By Dan Hinchen,

Over the last couple of weeks, we in Massachusetts were reminded of the unpredictability and harshness of the winter in New England. Of course, we are not alone and a significant portion of the rest of the country received an even greater shock. Still, the driving snow, sub-zero temperatures, and bitter winds force us to remember what a coastal winter can be. But if you think your commute was bad, the experience of Roger Williams might make you turn up the heat and clutch your hot chocolate a bit more tightly.

In October of 1635, after various hearings and disputes over intersecting matters of theology and secular power, Massachusetts Bay banished Roger Williams forcing him to leave the colony’s borders. But with winter coming on and Williams falling ill the court allowed him the courtesy of commuting the sentence until spring on the condition that Williams would not speak publicly in the interim. He consented to this term and agreed not to publicly proclaim his views.

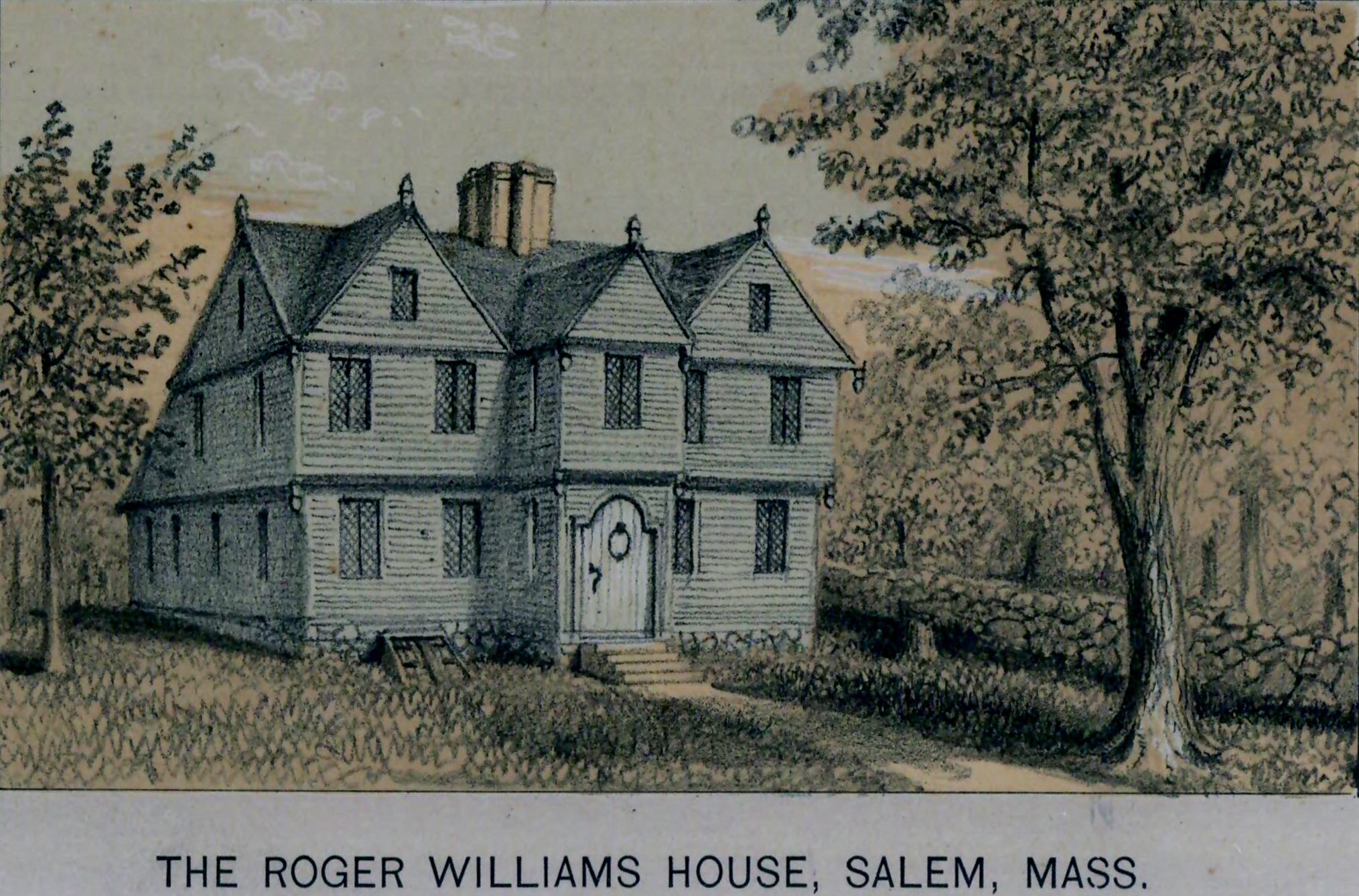

This agreement did not prevent Williams from welcoming his friends and followers into his home and holding private discussions. However, the Massachusetts court viewed even this as a breach of his promise and, in January, 1636, sent armed soldiers led by Captain John Underhill to Williams’ home in Salem to arrest him and put him on a ship bound for England.

