by Aaron Peterka, MHS Early Career Scholar Committee & Mentorship Program Member

Over the course of 250 years, the grass-covered mounds of Cambridge’s Fort Washington morphed from a necessary military fortification to a lasting monument to the American Revolution’s early perils. It is also a monument to another kind of metamorphosis: that of a colonial citizen army outside Boston in 1775-76 to the professional Continental Army that emerged victorious at Yorktown in 1781. Diaries from the MHS archives, like that of Boston merchant William Cheever, clearly illustrate the hazards for the New Englanders who faced the British, who, though besieged, were still mobile and active in late 1775/early 1776.

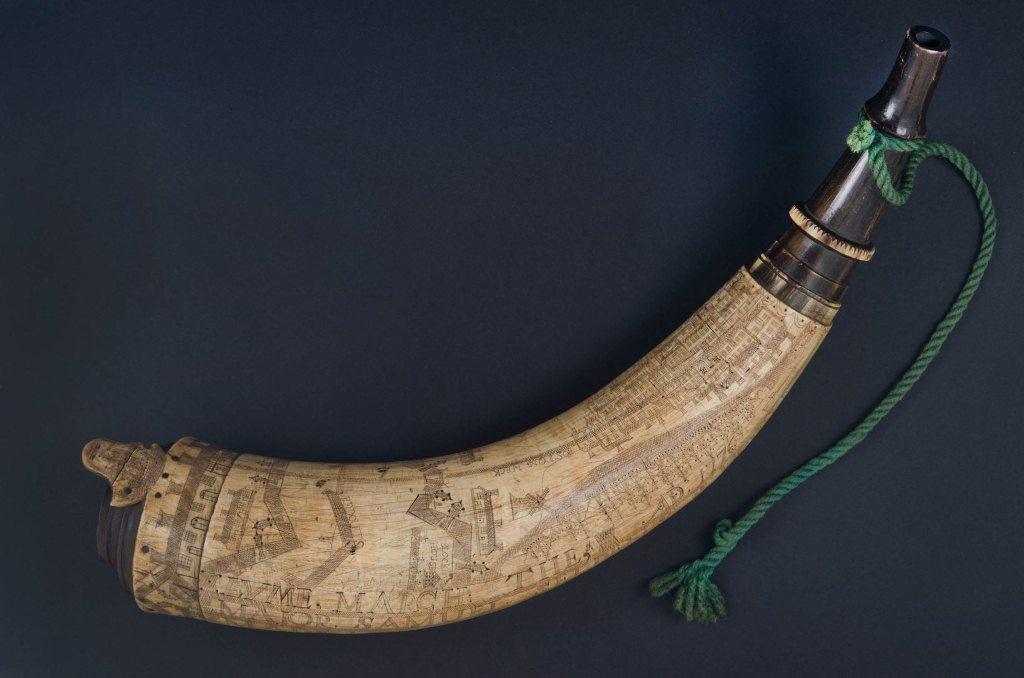

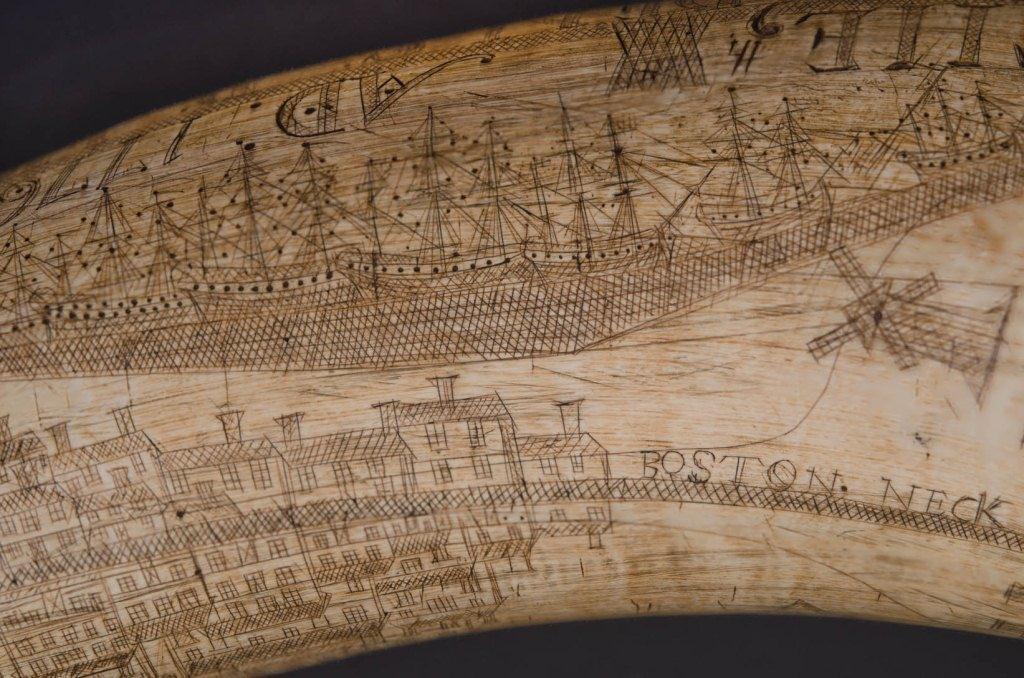

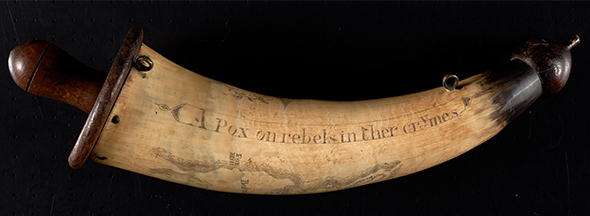

In one entry dated November 9, 1775, mere weeks before Fort Washington’s construction began, Cheever noted that “Several Companies” of British regulars crossed over to “Phip’s Farm” and “brought off some Cattle at noon day under Cover of a Ship in the River, Cannon on Charlestown point, and their own Floats.” He recorded a similar raid that took place on February 14, 1776, wherein the night before, “a Number of the Light Infantry and Grenadiers went over to Dorchester Neck and burnt 4 or 5 Houses” and took several prisoners. Moreover, as the Americans continued to entrench in front of Cambridge, the British did likewise in Boston. Cheever noted on December 4, 1775, that the “regulars have a Battery just above the Copper-Works” in west Boston, as well as colonial artillery dueling British ships “at the head of the Charles River,” as the British attempted to keep the Americans