By Gwen Fries, Adams Papers

Every time I write a blog post or teach a workshop and mention John Adams’s complicated relationship with Benjamin Franklin or mistrust of Alexander Hamilton, some member of the public will invariably scoff, “Who did John Adams like?”

I’m always taken aback by this attitude. “He liked lots of people!” I protest. In fact, the word that jumps to mind when I think of John Adams is “gregarious.” Adams loved to tell stories, crack jokes, and debate the topics of the day. He preferred his house bursting at the seams with children, grandchildren, and friends. Adams was a member of various dinner clubs and societies and well into old age welcomed curious citizens into his home for a friendly chat.

So how have we collectively developed an image of a scowling, curmudgeonly John Adams with a strong dislike of everyone besides Abigail? Probably because for many of us—myself included—our first introduction to John Adams was through a screaming Paul Giamatti in HBO’s John Adams or a sniping William Daniels in 1776. (And his reputation surely hasn’t been helped by the demonic “Welcome, folks, to the Adams Administration” voiceover in Hamilton that makes audience members feel they’ve left the sunshine days of President Washington behind and are advancing through the open gates of Hell.)

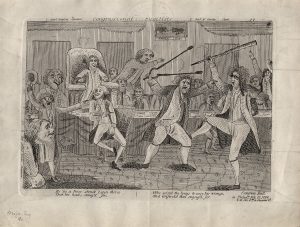

Adams undeniably spewed enough venom to inspire scriptwriters to cast him as the exasperated, irritated comic relief—the late Bob Dole called him the “eighteenth-century Don Rickles.” But imagine if the memory of you that is passed down to posterity consisted only of the words you used while venting to a trusted friend after a particularly stressful day (or even what you wrote in your diary). Adams is often remarkably generous in his descriptions of his contemporaries, so why are we only familiar with the insults? It may be because Adams’s gripes are funny, snappy, and eminently quotable. Posterity likely wouldn’t remember a lengthy diatribe against Pennsylvania’s John Dickinson, but we can forever associate him with his two-word title, the “piddling Genius.”(See also: Hamilton as the “bastard brat of a Scotch Pedler,” etc., etc.)

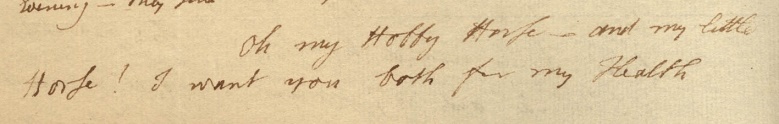

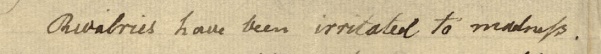

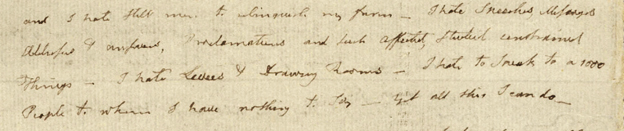

Another reason we tend to view John Adams as unsociable is that the people he liked best aren’t preserved in the pantheon of American political history. Adams cared for two things: his family’s peace and happiness and his country’s peace and happiness. He had, in effect, sacrificed the former for the latter, and thus jealously guarded the latter. Where we see serene and omniscient statesmen, Adams saw self-absorbed, blundering politicians undermining his life’s work. (I think most of us agree that a mistrust of politicians is probably wise. In his line of work, it’s remarkable Adams found so many people he did like.) While serving as Vice President, John wrote home to Abigail: “I hate Speeches, Messages Addresses & answers, Proclamations and such Affected, studied constrained Things— I hate Levees & Drawing Rooms— I hate to Speak to a 1000 People to whom I have nothing to Say.”

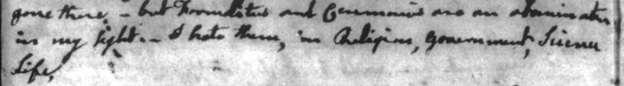

Adams’s idea of contentment was sitting at his fireside after a long day’s work on his farm, surrounded by family and lifelong friends, speaking freely. “Formalities and Ceremonies are an abomination in my sight. —I hate them,” a 34-year-old John Adams confided to his diary. He was not to change his mind. Though he did acquire true friends during his political career—Benjamin Rush comes to mind—most of Adams’s nearest and dearest were Quincy farmers, in-laws, and former law students.

If John Adams were half the curmudgeon he’s made out to be, I wouldn’t delight in sitting down each day to read his letters. But he’s kind and affectionate, witty and wise, candid, (sometimes exasperating), generous, and supremely lovable. And so, I delight.

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding is provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, and the Packard Humanities Institute. The Florence Gould Foundation and a number of private donors also contribute critical support. All Adams Papers volumes are published by Harvard University Press.

![Abigail Adams Smith, miniature portrait on porcelain tile by an unidentified artist, [18--]](http://www.masshist.org/beehiveblog/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Abigail-Adams-Smith-251x300.jpg)