By Amanda A. Mathews, Adams Papers

On October 3, 1789, President George Washington issued a proclamation, calling for November 26 of that year to be celebrated as a day of thanksgiving by the whole nation now independent and united under a new Constitution. Exactly 74 years later, President Abraham Lincoln, seeing the nation embroiled in a bitter, devastating, and deadly Civil War, recognized that there was still much to be grateful for as “the Most High God, who, while dealing with us in anger for our sins, hath nevertheless remembered mercy. It has seemed to me fit and proper that they should be solemnly, reverently and gratefully acknowledged as with one heart and one voice by the whole American People. I do therefore invite my fellow citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens.”

Charles Francis Adams was one of those Americans sojourning in foreign lands as the United States minister to Great Britain. Invited by a group of Americans living in London to attend a Thanksgiving Day celebration and give a toast to President Lincoln, the dinner opened with a reading of Lincoln’s proclamation. No devotee of the president, Adams noted that the proclamation was “very good, and…therefore never emanated from Mr Lincoln’s pen.” In his diary, Adams summarized his toast and feelings on the honoree:

“The press here had sneered at the notion of a thanksgiving in the midst of a desolating civil war. I thought it a good opportunity, whilst avoiding the topic of victories over our fellow countrymen which necessarily take a shade of sadness, to explain more exclusively the causes of rejoicing we had in the restoration of a healthy national solidity in the government since the announcement of the President’s term. I went over each particular in turn. The result is to give much credit to Mr Lincoln as an organizing mind, perhaps more than individually he may deserve. But with us the President as the responsible head takes the whole credit of successful efforts. It certainly looks now as if he would close his term with the honor of having raised up and confirmed the government, which at his accession had been shaken all to pieces. And this a raw, inexperienced hand has done in the face of difficulties that might well appall the most practised statesman! What a curious thing is History! The real men in this struggle have been Messr [William] Seward and [Salmon] Chase. Yet the will of the President has not been without its effect even though not always judiciously exerted.”