from “carrying on their Works on a Rise at Phips’s Farm.” Soldiers like Private Obadiah Brown of Gageborough, Massachusetts, could easily supplement Cheever’s observations, as Brown recalled an ordeal on February 20, 1776, where the British “Regulars fired all Day” at him and his comrades as they dug trenches at “Leachmore point.”

Such accounts bring to life the hardships and precarity of the Revolution’s earliest days, and it is to this narrative of trial and peril, so carefully preserved in the MHS’s collections, that Fort Washington belongs. However, that narrative not only includes the challenges of containing a worthy foe, but also the complex characters of those soldiers who held the line in bastions like Fort Washington.

Courtesy of Aaron Peterka.

In the summer and fall of 1775, General Washington hardly held those soldiers in high esteem. He lamented their apparent self-centeredness, poor discipline, and civilian attitude, writing to Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Reed on November 28, 1775, that “such a dirty mercenary Spirit pervades the whole, that I should not be at all surprised at any disaster that may happen.” Granting generous furloughs just to keep up enlistments, the general also despaired over the Connecticut regiments’ refusal to extend their service beyond their original term, fearing that absent soldiers and expiring enlistments would weaken his army to the point of disintegration. “[O]ur lines will be so weakened that the Minute Men & Militia must be call’d in for their defence,” Washington ruefully observed, and “these being under no kind of Government themselves, will destroy the little subordination I have been laboring to establish.”

