By Elaine Heavey, Reader Services

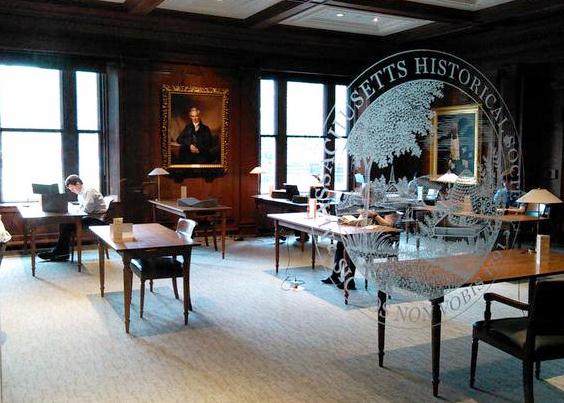

Each year the MHS grants a number of research fellowships to scholars from around the country. For more information about the different fellowship types, click the headings below.

Our various fellowship programs bring a wide variety of researchers working on a full range of topics into the MHS library. If any of the research topics are particularly interesting to you, keep an eye on our events calendar over the course of the upcoming year, as all research fellows present their research at brown-bag lunch programs as part of their commitment to the MHS.

A hearty congratulations to all of the fellowship recipients. We look forward to seeing you all in the MHS library in the upcoming year.

*******

MHS-NEH Long-term Research Fellowships (thanks to the support of the National Endowment for the Humanities, an independent agency of the U.S. government):

Christine Desan

Harvard Law School

“Designing Money in Early America: Experiments in Political Economy (1680-1775)”

Wendy Roberts

SUNY Albany

“Redeeming Verse: The Poetics of Revivalism”

Suzanne and Caleb Loring Research Fellowship On the Civil War, Its Origins, and Consequences (with the Boston Athenaeum):

Robert Mann

“The Contact of Human Souls”

Kevin Waite

University of Pennsylvania

“The Slave South in the Far West: California, the Pacific, and Proslavery Visions of Empire”

MHS Short-Term Research Fellowships:

African-American Studies Fellow

Ben Davidson

New York University

“Freedom’s Generation: Coming of Age in the Era of Emancipation”

Andrew Oliver Fellow

Joseph Lasala

Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies

“Fiske Kimball’s Thomas Jefferson Architect”

Andrew W. Mellon Fellows

Rebecca Brannon

James Madison University

“Did the Founding Fathers Live Too Long?”

Christina Carrick

Boston University

“Among Strangers in a Distant Climate: Loyalist Exiles Define Empire and Nation, 1775-1815”

Travis Jaquess

University of Mississippi

“Founding Daddies: Republican Fatherhood and the American Revolution and Early Republic, 1763-1814”

Benjamin Kochan

Boston University

“Looking East and Thinking Below the Surface: Ecology and Geopolitics in the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries, 1945-2006”

Gregory Michna

West Virginia University

“Facing Outward and Inward: Native American Missionary Communities in New England, 1630-1763”

Scott Shubitz

Florida State University

“Emancipating the American Spirit: Reconstruction and Renaissance in New England, 1863-1877”

Sueanna Smith

University of South Carolina

“African Americans and the Cultural Work of Freemasonry: From Revolution through Reconstruction”

Jordan Taylor

Indiana University-Bloomington

“English Channels: Globalization and Revolution in the Anglophone Atlantic, 1789-1804”

Peter Walker

Columbia University

“The Church Militant: The American Émigré Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1763-92”

Benjamin F. Stevens Fellow

Sarah Templier

Johns Hopkins University

“Between Merchants, Shopkeepers, Tailors, and Thieves: Circulating and Consuming Clothes, Textiles, and Fashion in French and British North America, 1730-1774”

Louis Leonard Tucker Alumni Fellows

Daina Ramey Berry

University of Texas at Austin

“Ghost Values of the Domestic Cadaver Slave Trade”

Amy Hughes

Brooklyn College – CUNY

“An Actor’s Tale: Theater, Culture, and Everyday Life in Nineteenth-Century America”

Margaret Newell

Ohio State University

“Miles to Freedom: William and Ellen Craft and the Struggle for Black Rights in Nineteenth-Century America and England”

Malcolm and Mildred Freiberg Fellow

Karen Weyler

University of North Carolina – Greensboro

“Urban Printscapes: One Hundred Years of Print in the City”

Marc Friedlaender Fellow

Mary Hale

University of Illinois – Chicago

“Fictions of Mugwumpery: The Problem of Representation in the Gilded Age”

Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati Fellow

Katlyn Carter

Princeton University

“Practicing Representative Politics in the Revolutionary Atlantic World: Secrecy, Accountability, and the Making of Modern Democracy”

