By Anna J. Clutterbuck-Cook, Reader Services

In my last post, I highlighted the curriculum for a mid-twentieth-century course on “the family” located in the Frank Irving Howe, Jr. Family Papers. The young woman who attended the course was eighteen-year-old Marion Howe, whose diaries from the period elliptically document her questions and anxieties about sexual desire. These diaries, read in counterpoint to the formal curriculum on family life, suggest a hidden curriculum of social constraint that shaped Marion’s experience of her body, her emotions, and the choices she would face in forming adult relationships.

As an adolescent in the newly-constructed American youth culture, Marion’s experience of heterosocial was shaped by the social norms and expectations of her high school peers. Consider these snippets from the winter of 1934:

Johnnie snubbed me, and he and Charlie had another ‘argument.’ Gosh, I don’t know what to do. I like Charlie, I like Johnny, and I like Joe — and I’m in love with one of them, and I don’t know who. I wouldn’t want to give up any of them — Gee, I guess I must be awfully selfish. … I know I’m going to be called a ‘two-timer,’ but what on earth can I do about it? (3 January)

I can’t love Charlie. I might — ! Wotta life! I wrote a note to Johnny, but I haven’t the courage to give it to him. But when I do, I’m gonna ask him if he’s going ‘steady’ with Elie. Gee, how I hate her, even tho’ I don’t know her! (5 January)

Got up rather late after raising Cain in bed with Shrimp and Dutch this morning. … Shrimp and I had a talk last night before going to sleep — and we decided C, J, and I should all have an understanding. … I don’t know what Shrimp means when she says I haven’t learned my lesson yet. (13 January)

I guess I’m fickle, but as long as I’m gonna be an old maid, it’s okay. (23 February)

Charlie came up. Joe asked me if I would go to the movies. Though I liked Johnny. G[eorgie] G[lebus] asked me for a date. Helped prepare Ma’s party at church tomorrow. Cooked 100 or so cakes. (14 March)

As historian Beth Bailey has documented in From Front Porch to Back Seat: Courtship in Twentieth-Century America (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988), mid-twentieth-century youth culture differentiated between dating and “going steady.” Dating was nonexclusive and embedded one’s peer network whereas “going steady” meant exclusivity and a more serious intention to consider engagement or marriage. Yet in practice, where did one slide into the other? It’s clear in these diary entries that Marion is caught up in the pleasure of dating and fantasizing about the relationship potential of the young men who appear to be competing for her attention. Yet she also worries about being read as a “two-timer” for refusing to “give up” Charlie, Johnnie, or Joe. But Johnnie might be “going steady” with Elie — and thus out of bounds for a casual date? Maybe it’s better just to be an “old maid” rather than navigate these uncertain waters.

Dating, and going steady, also meant negotiating physical intimacies — something that Marion expresses a deep ambivalence about. Consider the entry from 1 April 1934:

After church at night Joe and I went for a ride. He let me drive. I’m glad he doesn’t try to get mushy. That’s the greatest trouble of boys of this age. Whenever they take you in their car, they expect you to start petting; and if there’s one thing only in this world that is sickening, it’s petting and the like. (Maybe it’s all right with the right boy.)

Is Marion’s “sickening” displeasure at getting “mushy” due to her own discomfort with relational sex, her disinterest in Joe (whom she will marry two years later), or tension borne of her social role as gatekeeper? It’s impossible to know — likely a combination of all three.

By her late teens, a job-seeking high school graduate whose parents resist her interest in attending college, Marion’s adolescent dating relationships take on a greater degree of seriousness and urgency as the year moves on. In August 1935 she writes of a flirtation with Jim, a lifeguard she has had a crush on, and then a series of entries are cut out of the volume. When the diary resumes, it seems clear she has had some sort of unsettling or violating sexual experience:

Got up about 8. All I could think of was what Jim would be doing. … I’d get thinking of Jim and then lose the sequence of the plot. I hate myself for falling for him. … [her close friend] Shrimp wanted to know more of the Experience Monday, so to oblige her, I told her some of it. The rest she doesn’t know, and so I won’t hurt her. At night it hurts most to remember. And I can’t forget, much as I try. (28 August)

Whatever lessons she has had about human sexuality have not helped her feel confident making sense of her the situation. Several days later, she reports that she’s “had the talk with Shrimp today about generation [and] realize how completely ignorant I have been” (1 September 1935). The details relayed by Shrimp, however, fail to relieve the anxiety she feels about sexual intimacy, and the following spring — shortly after she and Joe commit “the indiscretion” together — she screws up her courage and seeks medical advice:

I went to see a doctor, not so much because I’m afraid but because I am curious, and would like to end this lethal ignorance that always leads to worry. My greatest misery, however, lies in the fact that HE DOESN’T CARE if I worry…

The rest of the entry is ripped out, leaving the question of what constituted Marion’s worries unanswered, though we can make our educated guesses.

Diaries such as Marion’s shed invaluable light on the experience of Depression-era teens exploring their sexuality and emerging adulthood in an era where reliable sexual health information was often difficult to come by — particularly for young women. If you are interested in exploring Marion’s story further, the Frank Irving Howe, Jr. Family Papers are open for research and can be requested from offsite storage by contacting the reference department.

