By Susan Martin, Collection Services

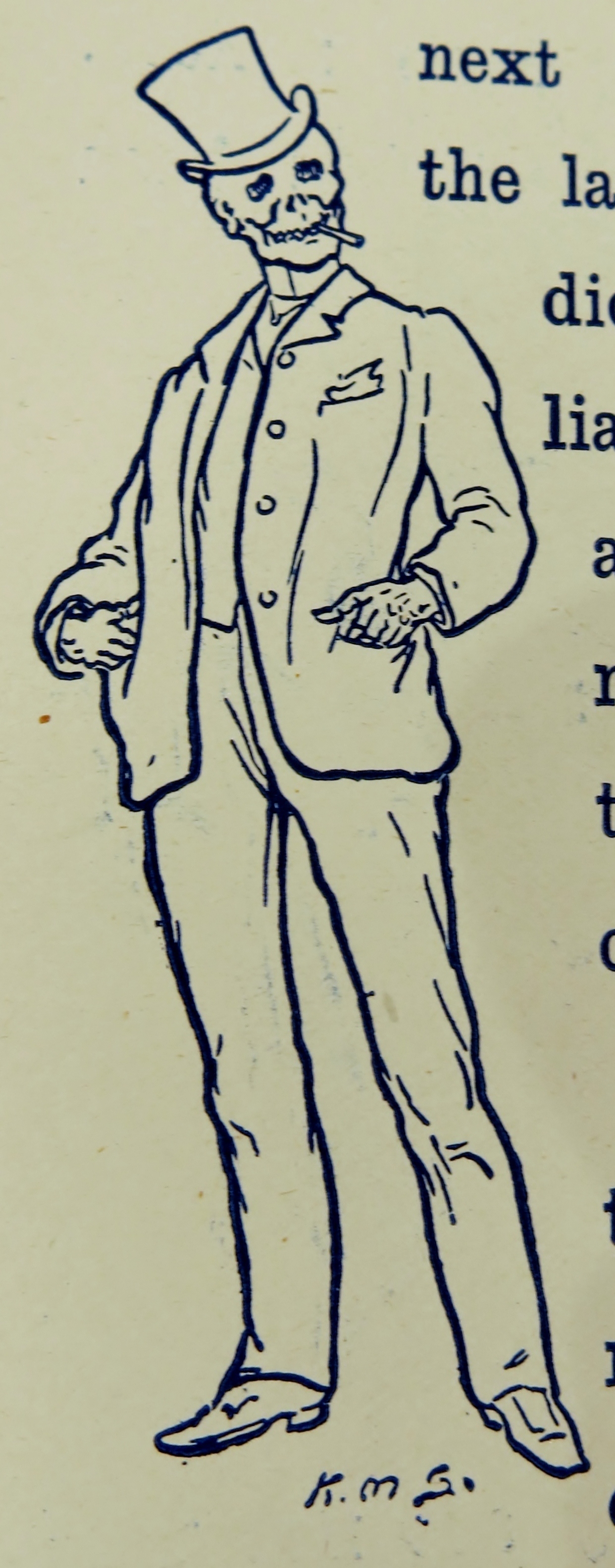

Today we commemorate the 85th anniversary of Black Tuesday, the worst day of the 1929 stock market crash that preceded the Great Depression. For a close-up look at these events, we turn to the papers of Henry P. Binney (1863-1940), a Boston banker and investment adviser. His voluminous outgoing correspondence, bound into 14 large letterbooks and covering the last thirty years of his life, forms part of the Henry P. Binney family papers.

The Wall Street crash began a few days before, 24 October 1929, on what came to be called Black Thursday. The bull market sustained through most of the 1920s had culminated in a record-high Dow Jones Industrial Average at the beginning of September 1929 before stock values started to tumble. Black Thursday saw the first precipitous drop. Nearly 13 million shares were traded in a single day, double the previous record and more than triple the volume of an average day. The boom was over. On that day, Binney wrote to a colleague who had proposed an investment opportunity:

On my return from a short trip to New York I find your letter of October 21st. While I do not know what reaction Mr. Ray Morris would now have regarding your proposition if presented to him I do not believe he or anybody else would consider anything new at this time. The tremendous shake-out of this morning in the stock market has taken the gimp out of pretty much everybody and it will take time for the panic of today to be forgotten. During the last week paper profits have faded away and many people rich at the beginning of said period are now poor.