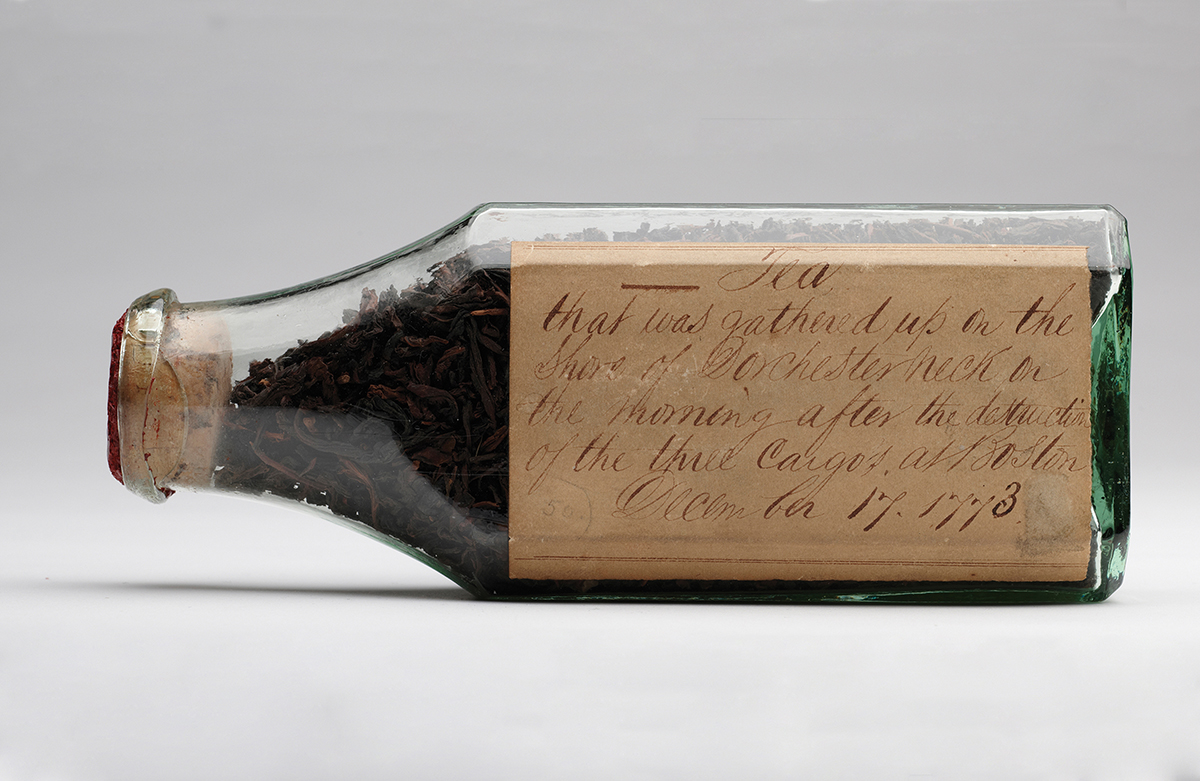

The diary of the aforementioned Private Brown allows for a glimpse into Washington’s conundrum. Oftentimes, Brown stood “gard” or performed “feteague” duty at the “Leachmore point” fort from January to March 1776. But interspersed throughout his terse entries are observations of drunkenness and ill-discipline; the kind that would drive mad a professional soldier like Washington. In one instance on February 7, 1776, “Two Sodiers Drank 33 glases of Brandy and Gin one Died.” Five days later, Brown witnessed another soldier receiving “39 lashes” for an unspecified indiscretion. And on February 16, 1776, Brown recalled that “orders came for one Shilling to be taken out of the Sodier wages for Every Cartridg Lost,” a stark reflection of the dire shortage of shot and powder that threatened the army, as well as the general unmilitary air that characterized the army in New England. And despite its successful re-occupation of Boston in March 1776, this same army would endure defeat after defeat in the coming years, and through the miseries of Valley Forge, painfully transform into the Continental Army that would ultimately prevail at Yorktown. Fort Washington is a testament to the beginning of that metamorphosis.