As a blizzard and accompanying gale blustered out of the northeast, the ailing Williams received a secret message from none other than Governor John Winthrop, alerting him to the approaching soldiers. By the time Underhill and his men arrived, Williams had been gone three days.

Williams escaped with his life, liberty, and little else. Leaving his wife and children behind until he could find a new home, he plunged into the winter woods by himself. “He entered the wilderness ill and alone…Winthrop described that winter as ‘a very bad season.’ The cold was intense, violent; it made all about him crisp and brittle…The cold froze even Narragansett Bay, an extraordinary event, for it is a large ocean bay riven by currents and tidal flows.”i

“But the cold may also have saved his life: it made the snow a light powder . . . it lacked the killing weight of heavy moisture-laden snow. The snow also froze rivers and streams which he would otherwise have had to ford.”ii A silver lining to the winter clouds is one that we benefited from during our last storm and surely made our shoveling much easier.

That Roger Williams endured his trek from Salem to Narragansett Bay is no doubt a testament to his personal relationships with the native peoples and their willingness to give him shelter. Yet, “There was no comfort in this shelter. For fourteen weeks he did ‘not know what Bread or Bed did meane.'”iii

And yet Roger Williams survived this ordeal and soon thrived in his new home of Providence, itself a further attestation to the good relations that Williams shared with the indigenous tribes. While Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies both were formed by English settlers putting roots down in a spot without much thought for the original inhabitants, Williams was able to secure a piece of land with the blessing of the Narragansett sachem Canonicus and his nephew Miantonomi, two men who were otherwise ill-disposed toward the English.

“Canonicus and Miantonomi gave Williams permission to settle there after negotiating what seemed clear boundaries. Williams later declared that Canonicus ‘was not I say to be stirred with money to sell his land to let in Foreigners. Tis true he recd presents and Gratuities many of me: but it was not thouhsands nor ten thouhsands of mony could have bought of him and English Entrance into this Bay.’ He said the land was ‘purchasd by Love.'”iv

Though we grumbled about the cold and snow that we experienced last week, chances are the memories are already fading. Williams’ journey, though, had a lasting effect: “Thirty-five years later he would refer to that ‘Winter snow wch I feele yet.'”

To find out more about the life of Roger Williams, try these biographies:

-

- – Barry, John M., Roger Williams and the Creation of the American Soul: Chuch, State, and the Birth of Liberty (New York: Viking Penguin, 2012).

– Gaustad, Edwin S., Roger Williams (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005).

– Winslow, Ola Elizabeth, Master Roger Williams: a biography (New York: Macmillan, 1957).

Also, visit our online catalog, ABIGAIL, and search for Williams, Roger as an author to see what works the MHS holds written by Williams or where he appears in other manuscript collections.

iBarry, John M., Roger Williams and the Creation of the American Soul: Church, state, and the Birth of Liberty (New York: Viking Penguin, 2012) 213.

iiBarry, Roger Williams and the Creation of the American Soul, 213.

iiiBarry, Roger Williams and the Creation of the American Soul, 214.

ivBarry, Roger Williams and the Creation of the American Soul, 217.

This photograph of a fellow worker illustrates the hectic pace of Hall’s canteen work.

This photograph of a fellow worker illustrates the hectic pace of Hall’s canteen work. “Intersection of Boylston Street and Charlesgate from the West. Photograph by Anna J. Clutterbuck-Cook, January 2014.”

“Intersection of Boylston Street and Charlesgate from the West. Photograph by Anna J. Clutterbuck-Cook, January 2014.” “Charlesgate Park. Photograph by unknown photographer, circa 1893-1896. Sarah Gooll Putnam Diaries, vol 20, MHS.”

“Charlesgate Park. Photograph by unknown photographer, circa 1893-1896. Sarah Gooll Putnam Diaries, vol 20, MHS.” “Charlesgate Park from the corner of Boylston Street and Charlesgate East. Photograph by Anna J. Clutterbuck-Cook, January 2014.”

“Charlesgate Park from the corner of Boylston Street and Charlesgate East. Photograph by Anna J. Clutterbuck-Cook, January 2014.”