To another investor on the same day, he wrote, “Everybody is pessimistic about everything just now.” Little did he know that Black Thursday would be followed by an even more frightening plunge in the market. On Black Tuesday, 29 October 1929, 16.4 million shares were traded in an all-out panic. While these numbers pale in comparison to the trading that we see on Wall Street today, they were unprecedented at the time. The stock ticker couldn’t keep up and ran hours behind as the market spiraled out of control.

One of Binney’s frequent correspondents during this period was his brother-in-law Roy E. Sturtevant. A week after the crash, he told Sturtevant:

Even the man who had his nose close to the grindstone on those fateful days did not, apparently, benefit much….Personally I don’t like the outlook. Such a tremendous crash as has occurred will take long to live down.

Binney’s prediction was prescient. He knew it would take years for the stock market to recover, but he did his best to stay optimistic and often reassured his friends and colleagues. On 30 January 1930, he joked to Sturtevant, who served as vice-president and treasurer of the Ludowici-Celadon Co. in Chicago:

I have just been reading your circular letter of January 28th to the stockholders, and have been looking over your figures for 1929. I imagine this is the first time the “Profit for the year” has been in red! However, lots of Industrials are on the same raft with you, so don’t be depressed.

Binney himself seems to have been less dramatically affected by the crash, at least initially, than many others. He was already a fairly conservative investor, preferring the safer bond market to risky stocks, and the events of October 1929 strengthened that tendency.

That’s not to say he didn’t feel the pinch. Between 1929 and 1932, the Dow Jones would lose about 90% of its value, bottoming out in July 1932. Curious to see how Binney was holding up, I looked ahead to his correspondence of that year. His letters had become more pessimistic and skeptical. I found him writing often about cutting back on utilities and luxuries, such as a proposed trip to Europe for his 18-year-old daughter Polly. He even swallowed his pride and accepted a gift from his brother- and sister-in-law, the Sturtevants:

Between ourselves, we will have to see how the depression works out. If matters remain as they are, it would be better in my judgment not to spend the money, especially as Europe is not a real necessity. I try not to be too gloomy when at home but, notwithstanding my efforts, both of my ladies have come to the conclusion that I had better hoard gold for contingencies. This being the case, I have decided to accept, with a million thanks, the check….No people I have ever known have ever been half as nice as you and Roy have been to us.

Unsurprisingly, his correspondence had also become more overtly political. He preferred Herbert Hoover to Franklin D. Roosevelt, but felt Hoover wasn’t up to the job. Binney feared a revolution if the Depression dragged on much longer. The relief measures he supported included a $5 billion bond issue to put people back to work, the repeal of Prohibition for additional revenue, and a tax on all manufactures. Here’s a sampling of his more political letters:

Needless to say I am dreadfully sorry to hear that you are so blue – it is quite the fashion here. However, things must turn or the U.S.A. will be faced by a Revolution before snow flies! I have no use for Mr. Hoover but even he may be better than whoever the Democrats nominate! Two or three days ago in New York I found rather a more cheerful tone although when one man laughed most of us fainted away at the unusual sound! [17 June 1932]

Lots of people think The Great Depression is on its last legs but, having turned pessimist, I am not at all certain of this. Apparently President Hoover will not be returned. I do not know a single Republican who will vote for him. The G.O.P. gentlemen all have their tails between their legs and either won’t vote at all or cast their votes for Roosevelt who nobody likes but, it is thought, cannot be as sloppy as H.H.! [13 July 1932]

The Depression seems to be passing, at least stock-marketwise. You had better print in your well[-]known newspaper that the one reason for this is the action of the Government in seriously attempting to put people to work. The method adapted is a little clumsy but what can one expect of Washington?! [9 Aug. 1932]

1. It is always Christmas Eve in a ghost story.

1. It is always Christmas Eve in a ghost story.