By Emilie Haertsch, Publications

It’s Election Day, and there has been a lot of talk in the news lately about terrorism influencing the current and last two presidential elections. But although sometimes it feels like it’s a relatively new political issue, the fear of terrorism has been part of the American political discussion since our nation’s founding. During the presidential election of 1800, terrorism and its prevention were hot topics, and part of what cost Pres. John Adams his reelection.

During Adams’s presidency, America was involved in the Quasi-War with France from 1798 through 1800. France was a great ally to the United States during the American Revolution, but much changed in the intervening years. The United States made peace with Great Britain in 1783, and several years later the French monarchy collapsed. Revolutionary France declared war on Great Britain, and Great Britain joined a coalition of European monarchies that aimed at containing the French Revolution. The United States remained neutral in the conflict. In addition, the U.S. government refused to repay debts owed to France from the American Revolution, claiming that they were owed to the French monarchy, which no longer existed. Ignoring American neutrality, French privateers began seizing American merchant ships in the West Indies. This led to an undeclared war between the United States and France—the Quasi-War.

Pres. Adams and the Federalist Party supporters aligned with Great Britain. They viewed the French Revolution as mob rule and resented what they saw as foreign intervention in American domestic politics. They also feared the threat of possible invasion. Adams signed the Alien and Sedition Acts into law in 1798. The four laws targeted French immigrants and sympathizers to the French cause, but also foreigners in general and anyone who criticized the government. The Alien and Sedition Acts increased the residency requirement for citizenship from five to fourteen years and empowered the president to deport aliens “dangerous to the peace and safety of the United States” at will. No one ever was prosecuted or deported as a “dangerous” alien and the law expired in 1800, but it had a chilling effect on resident aliens. A separate law that allowed the president to restrain or remove enemy aliens in wartime was the only act that had wide support in congress (and still is in effect today), but was not used by Adams because the U.S. never formally declared war on France. The laws also limited the freedom of the press, a sentiment that Adams had strongly supported as author of the Massachusetts Constitution. The Sedition Act gave the government broad power to suppress public attacks on the government and its officials, and, as a practical matter, allowed the Federalists to prosecute their political opponents. The Sedition Act also had a fixed term and ended on the last day of Adams’s presidential term in March 1801.

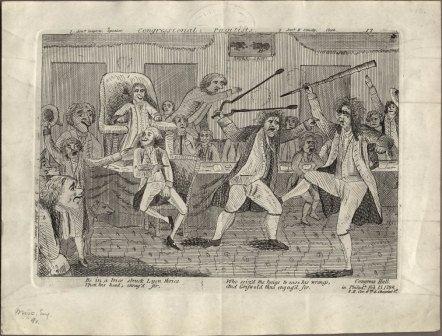

When the Federalists attempted to use the Alien and Sedition Acts to silence their opposition, they met strong opposition from the Democratic-Republican Party, a party more closely aligned with the ideals of the French Revolution and under the leadership of Vice President Thomas Jefferson. Most newspapers of the day were partisan, and when Republican newspapers harshly criticized the Adams administration for its handling of French relations, fourteen authors and editors were tried under the new Sedition Act. Playwright and newspaperman James Burke, Vermont congressman Matthew Lyon, and newspapermen Thomas and Abijah Adams were among those indicted for seditious libel.

The 1800 presidential election was a bitter continuation of the previous presidential election. One of the Democratic Republicans’ chief criticisms of the Federalist Party was of its efforts to centralize and increase governmental power, illustrated by the passage of the Alien and Section Acts and the resulting infringement on individual rights. Republicans were not necessarily against prosecutions for seditious libel, but believed they should take place in state rather than federal courts.

The Republicans won the election of 1800 and, at least in part because of the unpopular acts, Adams became a one-term president. He was succeeded by Jefferson who, in his conciliatory first inaugural speech, said that “…every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle. We have called by different names, brethren of the same principle. WE ARE ALL REPUBLICANS; WE ARE ALL FEDERALISTS.” His administration too soon would be at war with foreign “terrorists,” in this case the Barbary pirates, who attacked and kidnapped American sailors in the Mediterranean.

During the recent presidential debates, Pres. Barack Obama and former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney addressed their own positions on terrorism and homeland security. Although the threat may look slightly different now, with a greater focus on foreign terrorists rather than internal subversion, it’s nothing new to American politics. Just ask John Adams—and Thomas Jefferson. And don’t forget to vote!

and The Little Particle That Could. His books have been nominated for eight Harvey Awards honoring excellence in the comics industry and a Will Eisner Comic Industry Award. Rodriguez’s current project editing graphic novels about colonial New England brought him to the Massachusetts Historical Society last week. He took the time to answer a few Beehive questions about comics, history, and what to expect from the coming historical graphic novels.

and The Little Particle That Could. His books have been nominated for eight Harvey Awards honoring excellence in the comics industry and a Will Eisner Comic Industry Award. Rodriguez’s current project editing graphic novels about colonial New England brought him to the Massachusetts Historical Society last week. He took the time to answer a few Beehive questions about comics, history, and what to expect from the coming historical graphic novels.