By Wesley Fiorentino, Reader Services

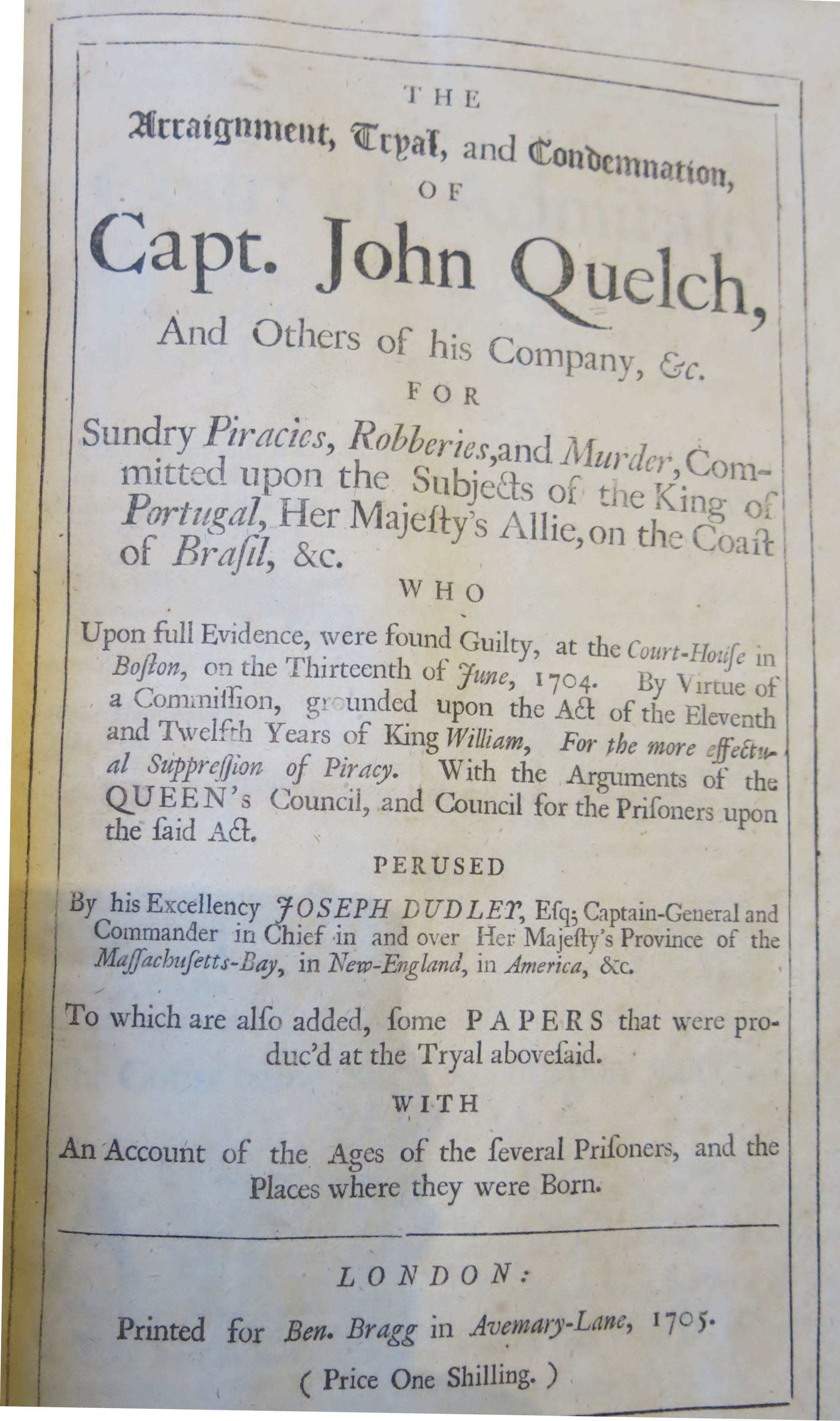

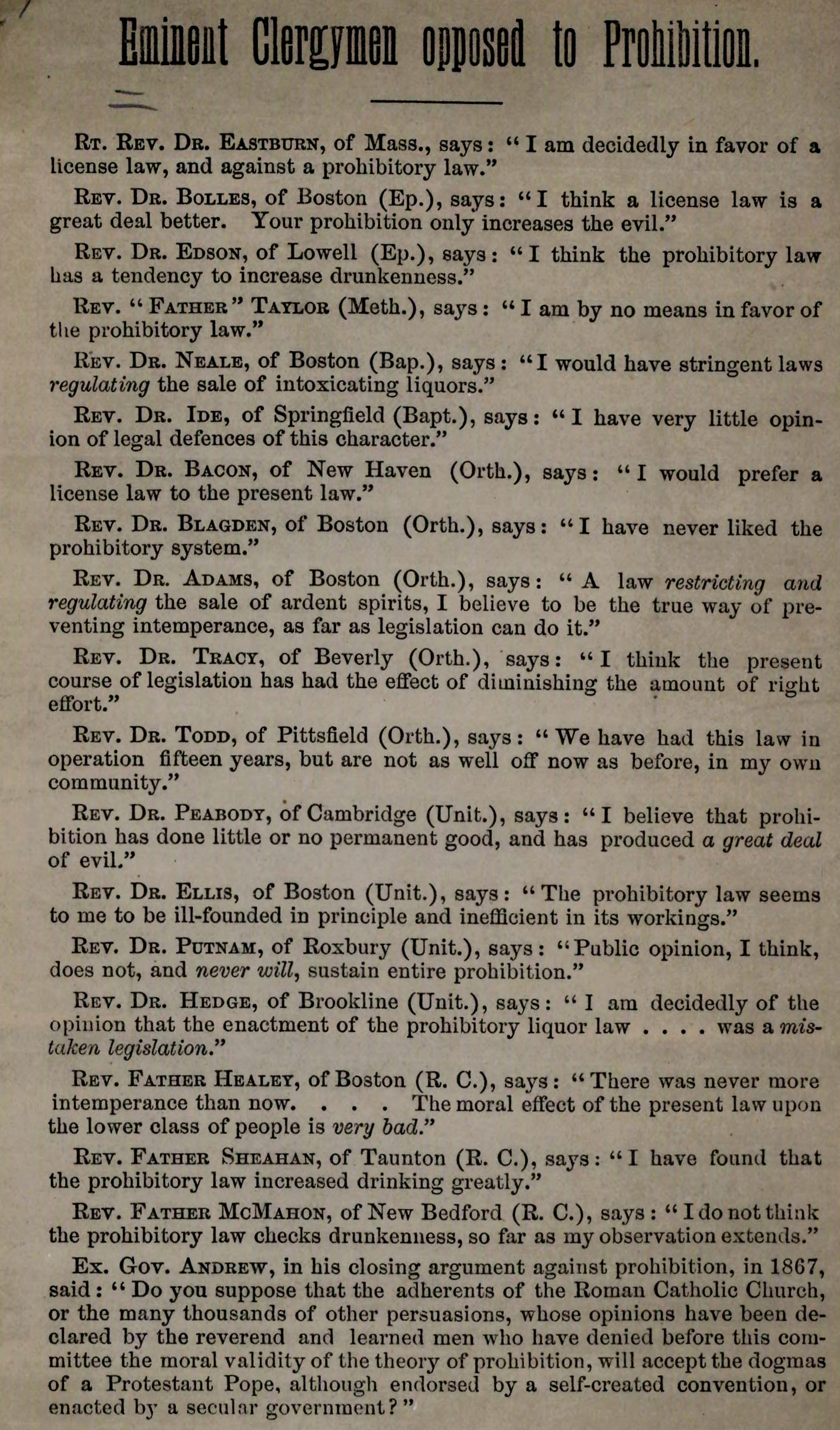

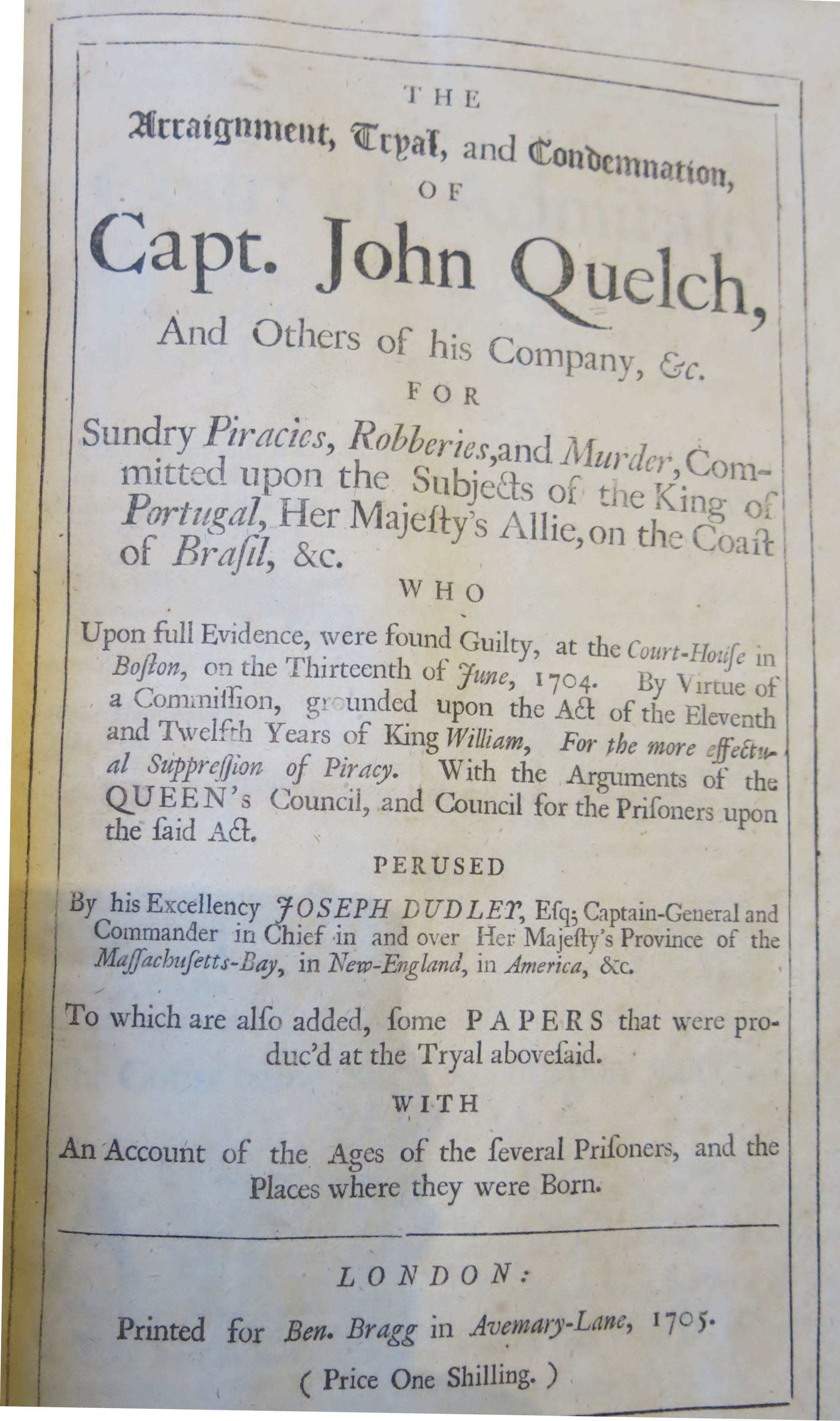

On June 30, 1704, six men were hanged in Boston in what was the first trial for piracy by the British Admiralty Court outside of England.  The Arraignment, Tryal, and Condemnation of John Quelch provides a transcript of what is perhaps Boston’s earliest trial for piracy. The court proceedings provide a detailed account of the events leading up to Quelch’s capture, as well as of the crimes committed Quelch and his crew.

The Arraignment, Tryal, and Condemnation of John Quelch provides a transcript of what is perhaps Boston’s earliest trial for piracy. The court proceedings provide a detailed account of the events leading up to Quelch’s capture, as well as of the crimes committed Quelch and his crew.

In July of 1703, Governor Joseph Dudley granted a privateering license to Captain Daniel Plowman of the Charles and sent the ship to attack French and Spanish vessels near Newfoundland and Arcadia. However, while the ship was still in Massachusetts, Captain Plowman became extremely ill and was confined to his quarters by the rebellious crew. Plowman’s lieutenant, John Quelch, was chosen to be the new captain by the crew and the ship’s course was changed. Plowman was thrown overboard, whether dead or alive seems uncertain, and Quelch led the crew of the Charles on what would be nearly a year-long piracy spree against Portuguese ships in the Caribbean and off the coast of South America.

