By Susan Martin, Collection Services

I recently processed a manuscript collection that contains some terrific material related to the Boston Lyceum for the Education of Young Ladies, a school founded by Dr. John Park (1775-1852) in 1811. I’d never heard of the school before, but in a matter of weeks, very similar papers cropped up in two other collections here at the MHS, like an archival version of the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon.

John Park had been a physician in the West Indies from 1795 to 1801, then a newspaperman in Newburyport and Boston, Mass., before founding his Lyceum. The school gave girls a classical academic education rather than lessons in the usual “feminine accomplishments.” Classes were held at Park’s home in Beacon Hill, and he did all the teaching himself. He was, by all accounts, a gifted and enthusiastic teacher, respected and loved by his students.

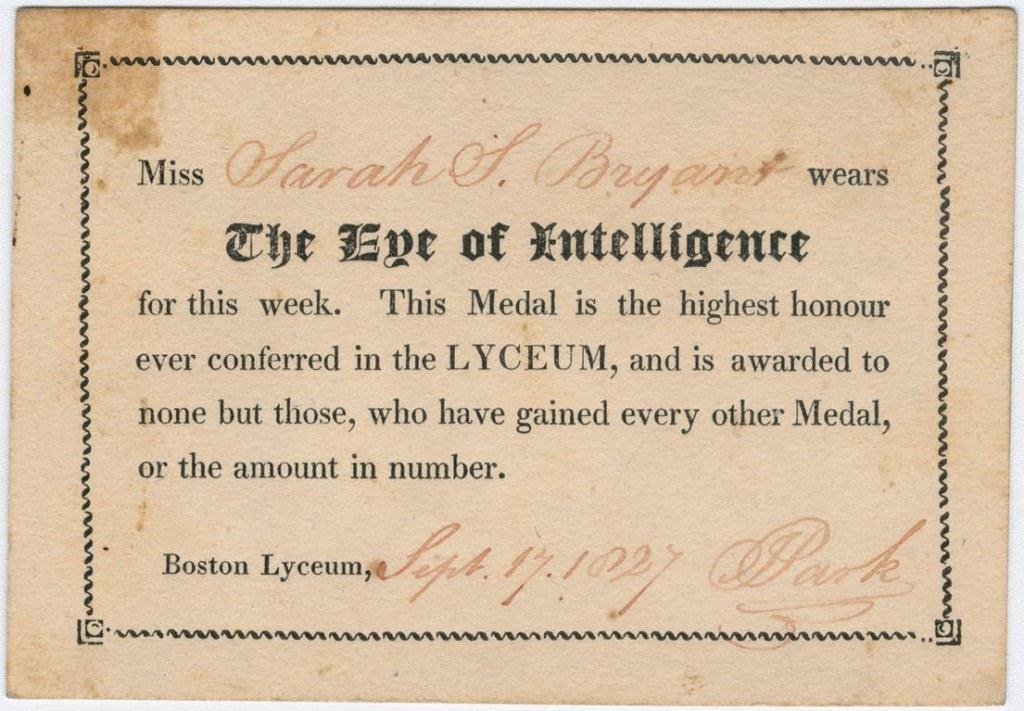

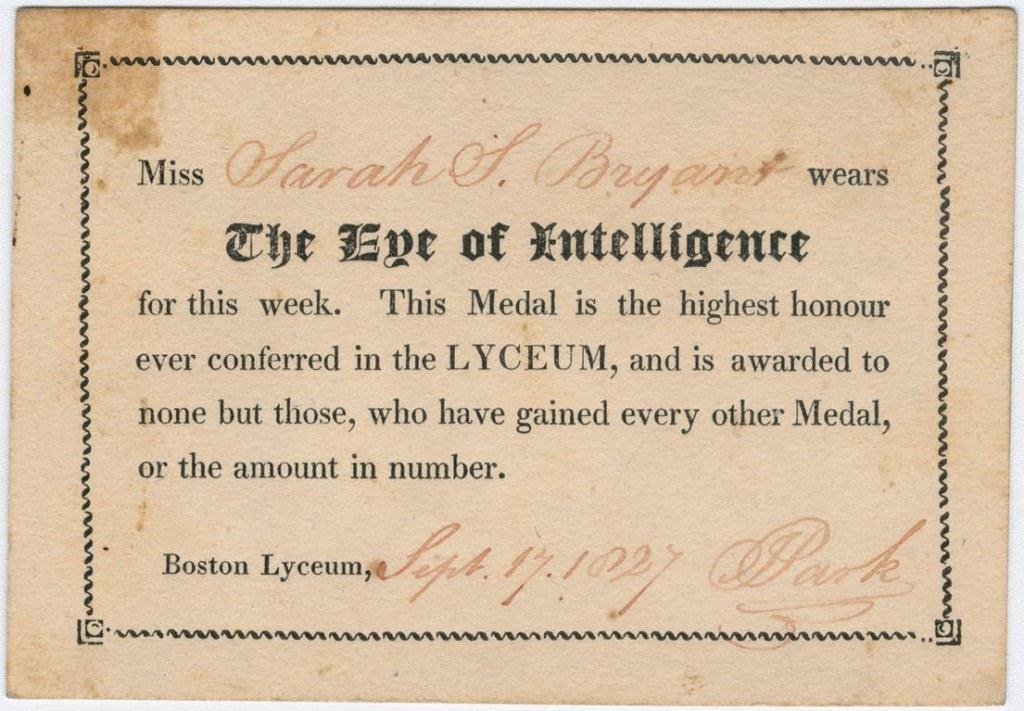

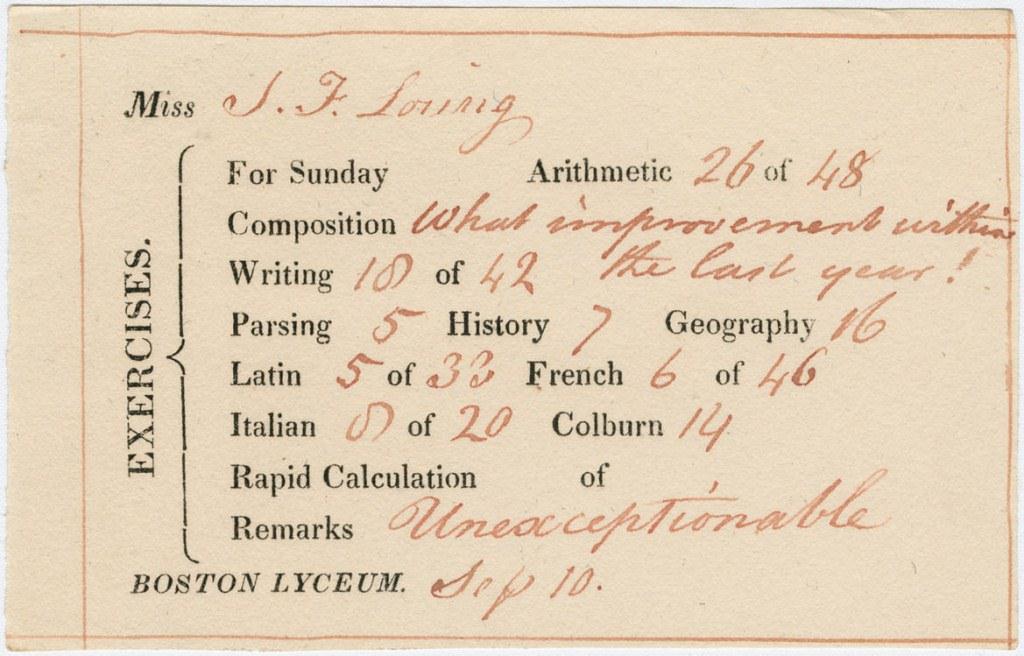

Sarah Bryant (1812-1887) was one of the many daughters of prominent Boston families who attended the school. The Fay-Mixter collection contains several small (approximately 3 ¾ x 2 ½ inches) “report cards” filled out by Dr. Park, 1827-1829, recording her marks in arithmetic, composition, parsing, history, geography, Latin, French, Italian, and other subjects. Park felt ranking his students and rewarding high achievers with “medals” promoted healthy competition. Sarah Bryant earned medals for good composition and good improvement, as well as a whopping seven Eye of Intelligence awards, “the highest honour ever conferred in the Lyceum.”

Dr. Park also wrote personal remarks on most of the cards. He described Sarah as “one of the best writers in the Lyceum,” “correct and bright,” with “powerful natural talents” that were being “successfully cultivated.” Park was “highly gratified” with her academic work, but unfortunately she had one bad habit that frustrated him: leaving her seat to socialize with other students. He wrote: “Miss Bryant has quick powers and holds a high rank.[…]I have only to regret her being so frequently out of her seat, conversing with those who do not sufficiently value their time.” On another card, he described her as “very capable, but too much like Hamlet’s ghost ‘hic et ubique.’” (Translation: here and everywhere.) His advice? “Steady habits would perfect the scholar.”

