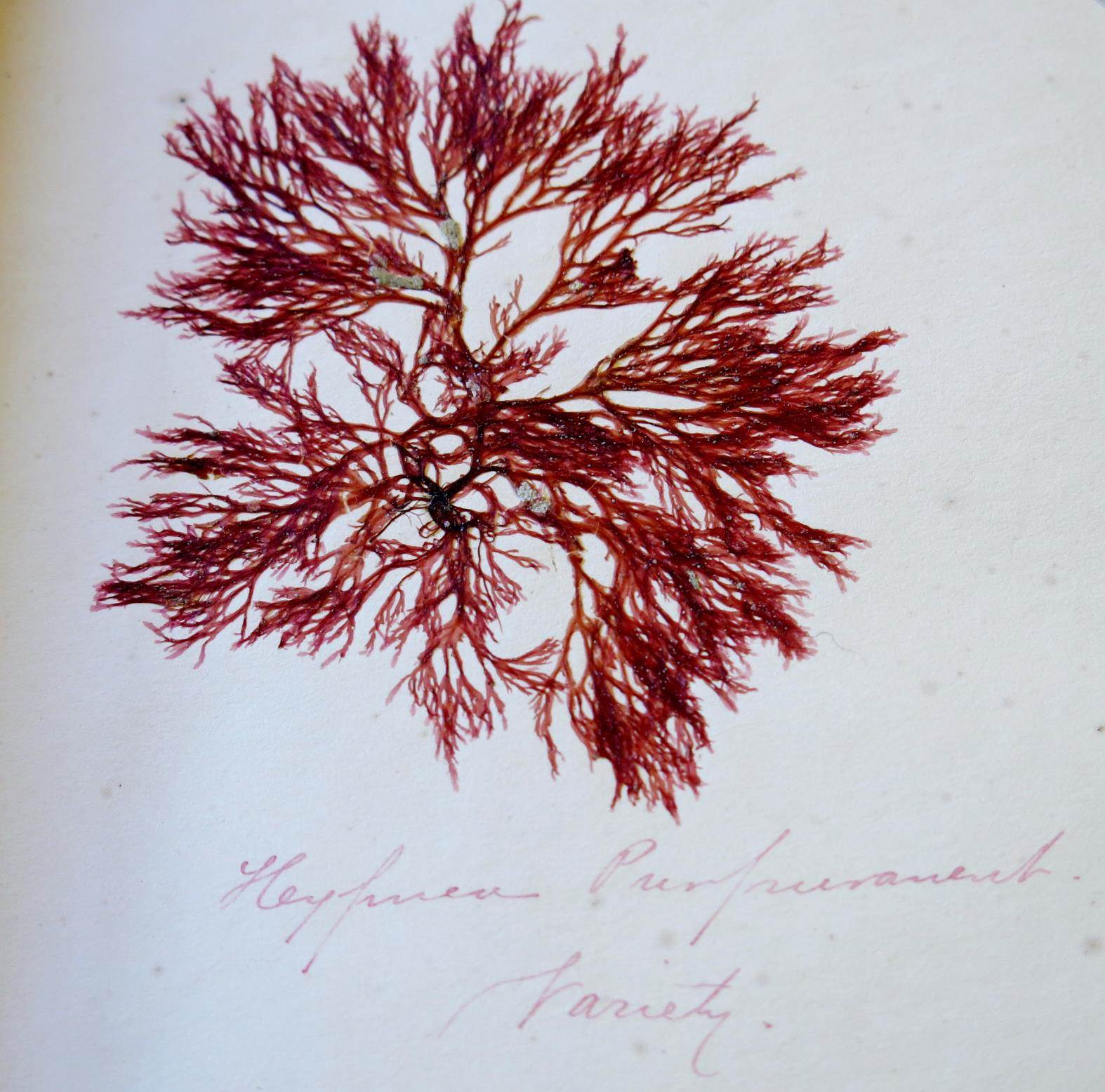

Inside 3 bound volumes from the Lamson family papers are pressed clippings of “ocean mosses” and “ocean flowers” collected along New England coastlines. Some are identified with binomial nomenclature, others are left unlabeled. All are impressively well intact for being approximately one-hundred-and-fifty years old.

An unlabeled segment of ocean moss from a Lamson family volume entitled Ocean Mosses c. 1850