Between August of 1703 and February of 1704, Quelch and the crew of the Charles attacked and captured no fewer than nine Portuguese vessels off the coast of Brazil, stealing a wide variety of goods and valuables and committing a number of other crimes including murder. Precise dates are given for each of the nine attacks, as well as detailed descriptions of the crimes committed and the goods stolen. The various commodities stolen from the different ships include gold dust, sugar, molasses, rum, rice, textiles, pottery, and a large quantity of coined Portuguese money. Quantities are listed for the goods taken, and values also provided, offering insight into the monetary value of these goods around the turn of the eighteenth century. A value of thirty pounds is given for one of the ships, which had apparently been sunk by Quelch and his crew.

The court record also provides historical information on Africans enslaved both in British and Portuguese colonies during this period. A number of enslaved people of African descent are referred to in the records both as the property of the crew and as plunder from piratical raids. At least three people are referred to in a letter of John Colman, provided in the appendix to the court proceedings, to colonial authorities in the West Indies. Two of them, named Charles and Caesar, are mentioned by Colman as the property of a Colonel Hobbey. The third, named Mingo, is listed as belonging to Captain Plowman himself. Colman mentions the three men in a plea to the colonies of the West Indies to secure the goods on board the Charles and prevent them from being stolen by the mutinous crew. Colman asks for the return of the men “and their shares,” and it is unclear whether this means that Charles, Caesar, and Mingo had any actual share in the goods on the ship, or whether it means the shares of their respective owners.

At least two more enslaved men were captured by Quelch and his crew during several of their attacks on Portuguese ships. Joachim, an enslaved person aboard a Portuguese brigantine taken by the Charles, was valued at twenty pounds. Joachim is described as baptized, possibly as a Catholic given his ownership by a Portuguese master, though this is not expressly stated. He is the only enslaved person in the record described as baptized. Emmanuel, an enslaved person valued by the court record at forty pounds, was the property of a Portuguese commander named Bastian whose ship was captured by Quelch and his crew near the River Plate (Rio de la Plata) in South America. Bastian was shot and killed during the attack, apparently by Christopher Scudamore the ship’s cooper, according to the testimony of Emmanuel. For a time Joachim and Emmanuel served the crew, but were both sold to crew members at some point during the voyage. Joachim was purchased by one George Norton, and Emmanuel was purchased by Benjamin Perkins, both for undisclosed amounts.

During the trial itself, three members of the crew, Matthew Pymer, John Clifford, and James Parrot, testified against Quelch in court and so avoided prosecution. The transcript also repeatedly states that the English and Portuguese crowns had recently become allies at the time of Quelch’s crimes, further exasperating the case against him. Among those presiding over the trial were Governor Joseph Dudley and Samuel Sewall, First Judge of the Massachusetts-Bay Province. John Quelch, John Lambert, Christopher Scudamore, John Miller, Erasmus Peterson, and Peter Roach were sentenced to hang. The execution was carried out “in Charles River; between Broughton’s Ware-house, and the Point.”

Joachim and Emmanuel were both called upon to testify against Quelch and certain members of his crew. Emmanuel specifically identified Christopher Scudamore as the murderer of his master Bastian, while both men testified that Quelch and his crew ordered them to claim that they had been Spanish enslaved people rather than Portuguese upon returning to Boston in order to cover up the crimes against Portuguese ships. Charles, Caesar, and Mingo were all charged with piracy along with the crew, though they were found not guilty. Charles and Caesar were presumably returned to their master, Colonel Hobbey, while the fate of Mingo is not recorded. The fates of Joachim and Emmanuel following the trial are not recorded either. It is interesting to note that though they were considered property, enslaved personswere still called upon to testify in an important trial like free men.

