By Daniel Hinchen, Reader Services

John Boyle O’Reilly’s faults were few, his virtues many. He did his work fearlessly and brilliantly. He did it, too, with a conspicuous ability which was seen and appreciated by men of all classes and men of all creeds. He has gone from among us, but he has left a record which the land of his nativity, his adopted country, and the city in which he lived will always cherish with pride, with honor, and with respect. –Col. Charles H. Taylor (Memorial of John Boyle O’Reilly from the City of Boston, Boston: By Order of Board of Aldermen, 1891)

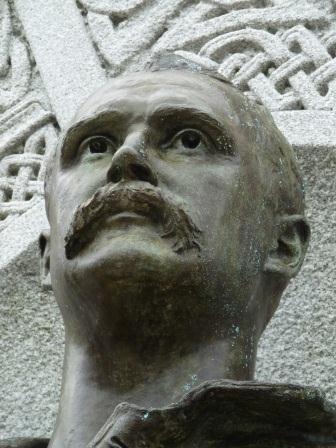

Across the street from the MHS, and facing back at it, is a large bronze bust commemorating John Boyle O’Reilly, an Irish-born poet, newspaperman, author,  and social activist who brought his passion and patriotism to Boston. He was a giant in the city and won the admiration and respect of all those he met. Upon his death in 1890, thousands of people descended on Tremont Temple to pay their respects.

and social activist who brought his passion and patriotism to Boston. He was a giant in the city and won the admiration and respect of all those he met. Upon his death in 1890, thousands of people descended on Tremont Temple to pay their respects.

The memorial that stands directly across from the MHS was designed by Daniel Chester French and erected in 1896. French was responsible for creating such iconic sculptures as The Minute Man statue standing in Concord, MA, a statue of a seated John Harvard that is in Harvard Yard, and the giant sculpture of Abraham Lincoln that occupies the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.

French’s monument to John Boyle O’Reilly features a large bronze bust of O’Reilly on one side. On the reverse is a sculpture of Erin (representing Ireland), who is weaving a wreath and is flanked by her two sons, Poetry and Patriotism.  The figures are placed in front of a backdrop composed of a Celtic cross and Celtic knots carved into the stone.

The figures are placed in front of a backdrop composed of a Celtic cross and Celtic knots carved into the stone.

While there is no known large body of O’Reilly’s personal papers, the MHS holds letters written by O’Reilly scattered through our collection, including material in the Frederic Jesup Stimson Papers, the DeGrasse-Howard Papers, and the William Eustis Russell Papers. The MHS also hold a number of published items authored by O’Reilly, including his novel Moondyne: A Story from the Under-world (1879), and transcriptions of several speeches he made in his lifetime. The Boston Public Library newspaper room provides access to the full run of the Boston archdiocesan newspaper Pilot, including the issues produced during O’Reilly’s tenure as editor. To learn more about the life, death, and times of John Boyle O’Reilly, visit the MHS library to discover additional source materials.

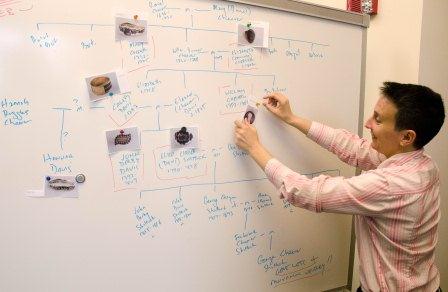

We are working on a book to coincide with the Society’s upcoming exhibition on mourning jewelry. The book, titled In Death Lamented: The Tradition of Anglo-American Mourning Jewelry, features mourning jewels from the Society’s collection and from the private collection of the author, Sarah Nehama.

We are working on a book to coincide with the Society’s upcoming exhibition on mourning jewelry. The book, titled In Death Lamented: The Tradition of Anglo-American Mourning Jewelry, features mourning jewels from the Society’s collection and from the private collection of the author, Sarah Nehama. Just think of the variously colored steeples that dot the campus of Harvard in nearby Cambridge; the golden dome of the State House; and of course, the grand brownstones that line Newbury and Beacon Streets and Commonwealth Avenue. One architectural style that is not well represented in Boston, though, is the Tudor Revival style. And yet, just around the corner from the MHS, among the rows of stone and brick apartment buildings, is a fine example of that style.

Just think of the variously colored steeples that dot the campus of Harvard in nearby Cambridge; the golden dome of the State House; and of course, the grand brownstones that line Newbury and Beacon Streets and Commonwealth Avenue. One architectural style that is not well represented in Boston, though, is the Tudor Revival style. And yet, just around the corner from the MHS, among the rows of stone and brick apartment buildings, is a fine example of that style. A quick look at the building’s exterior shows one repeated feature that hints to its original use: around the building are several large portals — some arched — resembling modern-day garage doors giving the viewer the impression of stables.

A quick look at the building’s exterior shows one repeated feature that hints to its original use: around the building are several large portals — some arched — resembling modern-day garage doors giving the viewer the impression of stables.  Marian Hooper Adams was nicknamed “Clover” by her mother, who felt that her daughter’s birth was a lucky occurrence. Born into a wealthy, prominent Boston family, Clover was raised in privilege and highly educated. Her mother died when she was five, but Clover remained very close to her father for the rest of her life. In 1872, at the age of 28, she married the historian Henry Adams, who was teaching at Harvard. After five years they moved to Washington, DC, residing near the White House, and began hosting an exclusive salon of politicians, writers, and thinkers. Despite this stimulation, Clover and Henry were bored, and the spark went out of their marriage. Their problems intensified due to the fact that they were unable to have children.

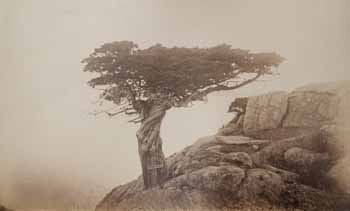

Marian Hooper Adams was nicknamed “Clover” by her mother, who felt that her daughter’s birth was a lucky occurrence. Born into a wealthy, prominent Boston family, Clover was raised in privilege and highly educated. Her mother died when she was five, but Clover remained very close to her father for the rest of her life. In 1872, at the age of 28, she married the historian Henry Adams, who was teaching at Harvard. After five years they moved to Washington, DC, residing near the White House, and began hosting an exclusive salon of politicians, writers, and thinkers. Despite this stimulation, Clover and Henry were bored, and the spark went out of their marriage. Their problems intensified due to the fact that they were unable to have children. Clover had always been interested in art and she found an outlet for her frustrations in a new camera in 1883. She learned the painstaking development process and began to take photographs of people, landscapes, and animals (she was a great lover of dogs and horses). Although a few of her photographs show traces of humor, including those of her dogs posed at a table set for tea, many of Clover’s photographs convey the melancholy and isolation of her own experience.

Clover had always been interested in art and she found an outlet for her frustrations in a new camera in 1883. She learned the painstaking development process and began to take photographs of people, landscapes, and animals (she was a great lover of dogs and horses). Although a few of her photographs show traces of humor, including those of her dogs posed at a table set for tea, many of Clover’s photographs convey the melancholy and isolation of her own experience.