By Nancy Heywood, Collection Services

The Massachusetts Historical Society has a collection of 796 newspapers dating from 1765-1776, collected, annotated, and indexed by a Boston man named Harbottle Dorr, Jr. This collection is comprised of 4 volumes containing 3,674 pages. Of that total number of pages, 3,314 are newspapers; 133 are handwritten index pages; and 227 are pamphlets and some introductory pages. Last summer when the MHS purchased volume 4, the collection was finally reunited! Volumes 2 and 3 had been donated to MHS in 1798 and in 1915, the MHS purchased volume 1. Please see the press release describing the exciting acquisition of volume 4 in 2011.

Harbottle Dorr, Jr. (1730-1794) was a shopkeeper, a member of the Sons of Liberty, and served as a Boston selectman for many years (but not all the years) between 1777 and 1791. Beginning in 1765, Dorr spent a dozen years purchasing newspapers, writing comments in margins (as well as inserting reference marks in articles), and assembling indexes. Bernard Bailyn, who wrote the essential essay about the annotated newspapers and their annotator, stated, “Dorr was an ordinary active participant in the Revolution. That is why what he began in 1765 and completed some twelve years later is so extraordinarily revealing.”**

The annotated newspapers convey Dorr’s words and perspective on what he witnessed as a Boston citizen during the years leading up to the American Revolution. The MHS is currently digitizing the annotated newspapers and this project will be completed in early 2013. As we work on the digital project, we’d like to share a few glimpses of Harbottle Dorr, Jr. living and working in Boston.

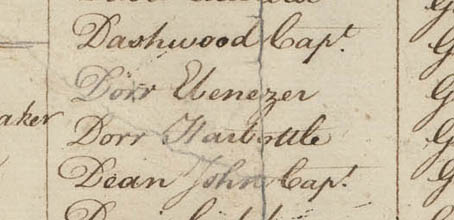

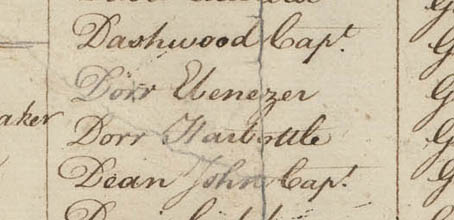

On 14 August 1769, Harbottle Dorr, Jr.  attended a dinner of the Sons of Liberty at Liberty Tree Tavern in Dorchester. A handwritten list by William Palfrey (who eventually became paymaster of the Continental Army during the Revolution), states the names of the 300 men who attended the event. Harbottle’s name appears below Ebenezer Dorr, who was probably Harbottle’s younger brother.

attended a dinner of the Sons of Liberty at Liberty Tree Tavern in Dorchester. A handwritten list by William Palfrey (who eventually became paymaster of the Continental Army during the Revolution), states the names of the 300 men who attended the event. Harbottle’s name appears below Ebenezer Dorr, who was probably Harbottle’s younger brother.

Harbottle’s handwritten introduction to his third assembled volume of newspapers indicates that he worked on his annotation project at his store. Dorr acknowledges that some of his marginalia includes misspelled words “which I hope whoever peruses will excuse, especially as they were wrote at my Shop amidst my business, when I had not leisure to be exact.”

