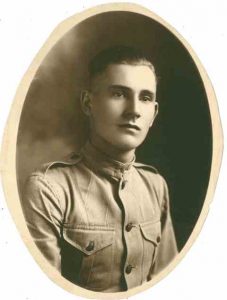

By Anna Clutterbuck-Cook, Reader Services

Today, we return to the diary of George Hyland. If this is your first time encountering our 2019 diary series, catch up by reading the January, February, March, April, May, June, July, August, and September 1919 installments first!

October begins “cloudy and cold” with temperatures in the 40s and occasional overnight frost. George is still busy helping bring in the autumn harvest — during October he picks tomatoes, cauliflowers, apples, pears, lettuce, potatoes, corn, and tobacco plants. He also travels to Boston to put more money down on his liberty bonds and to Hingham to assist with a large estate auction. Some of the small details are the most charming: He feeds the sparrows at Rowe’s Wharf in Boston; dances the Mazurka (a Polish folk dance) with friends; he walks to Egypt Beach and has to wait out a sudden rainstorm on the veranda of a house near the shore. He once notes that the stars are small and hazy, a “sign of storm.” There tiny glimpses, too, of the way George’s life is connected to a wider world beyond the South Shore. One of his tobacco plants is shipped to Seattle, Washington; on his trip to Boston he sees one of “the new U.S. destroyers … large ship – 4 funnels.” At the train station he runs into a veteran “recently returned from the war” in Europe.

Join me in following George day-by-day through October 1919.

* * *

PAGE 346 (cont’d)

Oct. 1. Worked 8 hours for E.F. Clapp – rode up with the horse and farm wagon. Had lunch at B. Brigg’s. Found me […]. Cloudy and cold in forenoon, W.N.W. aft. Clear, W.S.E. Eve. clear. tem. 40. Played on the guitar 1 hour in eve. Saw […] to-day.

2d. Worked 2 hours for E. Frank Clapp — on his farm in Norwell — Cloudy A.M., W.S. damp. Began to rain about 11:20 A.M. — light rain all

PAGE 347

day. Frost this A.M. Eve. clou. to misty. Played on the guitar 1h. 20m. in eve. I have a cold. With cough. 12 (mid.) thunder tempest W. of here.

3d. Fine weather, W.S.E. tem. 76. In aft. mowed, trimmed and raked lawn 1 1/4 hours for Russell Wilder — 50. Late in aft. picked up some boxes and other things for fuel — cut it up and housed it. Eve. cloudy — W.S.E. Played on the guitar 1h. 20m. in eve. I have a bad cold.

4th. Cloudy to par. clou. tem. 74. Played on the guitar 1 hour in eve. (Rain in eve.)

5th. (Sun.) Foggy and misty rain at times day and eve. Mr. James called here in forenoon — had job for me. Mr. S.T. Speare also called to see if I will mow his grass.

6th. Cloudy. Foggy A.M. warm N.S.W. rain all day — tem. 72. Went to the R.R. Station (opp. This house) early in eve. 5:40 P.M. Paul Briggs there — also [space left blank for name] of Norwell — recently returned from the war — is a French […] — was in 39th U.S. Inf. 4th Div. 2d […] in U.S. Army. They were waiting for the 6:19 P.M. tr. Eve. clear. Fine. Played on the guitar 1 h. 10 min. In eve.

7th. Worked 8 hours for E. Frank Clapp — on his farm in Norwell — [space left blank for amount owed]. Picked 10 bus. of ripe tomatoes, and helped E. F. C. harvest and pack 40 bus. of cauliflowers — Mrs. [space left blank for name] there — she cut and packed them. I brought them home with the horse, and they brought the tomatoes home in the auto. I got some bread at Fred Litchfield’s, and some milk at Mrs. Merritt’s. Fine weather. Clear nearly all day — W.W. in afternoon — N.W. late in aft. Windy. Air dry. Fine eve. Played on the guitar 1 h 10 min. in eve.

8th. Worked 8 hours for E.F. Clapp. [space left blank for amount owed]. Picking ripe and green tomatoes and helped E.F.C. and [space left blank for name] get a load of cauliflowers — 40 bus. They carried home the cauliflowers in the auto and I carried home the tomatoes with the horse and wagon. Ate my dinner at B. Briggs. Olive made some tea for me. A large automobile with members of the Bap. Church passed me in morning — when I was walking up to E.F. Clapp’s, and Fred T. Bailey drove the leading one — a large car (limousine) stopped and invited me to ride with them.