Several important documents and letters are provided in the appendix, including Captain Plowman’s commission from Massachusetts Governor Joseph Dudley as well as his instructions. In the commission, Dudley explains to Plowman that he is “Hereby Authorizing you in and with the said Briganteen and Company to her belonging, to War, Fight, Take, Kill, Suppress and Destroy, any Pirates, Privateers, or other the Subjects and Vassals of France, or Spain, the Declared Enemies of the Crown of England, in what Place soever you shall happen to meet them.” Plowman is warned that “Swearing, Drunkenness and Prophaneness be avoided,” and that no one, even enemies of the British crown, “be in cold Blood killed, maimed, or by Torture or Cruelty inhumanly treated contrary to the Common Usage or Just Permission of War.” Also included are correspondence between Plowman and the Charles’ owners John Colman and William Clarke regarding Plowman’s illness and his growing mistrust of the crew.

Taking place during Queen Anne’s War (1702-1713), the crimes of John Quelch and the crew of the Charles should be viewed in the context of the affairs between the European colonial empires in the New World at the dawn of the eighteenth century. Licensed by Governor Dudley as a “private man-of-war,” the Charles was expressly instructed to attack the ships of “Her Majesty’s enemies,” namely France and Spain. Instead, the crew mutinied against their licensed captain and, to the chagrin of Governor Dudley and British colonial authorities, they attacked the ships of Britain’s ally Portugal. It is clear from the text that these crimes are taken very seriously not only as acts of piracy, but as an embarrassment to the crown.