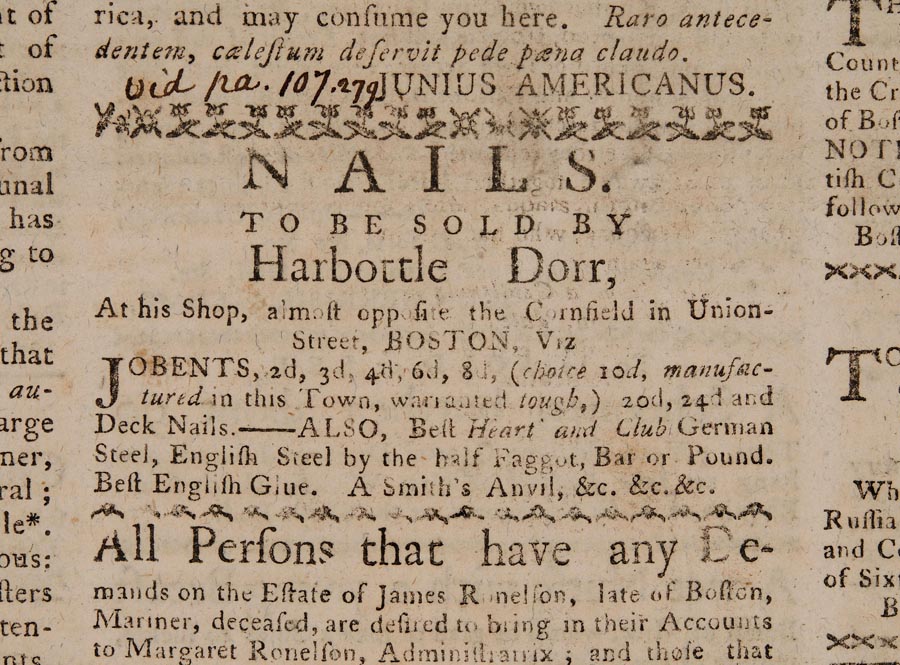

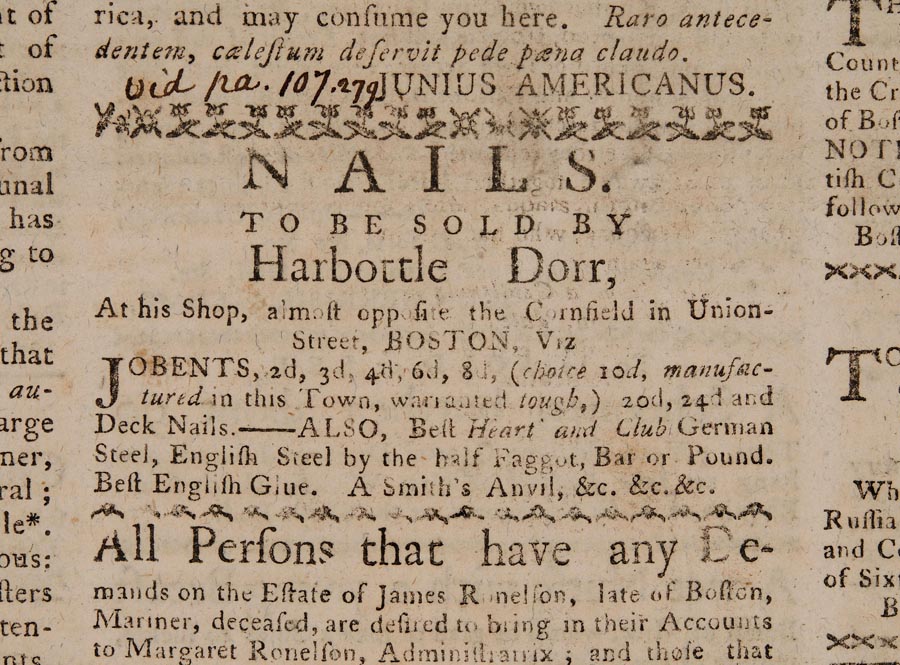

A newspaper advertisement appearing in the 15 January 1770 issue of the Boston-Gazette, and Country Journal (on page 3) indicates that Dorr sold many kinds of nails and different types of steel in his shop located on Union Street. His inventory included jobents (nails used to fasten hinges and/or other thin iron plates to doors and window frames), deck nails (nails used to fasten planks to the decks of ships), German steel, and English steel. These details help us formulate a picture of Harbottle Dorr–at the counter of his shop, surrounded by hardware, with a newspaper open in front of him, writing in the margins in between transactions with customers.