Cold A.M. W.N.N.W. wind S.E. after 5 P.M. S. later in eve bought some bread at F. Litchfield’s and some milk at Mrs. Merritt’s. Played on the guitar 1 h. 25 m. in eve.

9th. Worked 8 hours for E. Frank Clapp — picking tomatoes (ripe) — are worth $5.00 per bu. To-day went to the farm in Norwell with the horse and wagon. Frost this A.M. Very chilly wind — S.W. par. Clou. in aft. Began to rain when I arr. at E.F. Clapp’s (7 P.M.) and rained all eve. Warmer. Played the guitar 1 h. 10 min in eve. Carried my dinner — ate at B. Brigg’s. Bought bread at F. Litchfield’s and milk at Mrs. Merritt’s. Light rain all night.

10th. Light rain early A.M. Forenoon clou. to par. Clou. Very warm in aft. — tem. To-day 66-80; W.W.S.W. Picked tomatoes for E.F. Clapp — in aft. — went to the farm late in forenoon with the horse and wagon — brought home 18 bus. Of tomatoes. Eve. par. Clou. W.N.W. bought some milk at Mrs. Merritt’s. Played on the guitar 1 h. 15 m. in eve. Worked 6 hours to-day for E.F. Clapp.

11th. Worked 6 hours for E.F. Clapp — picking tomatoes on the farm in Norwell. Brought them home with the horse and wagon. Hot weather — tem. 72-83; W.W.; clear to par. clou. Carried a light dinner. At it at B. Brigg’s — also had some of their dinner. Began to sprinkle — light rain about 3:30 P.M. W.N.W. E.F. Clapp and Mrs. [space left blank for name] came here in eve. And paid me for all work to date — 10 days, 5 hours — 25.50. Played on the guitar 1 1/4 hours in eve. Rain late in eve. W.N.W.

12th. (Sun.) Clou. light rain at times in aft. W.M.E. Very cool. 11:30 A.M. clear. W.N.W.

PAGE 348

13th. Worked 4 hours for Mr. James — clearing out buildings and doing carpentry work. Fine weather, tem. About 35-65; W.N.W. and S.E. Cut down some of my tobacco plants — brought it home and drying it out in the woodhouse. Also picked some of the seeds. I have 50 large plants — raised them on the James place. Played on the guitar 1 1/4 hours in eve.

14th. Went to Boston — on 9:15 A.M. tr. Paid the last instalment on the 5th Liberty Bond. (Victory Liberty Loan) Forenoon cloudy; W.W. rain all aft. W.S.E. bought some groceries at Cobb Bates store. Returned on Steamer “Betty Alden” to Pemberton, tr. to Nantasket Junction, then tr. to N. Scituate. Arr. 4 4 P.M. Light rain in eve. Saw the new U.S. Destroyers — “129” passed by her. Is large ship – 4 funnels. I gave the sparrows at Rowe’s Wharf some [bread] I give them some every time I go there. Played on the guitar 1 1/4 hours in eve.

15th. In forenoon did some work at home — washing and etc. In aft. Worked 3 hours for Mason Litchfield — mowing lawn and trimming grass around the house — 65. Cloudy. Very damp. Warm. W.S.W. tem. 72. Played on the guitar 1 1/2 hours in eve.

16th. In forenoon worked 2 ½ hours for Mr. James — carpentering. In aft. worked 3 hours for J.H. Vinal — in the store and loading and unloading goods — 90. Late in aft. cut down all my tobacco plants (50 large plants) and brought them home and put them in the woodhouse — tied them up in bundles. Got some lettuice [sic] in my garden — gave some to Mrs. Mary [blank space left for name] J.H. Vinal and Mrs. Bertha Bates (nee Holson). Very warm weather, W.S.W. tem. 76 cloudy, light rain at times in aft. Eve. cloudy, warm. Played on the guitar 1 1/2 hours in eve. Heavy thunder tempest at 10 P.M. W. of here. Rain here, 10:45 tempest passed close by here — thunder at same time. 11 P.M. raining. Tempest about done. Gave Mrs. [space left for name] E. James Jr. one of my tobacco plants to send to Seattle, Wash. 11:15 P.M. tempest has passed to the S. of here — steady rain here.

