By Emilie Haertsch, Publications

This holiday, would you like to fancy up your cocktail by adding some founding father authenticity? Then the MHS has just the recipe for you in our collections. Ben Franklin sent James Bowdoin his recipe for “Milk Punch” on October 11, 1762. Here is the transcription of it as it appears in Franklin’s own hand:

Take 6 quarts of Brandy, and the Rinds

Take 6 quarts of Brandy, and the Rinds

of 44 Lemons pared very thin; Steep the

Rinds in the Brandy 24 hours; then strain

it off. Put to it 4 Quarts of Water,

4 large Nutmegs grated, 2 quarts of

Lemon Juice, 2 pound of double refined

Sugar. When the Sugar is dissolv’d,

boil 3 Quarts of Milk and put to the rest

hot as you take it off the Fire, and stir

it about. Let it stand two Hours; then

run it thro’ a Jelly-bag till it is clear;

then bottle it off. –

Now modern readers likely don’t cook on a fire or have jelly bags lying around, so the MHS provides an updated version of the recipe here. For the benefit of readers, I dutifully submitted myself to the task of testing it out to see how it would stand up to holiday festivities. My findings: if you want to get your party hopping fast, Franklin’s your man. His milk punch packs a wallop.

This is not a party drink you can decide to make at the last minute, however, because it requires more than 24 hours to prepare. The first step is to grate and juice your lemons. You will be up to your neck in lemons with this recipe (note that the original recipe calls for 44), so definitely give yourself plenty of time to grate and juice them. With the task completed, I placed the zest in a bowl with the brandy, covered it, and refrigerated it overnight. The lemon juice I set aside for the next day.

When I eagerly returned home the following day to inspect the brandy infusion, a heavenly citrus aroma wafted from the bowl. I removed the lemon zest from the brandy and added water, lemon juice, and sugar. Because I didn’t exactly have a whole nutmeg lying around (Stop & Shop was fresh out), I had to cheat a bit with that part of the recipe. I substituted the pre-grated spice instead, estimating the amount. I stirred the concoction until the sugar dissolved, but let’s face it – it was still mostly brandy. The temptation to try it then was strong, but I held out for the true Franklin experience.

When I eagerly returned home the following day to inspect the brandy infusion, a heavenly citrus aroma wafted from the bowl. I removed the lemon zest from the brandy and added water, lemon juice, and sugar. Because I didn’t exactly have a whole nutmeg lying around (Stop & Shop was fresh out), I had to cheat a bit with that part of the recipe. I substituted the pre-grated spice instead, estimating the amount. I stirred the concoction until the sugar dissolved, but let’s face it – it was still mostly brandy. The temptation to try it then was strong, but I held out for the true Franklin experience.

For the next step, I brought the milk to a boil on the stove and then added it to the lemon/brandy mixture. Lemon juice causes milk to curdle, which is intentional in this recipe. This was hard for me to wrap my mind around because usually if I curdle milk while working on a recipe I have done something very wrong. But as the curdled texture began to form in the punch I trusted in Franklin’s wisdom. This was all part of the process. To allow for a full curdling experience, I set the punch aside for two hours. Finally, I strained the curds out to leave a smooth liquid.

It was time to reap the fruits of my labor. I poured myself a glass and garnished it with a little nutmeg sprinkled on top. At last I experienced Franklin’s milk punch, and it was worth the effort. It is quite strong, although the tart, citrus taste hides that at first. The punch reminds me a bit of a whiskey sour, which I wouldn’t expect from a drink with the word “milk” in the title. But today I shared my experiment with other MHS staffers, and they weren’t all as enthusiastic. Some enjoyed it, but others found the flavor a bit medicinal. That’s not a bad thing for everyone – it could be a nice alternative to the hot toddy.

For myself, I would definitely make this recipe again for the right crowd. So if you decide you really want to make an impression at your bash this holiday, let ol’ Franklin help you out. You will be continuing a tradition that goes back at least 250 years. Now that’s worth a toast.