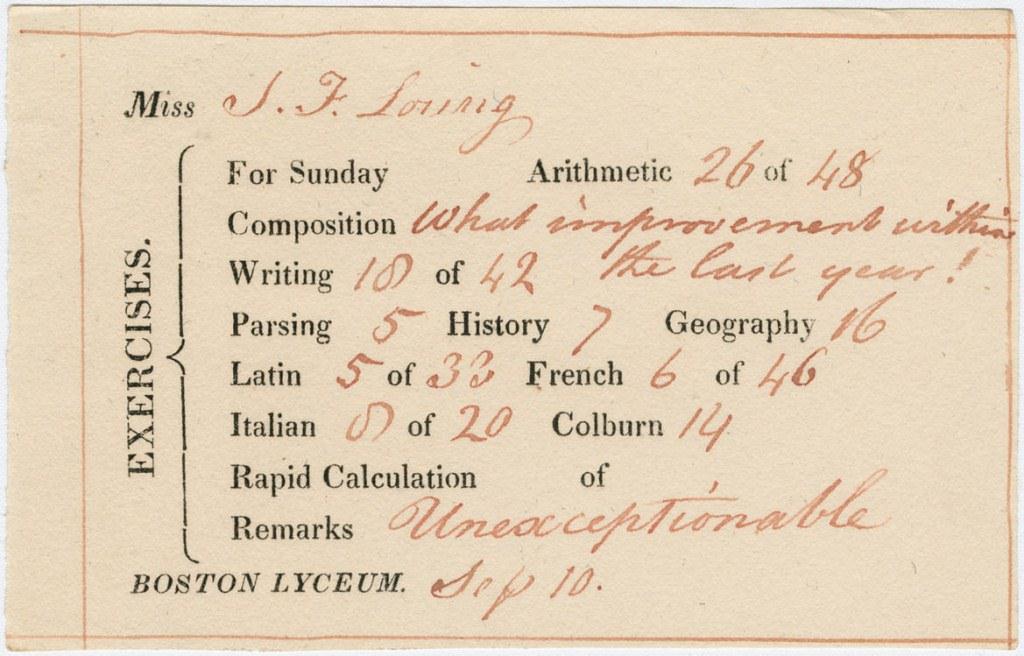

Another student (and another Sarah) who attended the school just before Miss Bryant was Sarah Loring (1811-1892). The MHS holds several of her report cards, ca. 1824-1827. Although she earned a few medals for good composition and good improvement, as well as one Eye of Intelligence award, she ranked lower in the class, and Dr. Park’s remarks were more mixed. On the plus side, she was “full of zeal,” “faithful,” “amiable, studious,” “attentive,” and “indefatigable.” However, she displayed an exasperating lack of discipline. She talked too much (“If I did not hear Miss Loring’s voice so often, she should have great praise.”), arrived late (“Exercises begin at 8.”), and disrupted lessons (“Still interrupts me sometimes.”). She was often marked for disturbance, and one card includes the ominous warning: “Beware of another week.”

But no matter how difficult the pupil, Dr. Park almost always mitigated his criticism with encouragement. He frequently assured Sarah that she wrote well, even though he was disappointed by her “dreadful” handwriting: “Your Composition has improved much; you want more care in the execution.” He also complained that her essays were too short: “You write well. Do write longer.” But what Miss Loring needed most, he thought, was confidence. When she wasn’t intimidated by her lessons, she showed great skill. For example, he described her Latin work as “excellent. Was afraid of Horace, but acquits herself well.” And after one impressive composition, he praised her for making “scarcely an error. Courage give the same freedom to your mind, when you take your pen, that it has at other times, & you will find no difficulty.”

Even earlier papers related to the Lyceum are located in the Rogers-Mason-Cabot family papers. This collection includes a book of essays written by Hannah Rogers (1806-1871) when she was a student of Dr. Park’s between 1822 and 1824. Subjects include friendship, education, religion, etc., and many of the essays won gold medals and medals for literary ambition and rapid improvement. Dr. Park carefully corrected Hannah’s grammatical errors, but added other comments that reveal his affection for and pride in his student. In spite of “small inaccuracies,” he wrote, Hannah’s “powers are vigorous, and your style very much to my taste. With a very little more practice, you will rank among my best in composition.” And her essay about happiness and misery provoked this thoughtful response:

Though there are some small errors in the execution, (particularly the want of periods, where the sentence is completely ended) this is one of the ablest exercises you have produced. Though a sombre view of mankind, it contains strong and just observations, which show a discriminating and reflecting mind.

The Boston Lyceum for the Education of Young Ladies was open for 20 years. One of its most prominent students was Margaret Fuller, who attended from 1821 to 1822. For more information on Fuller’s studies and the school, see Charles Capper’s 1992 biography or Megan Marshall’s Pulitzer Prize winning biography, published in 2013.