17th. In aft. picked apples 3 hours for Mrs. Eudora Bailey — picked […] on a very large R.I. […] tree (3 barrels) Light rain in morning. W.N.W. aft. and eve. clear. Played the guitar 1 1/2 hours in eve.

18th. Worked 7 hours for Mrs. Eudora Bailey — mowing and trimming the grass on W.S. and N. sides of the house — also the bank, and picking pears. Put 3 barrels of apples and 2 bus. of pears into the cellar, and housed 1 cord of wood. 10 hours in all — 1.50. Mrs. B. gave me some of the pears (Burr, Bosc) and apples, also a piece of brown bread. Mr. James paid me 1.00 for work I have done for him (I did not charge much for what I did.) Very fine weather, W.N.W. in forenoon — S.E. in aft. Fine eve. Played on the guitar 1 1/2 hours in eve.

19th. (Sun.) Fine weather. In aft. (2:45 P.M.) went to Egypt Beach and N. Scituate Beach via Hatherly Road — ret. via Surfside road — got some sea moss. Walked all the way. arr. Home at 6 P.M. eve. Very cool. W.N. hazy.

20th. Dug potatoes 6 hours for Mrs. Bertie Barnes (nee Clapp) — 1.50. Had dinner there. Very cool; par. clou. to clear — W.N.E. Eve. cold. Played on the guitar 1 1/4 hours in eve.

21st. Dug potatoes 6 1/2 hours for Mrs. Bertie Barnes — 1.50. Had dinner there. Par. clou. to clou. W.S.W. and S.E. arr. home at 2 P.M. began to rain about 7:15 P.M. Bought some milk at Mrs. Barnes’ — she gave me 2 qts. of buttermilk to take home. Played on the guitar 1 hour. 10 min. In eve. Rain all eve — light rain. Frost this A.M.

22d. Dug potatoes 6 hours for Mrs. Bertie Barnes — 1.50. Had dinner there. Fine weather — W.W. clear after 10:30 A.M. Eve. clear. Played on the guitar 1 1/4 hours in eve.

23d. Worked 6 hours for Mrs. Bertie Barnes (fin. diging [sic] the potatoes in forenoon and harvested the corn and stalks and house them in aft. — 1.50. I had dinner there. Her daughter Mrs. Dorothy Wilder there to-day.

PAGE 349

Her two little granddaughters — Priscilla and [blank space left for name] with me most all the time — helping me. Mr. Israel is a cripple, and Mrs B. runs the farm. She sent me a pint of buttermilk in eve. Clou. to par clou. To-day; W.S. to S.E. damp eve. Cloudy. Raked and cocked up some hay for Mrs. M.G. Seaverns after dark — (15 min.) Played on the guitar 1 hour, 25 m. in eve. Met Mrs. Eva [blank space left for name] in Mrs. Seaverns’ store early in eve. She introduced me to her step-daughter, and invited me to call at their place at No. Scituate Beach.

24th. Cloudy; W.N.E.; tem. 50-55. In aft. went to Hingham — to Henrietta’s. Had dinner there — spent aft. There. Ret. on 5 P.M. tr. Saw Lottie (Mrs. Whiton) just as I was about to get aboard a car — she came from Boston on same tr. I came home on — she lives in Groton, opp. N London, Conn. and came on a visit to her mother’s (Henrietta.) Eve. cloudy, W.N.E. 10 P.M. Stars look very small — hazy — sign of storm. Played on the guitar 1 1/2 hours in eve.

25th. Went to Hingham Cen. Great auction at Henrietta’s — furniture, pictures, and many kinds of goods sold. I worked there at geting [sic] the things out of building and assisting in the auction. Ethel and I assorted [sic] the things, and I helped Arthur Whiting to move them. Had dinner and supper there. Lottie got the dinner and supper. Road about 1/2 way to Cohasset Sta. with James H. Merritt in auto-truck — had a load of vegetables, fruit, and etc. Then I walked nearly to N. Cohasset Sta. (3 miles) — then rode to Henrietta’s with Mrs. [blank space left for name] Hall in her auto. Mrs. Binney, her mother, and Mrs. [blank space left for name] Merritt with her. She invited me to ride back home with them but I went back on tr. from Hingham Sta. 7 P.M. tr. arr. N.S. 7:15 P.M. Par. clou. W.N.E. and S.E. good weather. Eve. clou. Played on the guitar 1 hour in eve.