A newspaper advertisement appearing in the 15 January 1770 issue of the Boston-Gazette, and Country Journal (on page 3) indicates that Dorr sold many kinds of nails and different types of steel in his shop located on Union Street. His inventory included jobents (nails used to fasten hinges and/or other thin iron plates to doors and window frames), deck nails (nails used to fasten planks to the decks of ships), German steel, and English steel. These details help us formulate a picture of Harbottle Dorr–at the counter of his shop, surrounded by hardware, with a newspaper open in front of him, writing in the margins in between transactions with customers.

Dorr’s funeral was held on 7 June 1794. The Columbian Centinel from that day included the following notice (on page 3) but didn’t mention the precise date of Dorr’s death:

In this town, Harbottle Dorr, Esq. Æt. 64. A number of years one of the Selectmen of Boston, which he served with honor and integrity. His funeral will be from the house of Mr. Thomas Capen, in Cross-street this afternoon at 5 o’clock, which his relations and friends are requested to attend.

**Bernard Bailyn, “The Index and Commentaries of Harbottle Dorr” in Faces of Revolution: Personalities and Themes in the Struggle for American Independence (NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1990), 85-103.

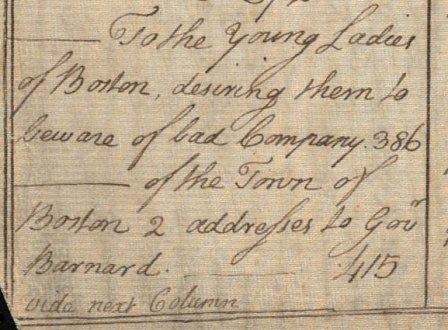

Part of the Harbottle Dorr, Jr. Annotated Newspaper project has been to transcribe and encode for presentation and searching at our website his interesting and detailed indexes. In the process, we took special notice of those subject headings that were quirky, weird, and–to our “modern” sensibilities–humorous.

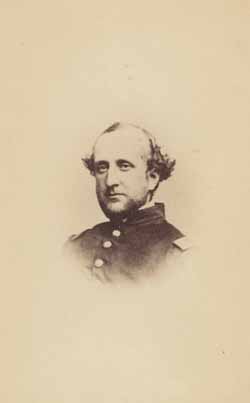

Part of the Harbottle Dorr, Jr. Annotated Newspaper project has been to transcribe and encode for presentation and searching at our website his interesting and detailed indexes. In the process, we took special notice of those subject headings that were quirky, weird, and–to our “modern” sensibilities–humorous. Captain Richard Cary of the Second Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment, the subject of the

Captain Richard Cary of the Second Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment, the subject of the

attended a dinner of the Sons of Liberty at Liberty Tree Tavern in Dorchester. A

attended a dinner of the Sons of Liberty at Liberty Tree Tavern in Dorchester. A  A newspaper advertisement appearing in the 15 January 1770 issue of the Boston-Gazette, and Country Journal (on page 3) indicates that Dorr sold many kinds of nails and different types of steel in his shop located on Union Street. His inventory included jobents (nails used to fasten hinges and/or other thin iron plates to doors and window frames), deck nails (nails used to fasten planks to the decks of ships), German steel, and English steel. These details help us formulate a picture of Harbottle Dorr–at the counter of his shop, surrounded by hardware, with a newspaper open in front of him, writing in the margins in between transactions with customers.

A newspaper advertisement appearing in the 15 January 1770 issue of the Boston-Gazette, and Country Journal (on page 3) indicates that Dorr sold many kinds of nails and different types of steel in his shop located on Union Street. His inventory included jobents (nails used to fasten hinges and/or other thin iron plates to doors and window frames), deck nails (nails used to fasten planks to the decks of ships), German steel, and English steel. These details help us formulate a picture of Harbottle Dorr–at the counter of his shop, surrounded by hardware, with a newspaper open in front of him, writing in the margins in between transactions with customers.