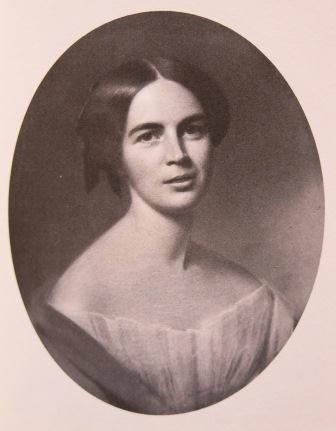

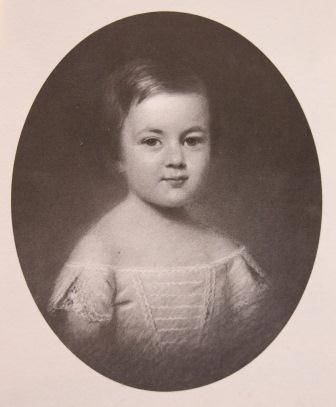

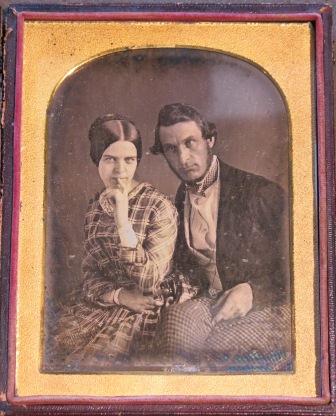

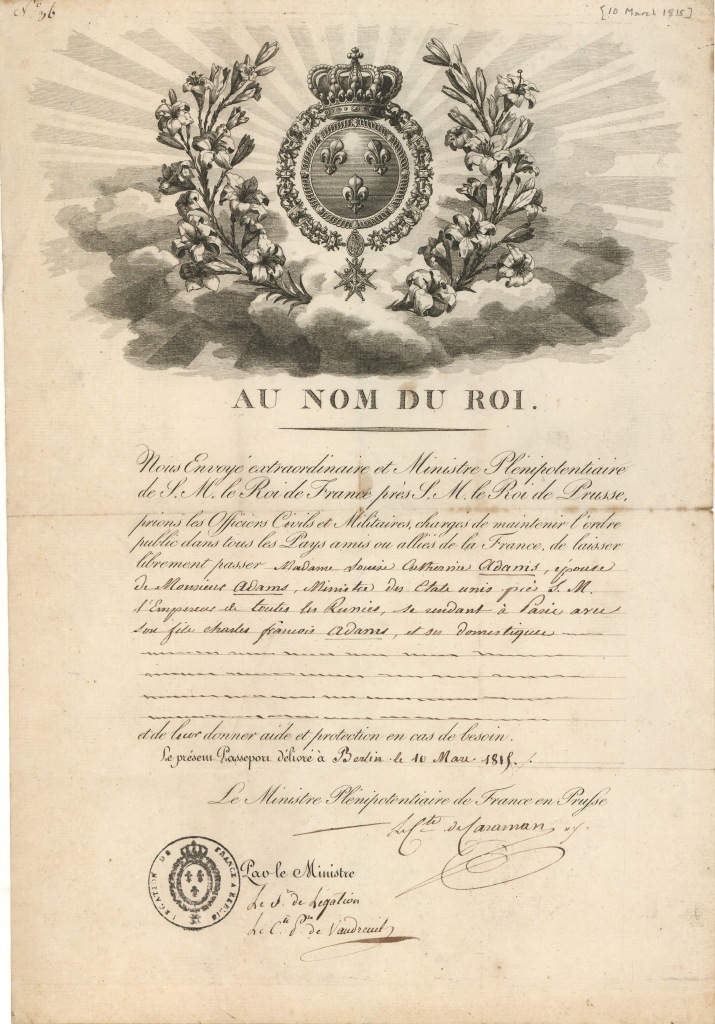

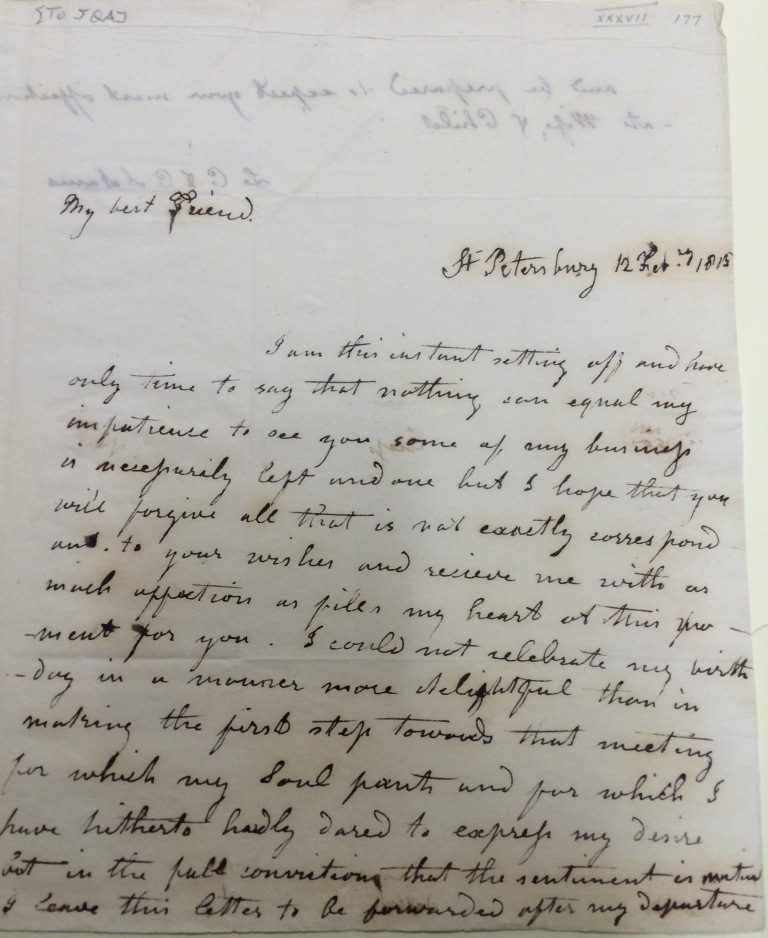

This month marks the 200th Anniversary of Louisa Catherine Adams’s six-week and nearly 2,000-mile trip from St. Petersburg, Russia, to Paris, France. Travelling by carriage across a war-torn Europe and in the midst of Napoleon’s Hundred Days after his escape from his exile on Elba, trying to reach her husband, John Quincy, who, negotiating an end to the War of 1812 in Ghent, she had not seen for a year, Louisa’s story is an amazing one.

This month marks the 200th Anniversary of Louisa Catherine Adams’s six-week and nearly 2,000-mile trip from St. Petersburg, Russia, to Paris, France. Travelling by carriage across a war-torn Europe and in the midst of Napoleon’s Hundred Days after his escape from his exile on Elba, trying to reach her husband, John Quincy, who, negotiating an end to the War of 1812 in Ghent, she had not seen for a year, Louisa’s story is an amazing one. lost carriages, and news of murders on the roads she was travelling. Still she recalled the scenes she passed in her retrospective

lost carriages, and news of murders on the roads she was travelling. Still she recalled the scenes she passed in her retrospective