26th. (Sun.) Warm weather, W.S.W. tem. 76. Late in aft. went to Egypt Beach — via Mann Hill. aft. clou. just as I arr. there it began to rain. Staid [sic] on the veranda of a house near the beach. At 3:45 P.M. started for home — arr. 4:30 P.M. walked 3 m. in 45 min. Eve. cloudy. Warm. Light rain at times.

27th. Went to Hungham (9:12 A.M. tr.) Walked to Hingham Cen. and helped at the Auction — assistant to the auctioneer (Chauncy O. Davis, Hanover Cen., Mass. Tel — Hanover — 79-5). Ethel and I selected the things and I carried them to the auctioneer’s stand (near there) and Arthur Whiting placed them where people could see them. Auction began at 12:33 P.M. and finished at 6 P.M. Everything in all the buildings were sold. Arthur Whiting lives in West Hanover, Mass. Ethel H. Studley administrator of the estate. Had dinner and supper at Henrietta’s and staid all night. Arthur W. and I carried some furniture back into the large barn — for Mr. O. Smith, and he gave us each 50cts. Clou. A.M. fine weather after 11 A.M. Ethel played on her new piano in eve. Clou. W.E. in eve. Rain late in night.

28th. Staid at Henrietta’s. Helped Mr. Smith get his furniture out of the building (about 1 hour). He paid me 50cts. Did some chores on the place. Lottie went home this forenoon. Frank went to Scituate in eve. in his auto: to bring his mother home. Ellen came to Hingham with them — for a visit. I staid all night. Ethel played on the piano over an hour in eve. Very warm weather — W.S.W. […] temp. 82. About 5:30 P.M. par. Clou. — wind changed to N.W. very windy. Very cool in a few […] cold and windy all night. Henrietta and I danced the Mazurka — Ethel played it on piano.

PAGE 350

29th. Staid at Henrietta’s until 1 P.M. Did some chores. Had dinner there. Mrs. Keenan worked there to-day. Ethel gave me $5.00 for assisting at the auction — and Mr. Smith gave me 1.00 for work I did for him. Made $6.00 in all. Henrietta gave me some pieces of cooked meat to bring home. Came back on the 1:50 P.M. tr. Saw Ellery F. Hyland near Hingham Sta. One of the tires on his auto-truck was punctured — I loaned him $8.50 to get it repaired. Late in aft. Chopped old board and planks 1 1/2 hours for Mrs. M.G. Seaverns — 30. Very cool day and eve. Played on the guitar 1 1/4 hours in eve.

30th. In forenoon swept and cleaned the Bates & Wilder Store for J.H. Vinal — has been using it to store goods in — is done with it now — lease expired. He gave me all the wood and boxes, a table, 2 flour bags (cloth) and a broom for cleaning the store — and brought them here in his grocery wagon. In aft. Worked 1 2/3 hours for Herbert Bates 45.– transplanting grape vines (4) also transplanted a rambler rose bush for Mrs. Mary Wilder (his sister) they live in a house close to the river — I got the water (to water the vines) from the river — then I transplanted 3 grape vines for Russell Wilder — 1 hour — 30. Then I picked up a small load of kindling wood — where the laundry building (close to my house) was torn down and J.H. Vinal and I carried it to his place and put it in his cellar. 1 hour — 25. Was dark then — then I got some of the wood for my use and put it in the house. Played on the guitar 1 1/2 hours in eve. Cloudy; W.E. to S.E. damp. Eve. clou.

31st. Picked wood out of the pile of rubbish where the old Chinese laundry was torn down. Also got some junk. Rain nearly all forenoon. W.S.W. clou. aft. and eve. W.E. Played on the guitar 1 1/2 hours in eve. Have worked 7 hours in all where the laundry building stood.

* * *

If you are interested in viewing the diary in person in our library or have other questions about the collection, please visit the library or contact a member of the library staff for further assistance.

*Please note that the diary transcription is a rough-and-ready version, not an authoritative transcript. Researchers wishing to use the diary in the course of their own work should verify the version found here with the manuscript original. The catalog record for the George Hyland’s diary may be found here. Hyland’s diary came to us as part of a collection of records related to Hingham, Massachusetts, the catalog record for this larger collection may be found here.