As the New Year approaches, many people set aside time to reflect upon their lives. What has transpired over the past 12 months? What were our successes? Where could we have improved? Charles Francis Adams, too, used the end of the year as an opportunity to evaluate his life, and the Society has his diary entries on the subject in the

As the New Year approaches, many people set aside time to reflect upon their lives. What has transpired over the past 12 months? What were our successes? Where could we have improved? Charles Francis Adams, too, used the end of the year as an opportunity to evaluate his life, and the Society has his diary entries on the subject in the

Take 6 quarts of Brandy, and the Rinds

Take 6 quarts of Brandy, and the Rinds When I eagerly returned home the following day to inspect the brandy infusion, a heavenly citrus aroma wafted from the bowl. I removed the lemon zest from the brandy and added water, lemon juice, and sugar. Because I didn’t exactly have a whole nutmeg lying around (Stop & Shop was fresh out), I had to cheat a bit with that part of the recipe. I substituted the pre-grated spice instead, estimating the amount. I stirred the concoction until the sugar dissolved, but let’s face it – it was still mostly brandy. The temptation to try it then was strong, but I held out for the true Franklin experience.

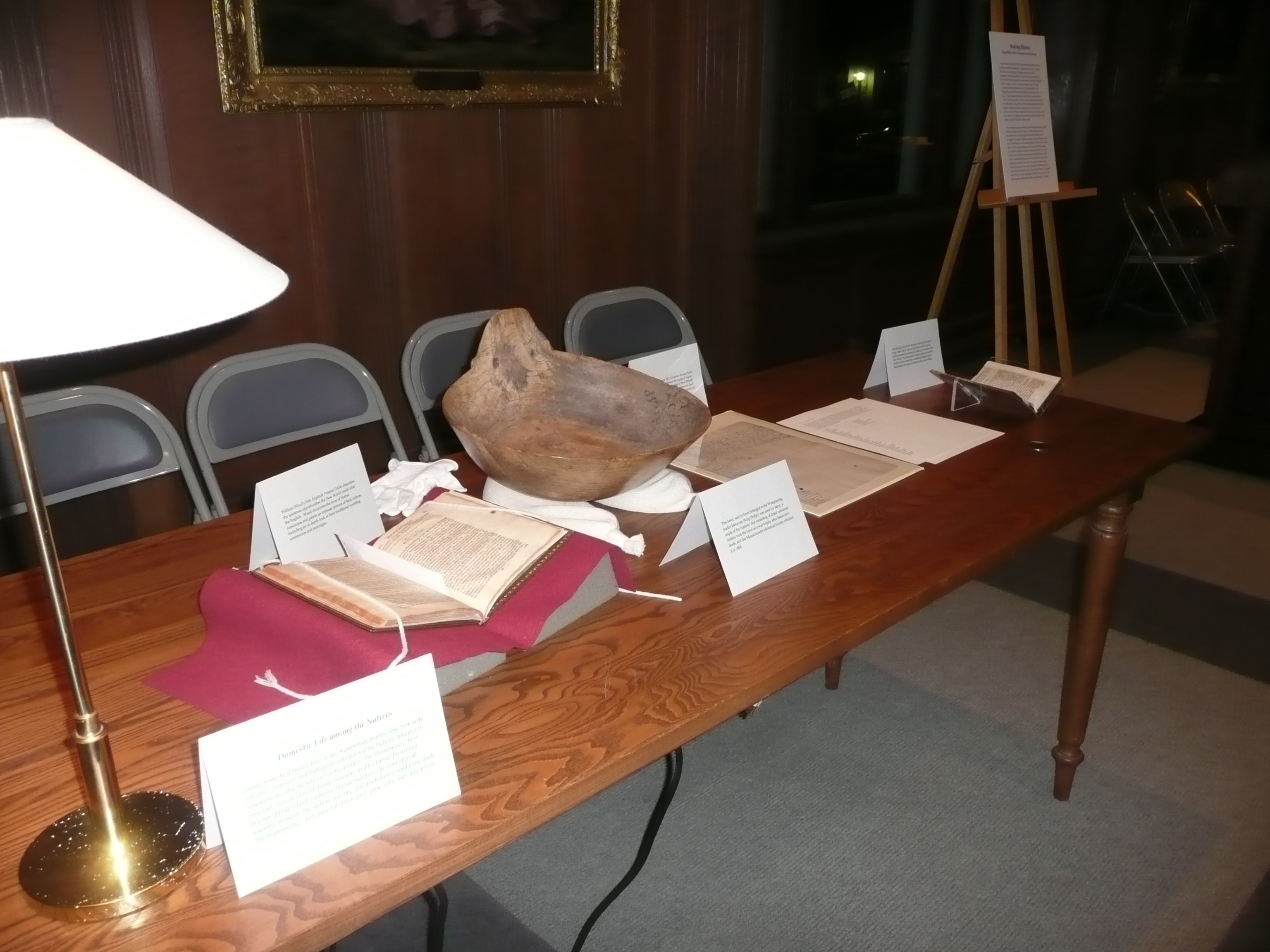

When I eagerly returned home the following day to inspect the brandy infusion, a heavenly citrus aroma wafted from the bowl. I removed the lemon zest from the brandy and added water, lemon juice, and sugar. Because I didn’t exactly have a whole nutmeg lying around (Stop & Shop was fresh out), I had to cheat a bit with that part of the recipe. I substituted the pre-grated spice instead, estimating the amount. I stirred the concoction until the sugar dissolved, but let’s face it – it was still mostly brandy. The temptation to try it then was strong, but I held out for the true Franklin experience. Students visited the MHS several times, both as a class and as individual researchers. They had the opportunity to analyze a series of manuscripts and published documents. Pamphlets such as John Eliot’s Strength Out of Weakness (1652), describe Puritan’s attempts to convert Indians to Christianity, while other works, like William Hubbard’s The Present State of New-England: Being a Narrative of theTroubles with the Indians in New-England (1677) suggest that not all native peoples were willing to adopt English customs or religious principles. Class members also transcribed a number of documents from the Winslow family papers, which include the papers of Edward and Josiah Winslow, colonial governors of Plymouth Colony from 1638-1680. Several letters in the collection detail colonists’attempts to negotiate with Metacom and other native inhabitants, even as native groups began forming alliances against the English settlers.