Ruth R. & Alyson R. Miller Fellows

Alisa Wade Harrison

CUNY Graduate Center

“An Alliance of Ladies: Power, Public Affairs, and Gendered Constructions of the Upper Class in Early National New York City”

Julia James

Syracuse University

“Women in the Woods: War, Gender, and Community in the Native Northeast”

W. B. H. Dowse Fellows

Katie Moore

Boston University

“‘a just and honest valuation’: Money and Value in Colonial America, 1690-1750”

Joanne Jahnke Wegner

University of Minnesota

“Captive Economies: Commodified Bodies in Colonial New England, 1630-1763”

New England Regional Fellowship Consortium (NERFC) Awards (with 21 other institutions; the * indicates that part of fellowship will be completed at the MHS):

Jenny Barker-Devine

Illinois College

“American Athena: Constructing Victorian Womanhood on the Midwestern Frontier”

*Cynthia Bouton

Texas A&M

“Subsistence, Society, Commerce, and Culture in the Atlantic World in the Age of Revolution (1770s-1820s)”

*Jennifer Chuong

Harvard University

The Chargeable Surface: Investment, Interval, and Yield in Early America

Bradley Dixon

University of Texas at Austin

“Republic of Indians: Indigenous Vassals, Subjects, and Citizens in Early America”

*Mehmet Dogan

Istanbul Teknik Universitesi

“From New England into New Lands: The Journey of American Missionaries to the Middle East”

*Andrew Edwards

Princeton University

“Money and the American Revolution”

Michele Fazio

UNC at Pembroke

“The Case of Sacco and Vanzetti and the Italian American Family: Immigrant Women’s Roles Redefined”

Mary Freeman

Columbia University

“Letter Writing and Politics in the Campaign Against Slavery in the United States, 1830-1870“

Jeffrey Gonda

Syracuse University

“No Crystal Stair: Black Women and Civil Rights Law in Postwar America”

Cynthia Greenlee

Duke University

“The Fruits of Our Race: African-Americans and the Politics of Abortion, 1860-1975”

Amy Hughes

Brooklyn College – CUNY

“An Actor’s Tale: Theater, Culture, and Everyday Life in Nineteenth-Century America”

*Kathryn Lasdow

Columbia College

“Spirit of Improvement: Construction, Conflict, and Community in Early National Port Cities”

Rebecca Rosen

Princeton University

“Making the Body Speak: Anatomy, Autopsy, and Testimony in Early America, 1639-1790”

Elizabeth Sharrow

University of Massachusetts

“Forty Years ‘On the Basis of Sex’: Title IX, the ‘Female Athlete,’ and the Political Construction of Sex and Gender

Amy Sopcak-Joseph |

University of Connecticut

“The Lives and Times of Godey’s Lady’s Book, 1830-1877”

David Thomas

“Temple University

The Anxious Atlantic: Revolution, Murder, and a “Monster of a Man” in the Eighteenth-Century British Atlantic World.”

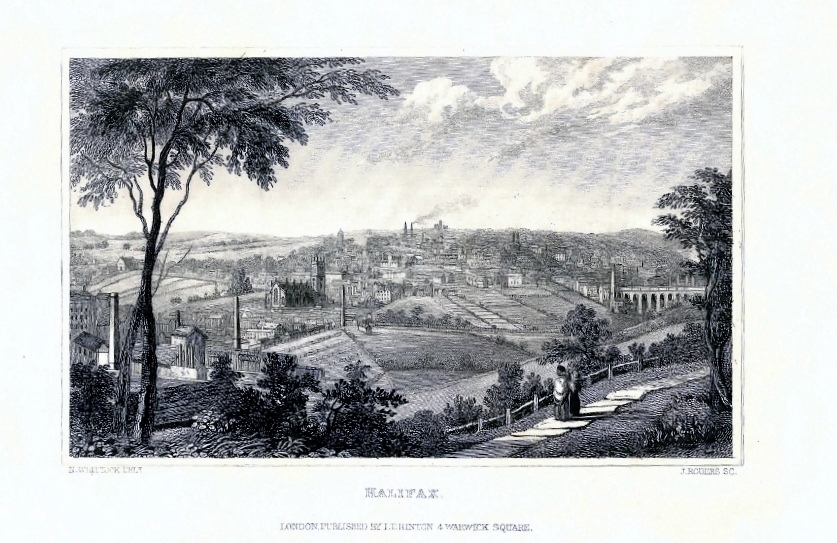

*Emily Torbert

University of Delaware

“Going Places: The Material and Imagined Geographies of Prints in the Atlantic World, 1770-1840”

*Michael Zakim

Tel Aviv University

“Inventing Industrial America at the Crystal Palace”