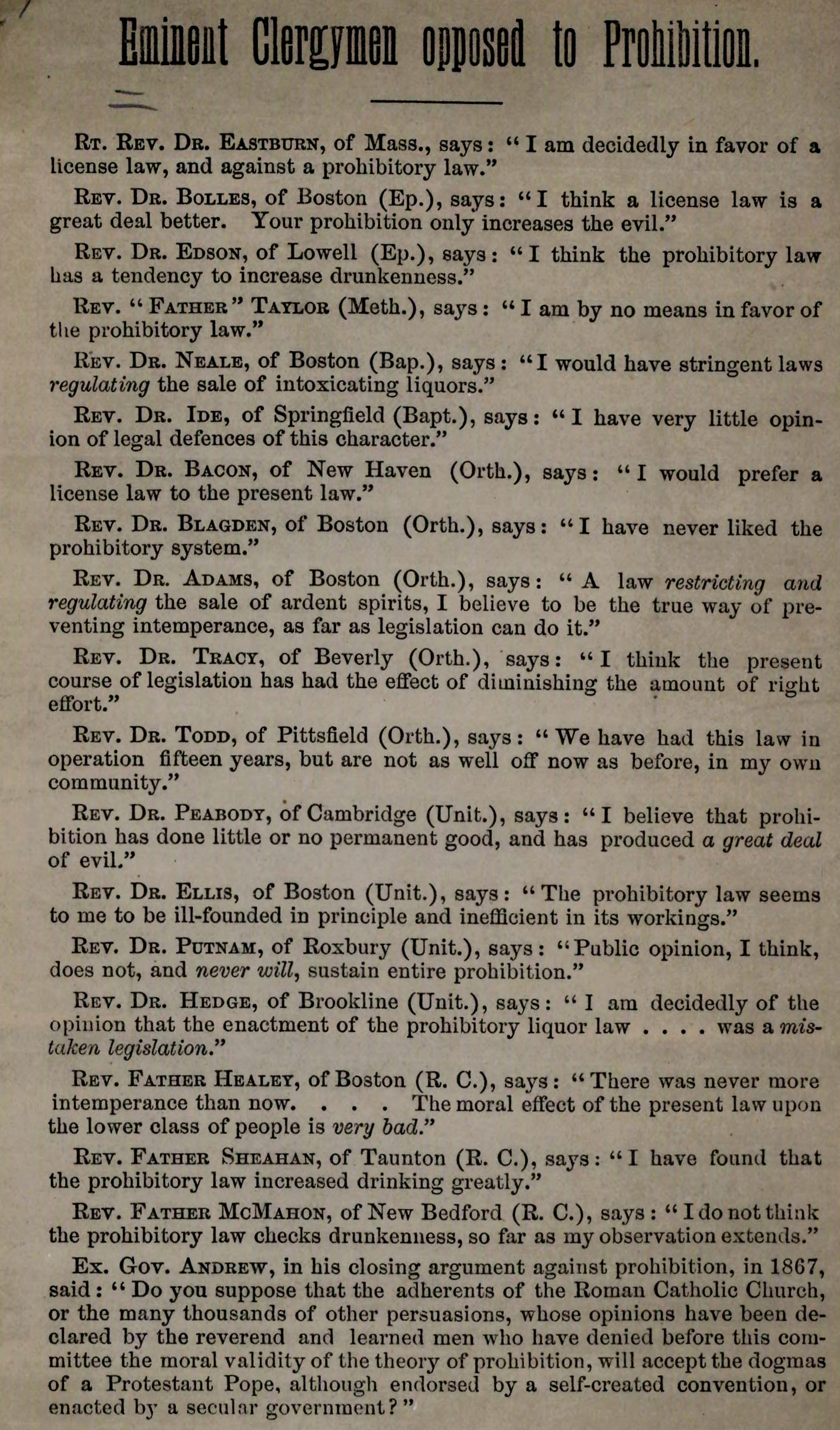

On November 10, students from Needham High School returned to the MHS for a program on the coming of the American Revolution in Boston. They analyzed propaganda from the 1760s and the 1770s, including this entertaining newspaper article encouraging colonists to

On November 10, students from Needham High School returned to the MHS for a program on the coming of the American Revolution in Boston. They analyzed propaganda from the 1760s and the 1770s, including this entertaining newspaper article encouraging colonists to  and the African Americans in the Civil War in order to help select topics for an upcoming project. Students then discussed the messages promoted in abolitionist propaganda such as

and the African Americans in the Civil War in order to help select topics for an upcoming project. Students then discussed the messages promoted in abolitionist propaganda such as