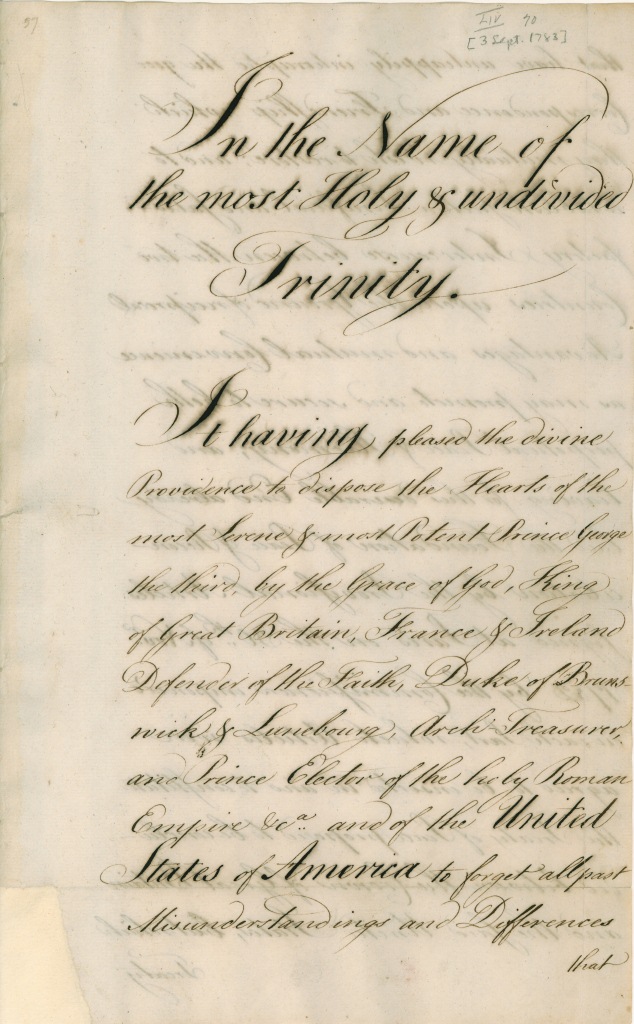

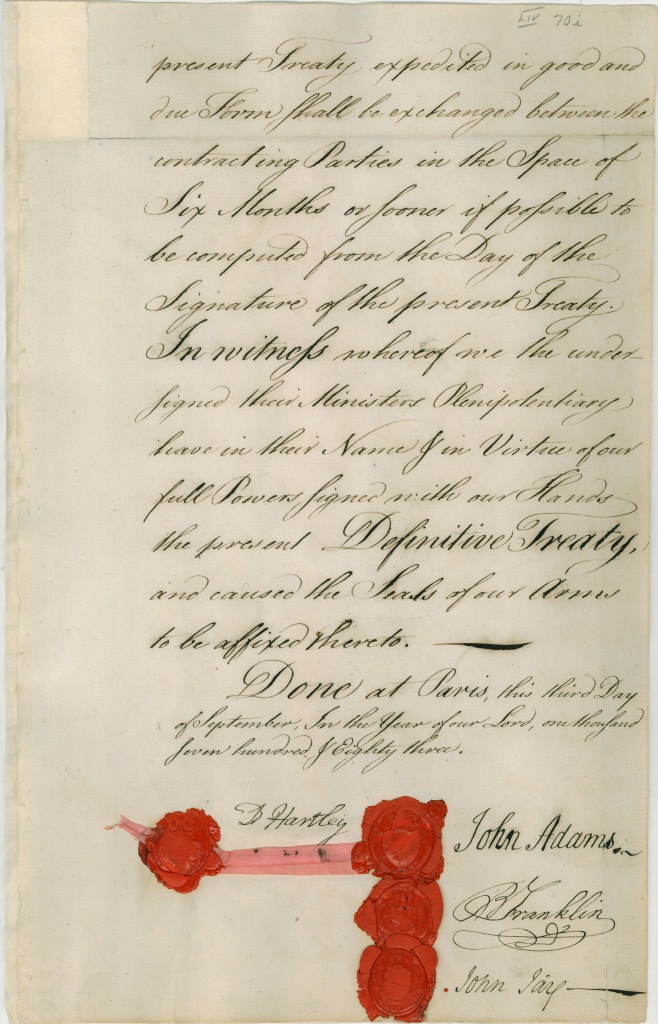

It is this complicated history of which Fort Washington is a part. It is a reminder of the challenges and contradictions that shaped the Revolution and this country’s birth: the fierce independent spirit that drove the colonists to rebel and made them poorly disciplined soldiers; the uncertainties of maintaining adequate supplies and manpower; and the looming threat posed by the growing might of the British army in Boston. In a time when the United States remains the world’s superpower, its military might thus far unmatched in the 21st century, it is easy to forget these truths. And yet, Fort Washington continues its silent vigil; a memorial that compels all who reflect upon it to remember “the times that try men’s souls.”

Further Reading:

“From George Washington to Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Reed. 28 November 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0406.

Thomas Paine. Common Sense and Other Works. New York: Fall River Press, 2021.