A labeled segment of ocean moss from Mrs. Edwin Lamson’s 1872 volume

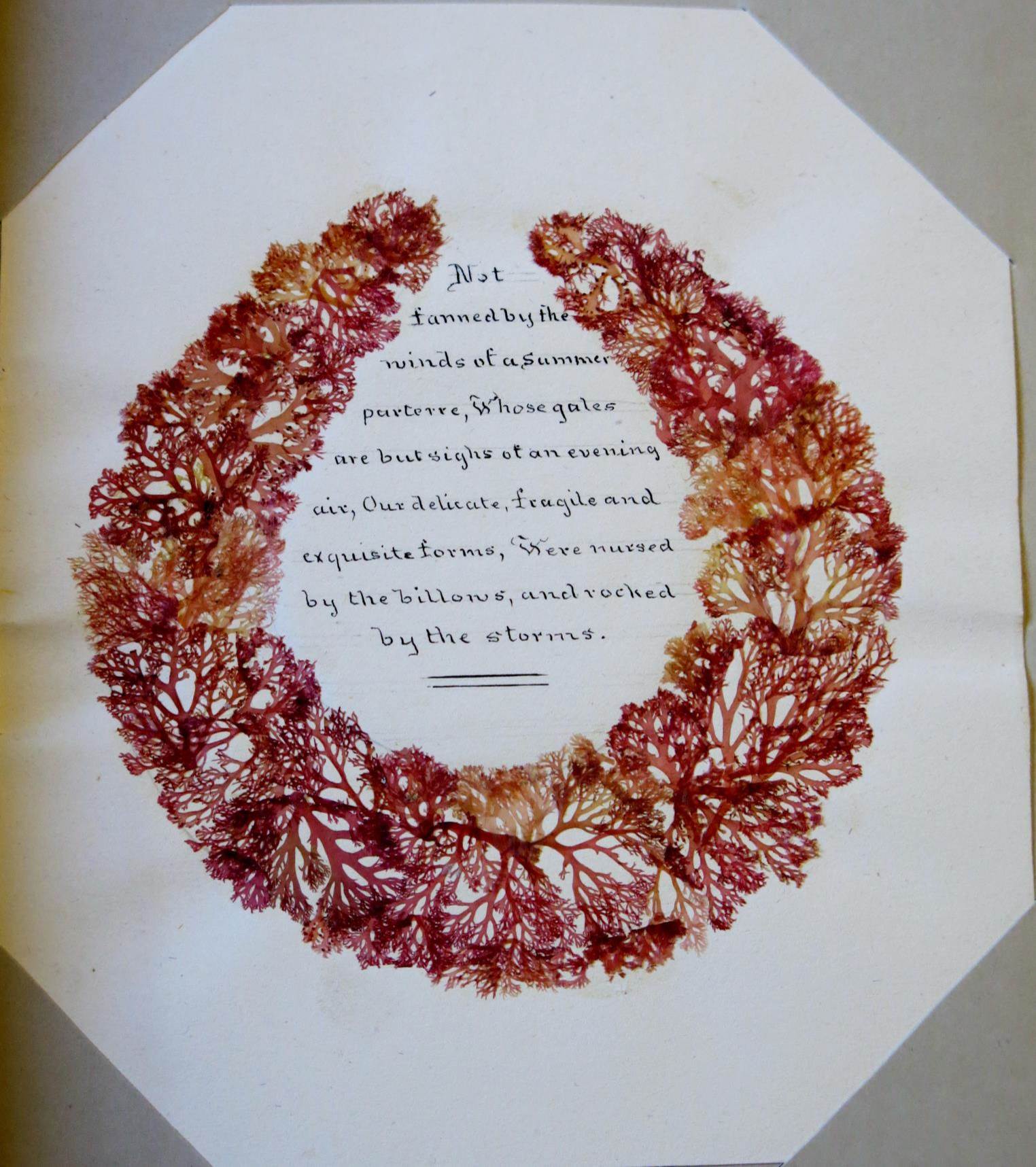

Even though this collection tend towards a more scientific look at underwater nature, the elegance and beauty of these plants prevails.

Artfully arranged ocean mosses surround a poem in Mrs. Edwin Lamson’s June 22, 1872 volume

The poem wreathed by moss reads:

Not

fanned by the

winds of a summer

parterre, Whose gales

are but sighs of an evening

air, Our delicate, fragile and

exquisite forms, Were nursed

by the billows, and rocked

By the storms.

Investigating a bit, this appears to be a slightly modified verse of a longer poem entitled “Seaweeds”:

Oh call us not weeds, but flowers of the sea,

For lovely, and gay, and bright-tinted are we;

Our blush is as deep as the rose of thy bowers,

Then call us not weeds, — we are ocean’s gay flow’rs,

Not nurs’d like the plants of the summer parterre,

Whose gales are but sighs of an evening air;

Our exquisite, fragile, and delicate forms

Are the prey of the ocean when vex’d with his storms

I found several versions of this poem, although few bore official attribution. One version, attributed to a Miss Elizabeth Aveline of Lyme Regis, England, that I found most interesting was mentioned in a book by Patricia Pierce on Mary Anning, an English paleontologist whose early 19th century discoveries of Jurassic marine fossils helped shape our scientific understanding of the world. Pierce mentions how Anning scrawled this poem in an album under a clutch of dried seaweed. An eerily similar description to Lamson’s treatment pictured above.

While I found no reference to Anning amongst the Lamson volumes, this tentative, poetic link piqued my interest in the transatlantic discussions of scientific discoveries had by 19th century women. A topic I am sure to continue exploring.

If 19th century depictions of the natural world strike your fancy and you would like to see these volumes in person, please feel free to stop in and visit our library. If you are interested in seeing what other materials we have related to botany and the beauty of nature you can browse our online catalog, ABIGAIL, from the comfort of your own home.