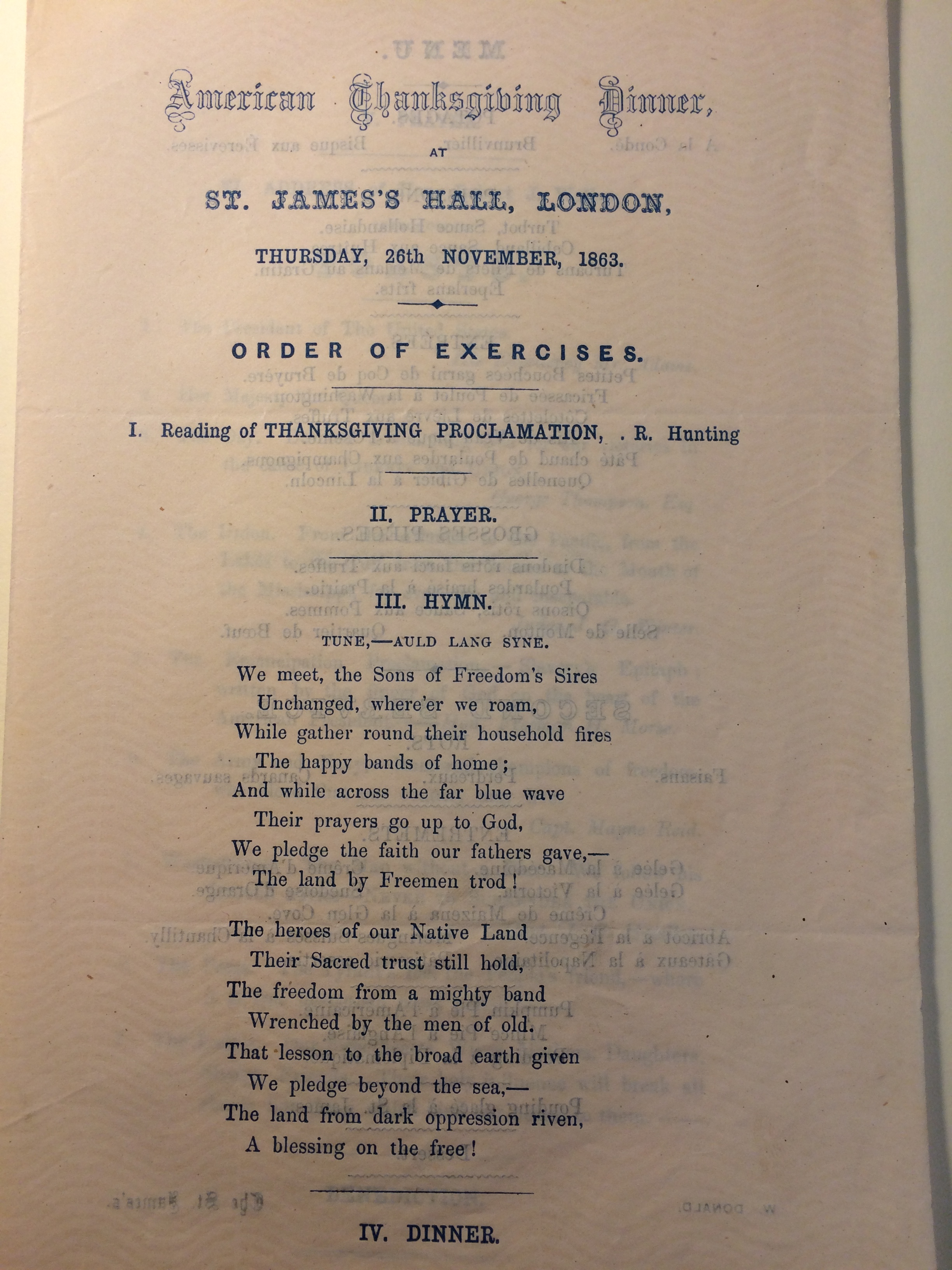

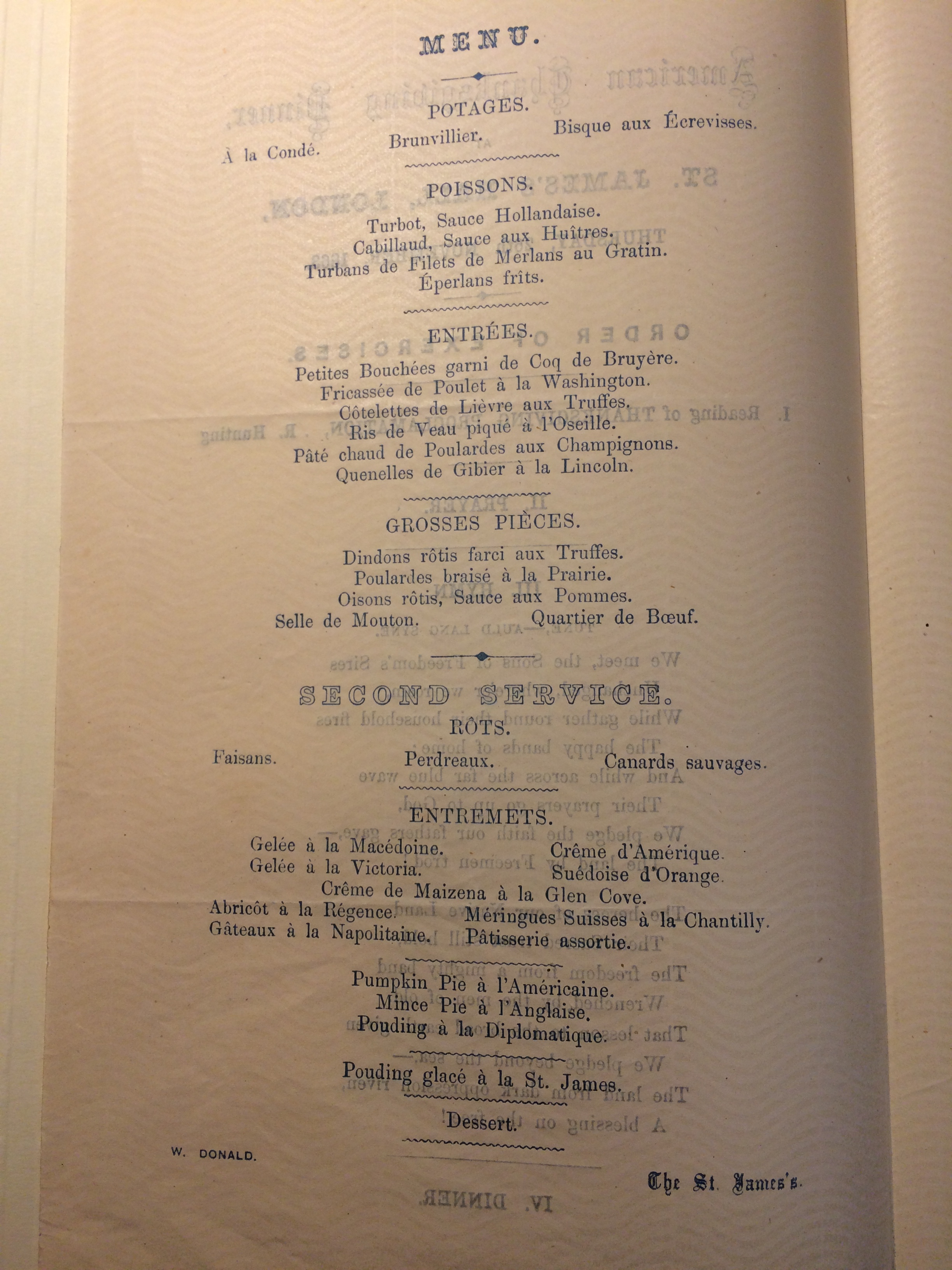

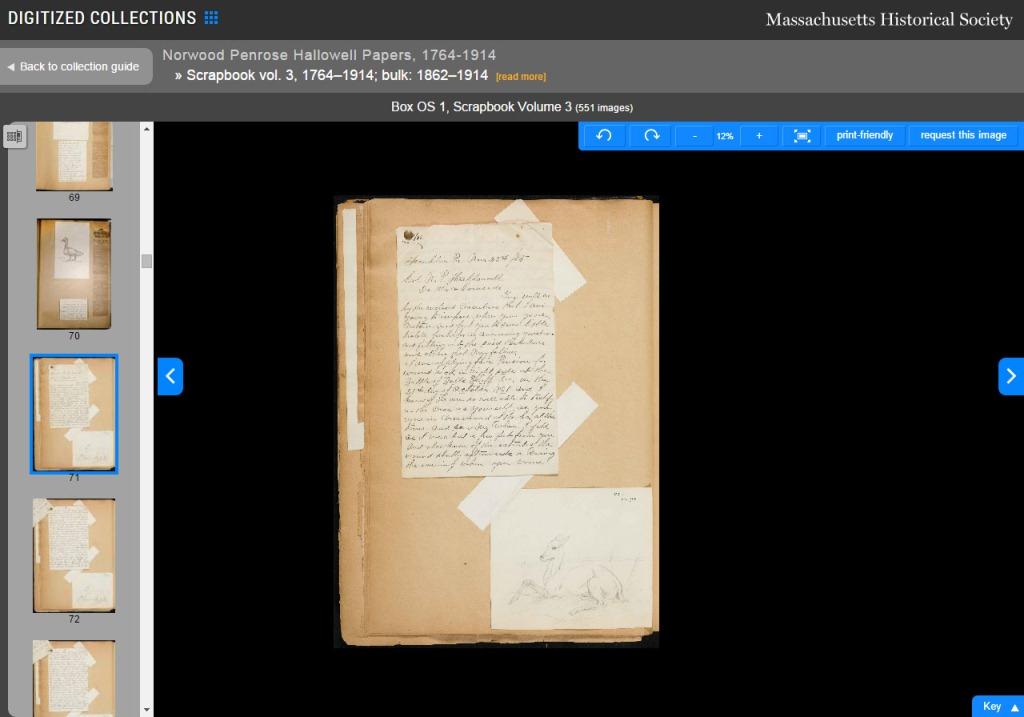

Shown here is the program for that Thanksgiving Day celebration. Since 1863, Americans around the world have stopped in late November each year for a day of joy and thanksgiving with friends and family, as we will tomorrow. Wishing you and yours a Happy Thanksgiving!