By Emilie Haertsch, Publications

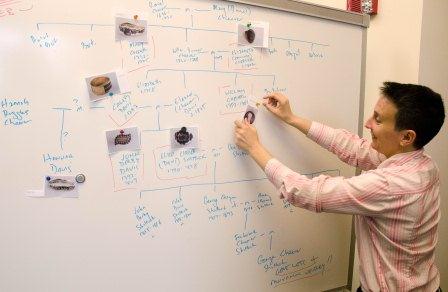

The protagonist of my favorite mystery novel series, Maisie Dobbs, creates a map of each case she works on. A London detective in the 1930s, she pins down a large piece of paper and writes down every bit of information she discovers, drawing lines to connect the pieces as the case evolves. Recently the staff of the Society’s Publications Department took a page out of Maisie Dobbs’s book and created a “map” to solve our own mystery regarding family connections and progeny.

We are working on a book to coincide with the Society’s upcoming exhibition on mourning jewelry. The book, titled In Death Lamented: The Tradition of Anglo-American Mourning Jewelry, features mourning jewels from the Society’s collection and from the private collection of the author, Sarah Nehama.

We are working on a book to coincide with the Society’s upcoming exhibition on mourning jewelry. The book, titled In Death Lamented: The Tradition of Anglo-American Mourning Jewelry, features mourning jewels from the Society’s collection and from the private collection of the author, Sarah Nehama.

Several mourning jewels used in the book were donated to the Society by Dr. George Cheever Shattuck in 1971, and although some of the people those jewels honored shared last names, we could not initially discern how they were all related. Many prominent families in 18th- and 19th- century Boston intermarried and used the same names throughout generations, making it difficult to differentiate mothers, sisters, and cousins. Many parents also named their children after close family friends, confounding things further for any genealogist.

With one woman in particular we struggled – Elizabeth Cheever. The inscription on her mourning ring had been transcribed as “Elizabeth Cheever obt. 28 June 1814 Aet 72,” indicating that she was 72 and died on June 28, 1814. Even with these details we could not find biographical information on her anywhere. That is, until we had the help of a great MHS volunteer. Kathleen Fox, who is assisting with this project, discovered that the date of death we had for Elizabeth Cheever had been transcribed incorrectly. Rather than 1814, it was 1802! With this new date we were able to find Elizabeth Cheever using the Town Vital Records Collections of Massachusetts on Ancestry.com. Formerly Elizabeth Edwards, she was born in 1730 and married William Downes Cheever.

From this new information we were able to link Elizabeth Cheever to Mary Cheever (her sister-in-law), William Cheever (her son), and so on. We created a family tree, researching each family member until we had connected seven generations of Cheevers, Davises, and Shattucks. The family tree includes those commemorated by all of the jewels Dr. George Cheever Shattuck contributed to the MHS. No mean feat. But we’re not done yet. We still need one confirmation on a Hannah Davis. The mapping – and mystery – continues. Sometimes working at a historical society is just like being a detective.

For more information on the Cheever, Davis, and Shattuck families, read this earlier post on the discovery of Elizabeth Cheever (Davis) Shattuck’s travel diary. She appears in the family tree, and In Death Lamented features a mourning ring commemorating her.

Just think of the variously colored steeples that dot the campus of Harvard in nearby Cambridge; the golden dome of the State House; and of course, the grand brownstones that line Newbury and Beacon Streets and Commonwealth Avenue. One architectural style that is not well represented in Boston, though, is the Tudor Revival style. And yet, just around the corner from the MHS, among the rows of stone and brick apartment buildings, is a fine example of that style.

Just think of the variously colored steeples that dot the campus of Harvard in nearby Cambridge; the golden dome of the State House; and of course, the grand brownstones that line Newbury and Beacon Streets and Commonwealth Avenue. One architectural style that is not well represented in Boston, though, is the Tudor Revival style. And yet, just around the corner from the MHS, among the rows of stone and brick apartment buildings, is a fine example of that style. A quick look at the building’s exterior shows one repeated feature that hints to its original use: around the building are several large portals — some arched — resembling modern-day garage doors giving the viewer the impression of stables.

A quick look at the building’s exterior shows one repeated feature that hints to its original use: around the building are several large portals — some arched — resembling modern-day garage doors giving the viewer the impression of stables.  Marian Hooper Adams was nicknamed “Clover” by her mother, who felt that her daughter’s birth was a lucky occurrence. Born into a wealthy, prominent Boston family, Clover was raised in privilege and highly educated. Her mother died when she was five, but Clover remained very close to her father for the rest of her life. In 1872, at the age of 28, she married the historian Henry Adams, who was teaching at Harvard. After five years they moved to Washington, DC, residing near the White House, and began hosting an exclusive salon of politicians, writers, and thinkers. Despite this stimulation, Clover and Henry were bored, and the spark went out of their marriage. Their problems intensified due to the fact that they were unable to have children.

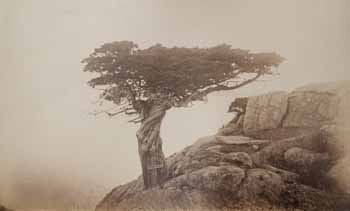

Marian Hooper Adams was nicknamed “Clover” by her mother, who felt that her daughter’s birth was a lucky occurrence. Born into a wealthy, prominent Boston family, Clover was raised in privilege and highly educated. Her mother died when she was five, but Clover remained very close to her father for the rest of her life. In 1872, at the age of 28, she married the historian Henry Adams, who was teaching at Harvard. After five years they moved to Washington, DC, residing near the White House, and began hosting an exclusive salon of politicians, writers, and thinkers. Despite this stimulation, Clover and Henry were bored, and the spark went out of their marriage. Their problems intensified due to the fact that they were unable to have children. Clover had always been interested in art and she found an outlet for her frustrations in a new camera in 1883. She learned the painstaking development process and began to take photographs of people, landscapes, and animals (she was a great lover of dogs and horses). Although a few of her photographs show traces of humor, including those of her dogs posed at a table set for tea, many of Clover’s photographs convey the melancholy and isolation of her own experience.

Clover had always been interested in art and she found an outlet for her frustrations in a new camera in 1883. She learned the painstaking development process and began to take photographs of people, landscapes, and animals (she was a great lover of dogs and horses). Although a few of her photographs show traces of humor, including those of her dogs posed at a table set for tea, many of Clover’s photographs convey the melancholy and isolation of her own experience.