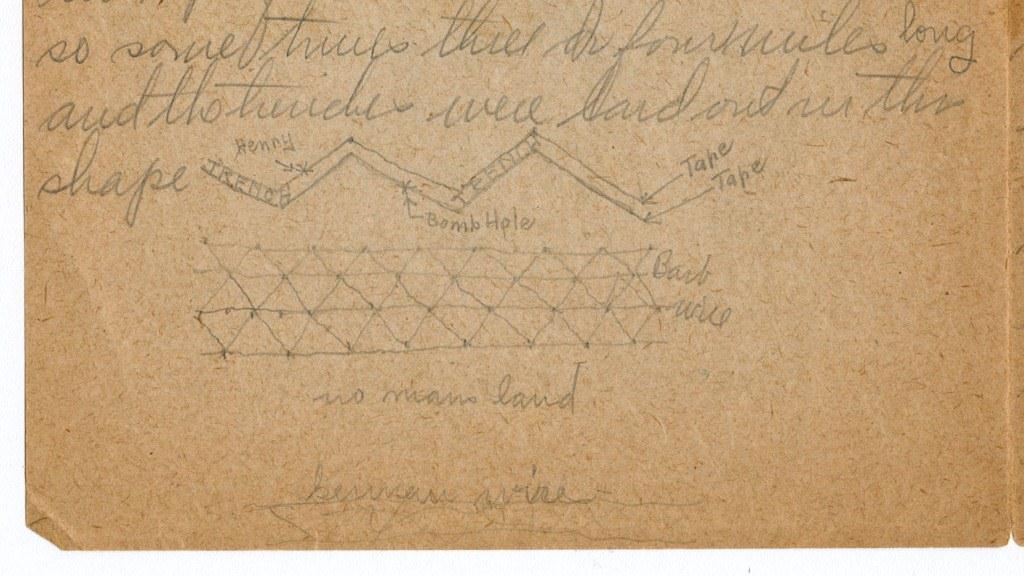

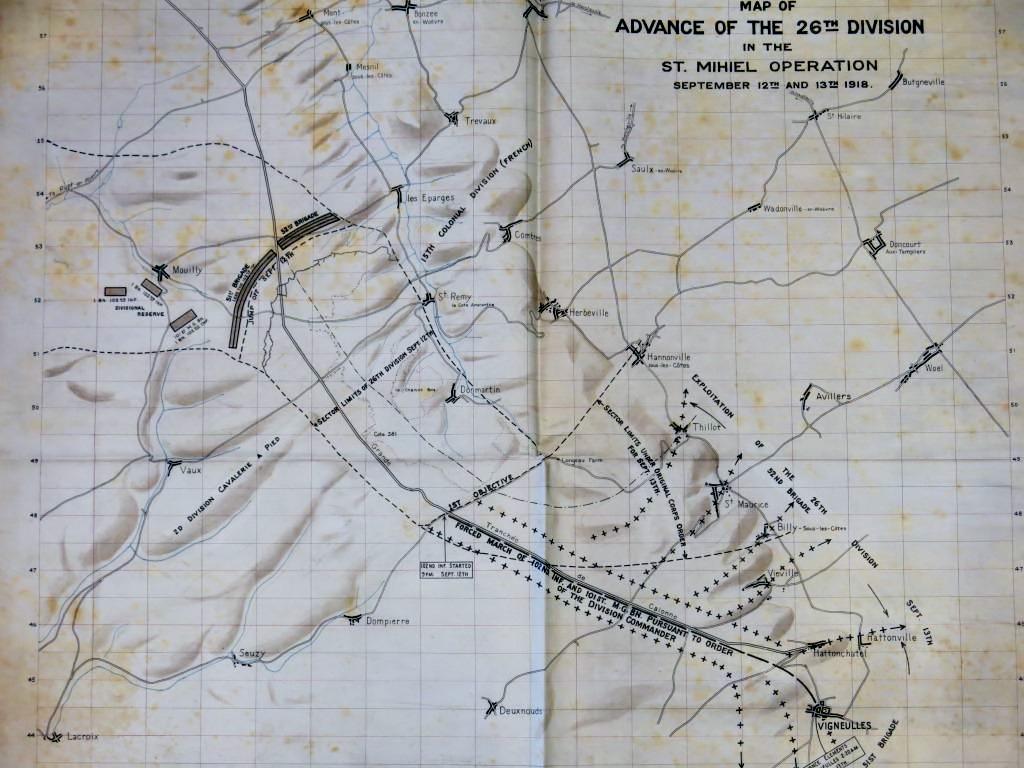

Some of them were written to anxious parents by very young soldiers, barely out of high school and full of bravado. Others come from older, battle-hardened men who write wistfully to their children while shells fall around them. Sometimes a soldier breezily anticipates the upcoming battle in which we know

Some of them were written to anxious parents by very young soldiers, barely out of high school and full of bravado. Others come from older, battle-hardened men who write wistfully to their children while shells fall around them. Sometimes a soldier breezily anticipates the upcoming battle in which we know