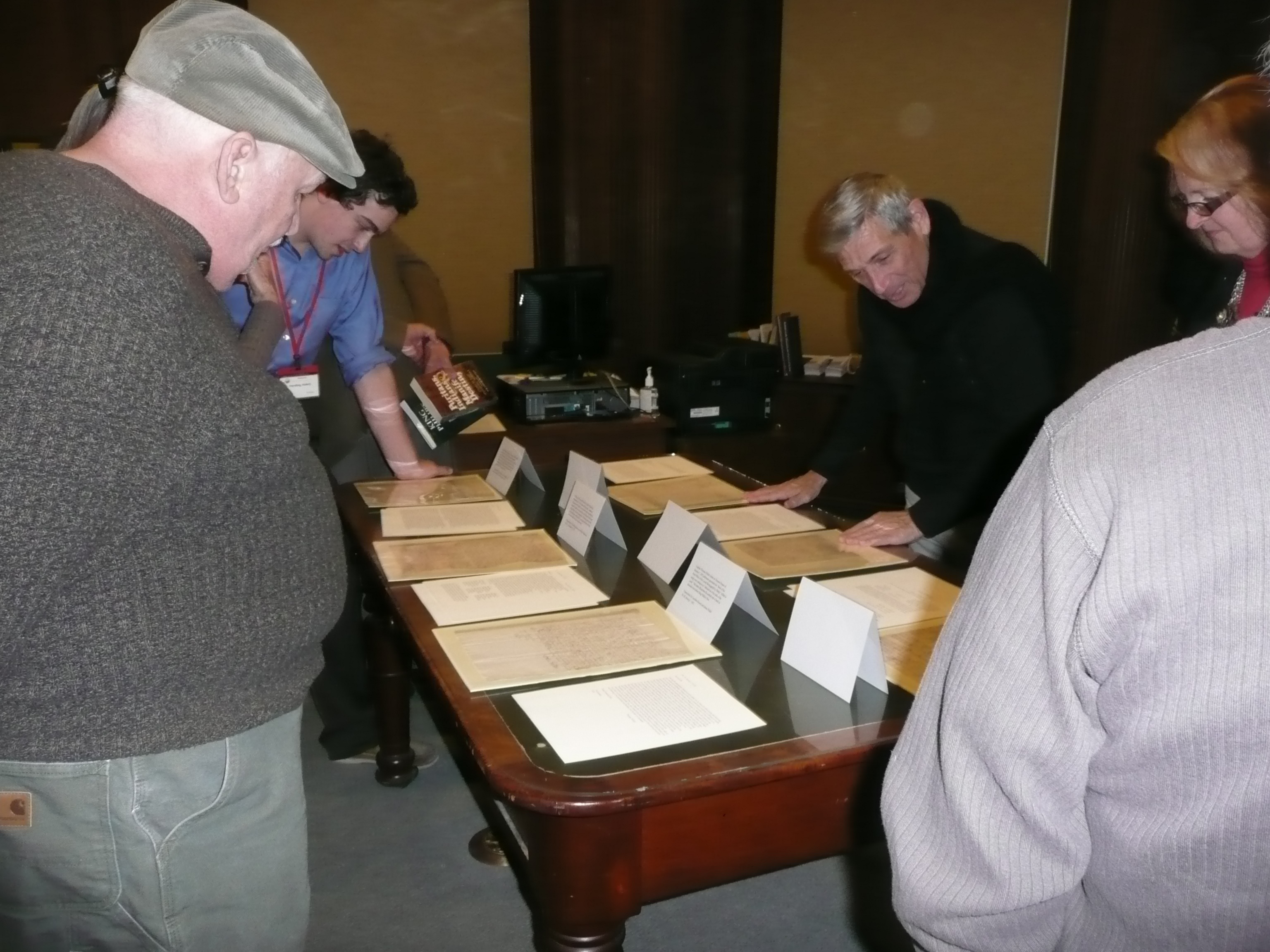

Students visited the MHS several times, both as a class and as individual researchers. They had the opportunity to analyze a series of manuscripts and published documents. Pamphlets such as John Eliot’s Strength Out of Weakness (1652), describe Puritan’s attempts to convert Indians to Christianity, while other works, like William Hubbard’s The Present State of New-England: Being a Narrative of theTroubles with the Indians in New-England (1677) suggest that not all native peoples were willing to adopt English customs or religious principles. Class members also transcribed a number of documents from the Winslow family papers, which include the papers of Edward and Josiah Winslow, colonial governors of Plymouth Colony from 1638-1680. Several letters in the collection detail colonists’attempts to negotiate with Metacom and other native inhabitants, even as native groups began forming alliances against the English settlers.

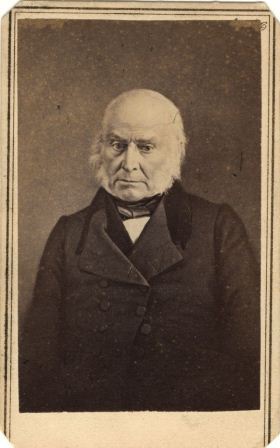

Recent viewers of Steven Spielberg’s film Lincoln may be wondering whether an Adams-Lincoln connection exists as the Adamses always seem connected to the major figures of American history. John Quincy Adams and Abraham Lincoln indeed served together in the 30th Congress for three months before John Quincy Adams died on February 23, 1848. Lincoln served on the Committee of Arrangements for Adams’s funeral, but that is the only conclusive connection between the two. They shared similar political outlooks, particularly on slavery, but what Adams thought about the young Lincoln, history does not record.

Recent viewers of Steven Spielberg’s film Lincoln may be wondering whether an Adams-Lincoln connection exists as the Adamses always seem connected to the major figures of American history. John Quincy Adams and Abraham Lincoln indeed served together in the 30th Congress for three months before John Quincy Adams died on February 23, 1848. Lincoln served on the Committee of Arrangements for Adams’s funeral, but that is the only conclusive connection between the two. They shared similar political outlooks, particularly on slavery, but what Adams thought about the young Lincoln, history does not record.