By Susan Martin, Collection Services

Those of us who process manuscript collections are always stumbling on interesting and unexpected finds. I was recently working with the MHS’s George E. Ellis papers to improve the arrangement and description of the collection, and one letter immediately caught my eye. It was written by 10-year-old Helen Keller.

Between 1888 and 1892, Keller was a student at Perkins School for the Blind in South Boston. (The school moved to Watertown, Mass. in 1912.) She found a happy home at Perkins, which she described in her 1902 autobiography The Story of My Life: “Until then I had been like a foreigner speaking through an interpreter. In the school where Laura Bridgman was taught I was in my own country.”

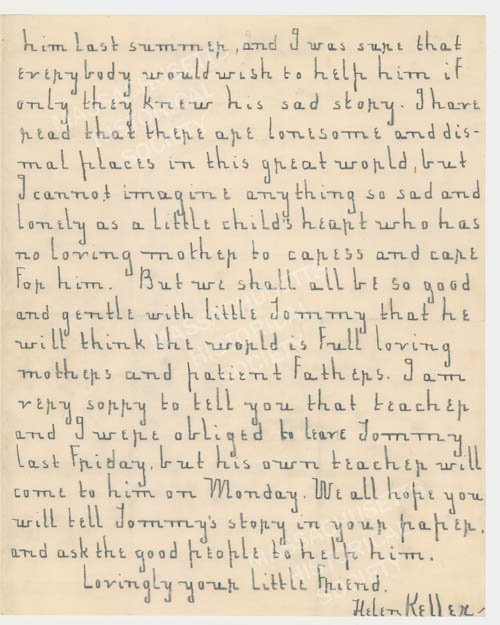

The subject of this letter, written to Dr. Ellis on 27 April 1891, is four-year-old Tommy Stringer, another Perkins student who was both blind and deaf. Stringer’s family was unable to support him, so he had been brought up from an almshouse in Pennsylvania to the Perkins kindergarten. Keller became his energetic advocate and wrote to friends and strangers alike, as well as newspapers, to solicit donations for his education. Ellis was one of the many who contributed. Keller wrote to him gratefully:

Mr [Phillips] Brooks once told me that love was the most beautiful thing in the world, and now I am sure it is, for nothing but love could brighten Tommy’s whole life. I think we ought to love those who are weak and helpless even more tenderly than we do others who are strong and beautiful….I have read that there are lonesome and dismal places in this great world, but I cannot imagine anything so sad and lonely as a little child’s heart who has no loving mother to caress and care for him. But we shall all be so good and gentle with little Tommy that he will think the world is full [of] loving mothers and patient fathers.

It just so happens that Ellis was the president of our very own MHS at the time, an historian, and a former minister of the Harvard Church in Charlestown, Mass. He corresponded with many notable people, but this letter, written in large, neat, blocky handwriting, stands out from the rest. It’s amazing to realize that it was written just four years after Keller met Annie Sullivan, at which time Keller could barely communicate at all, let alone read and write. (About a year later, she explained to the readers of the children’s magazine St. Nicholas how she wrote by placing a “grooved board” between the pages, probably some version of a noctograph.)

George E. Ellis died in 1894. In his will, he bequeathed $30,000, as well as his home and all its contents, to the MHS. Funds from the sale of his property were used to help build and relocate to our current home at 1154 Boylston Street. Our very own research room, Ellis Hall, is named after him. We hope to see you there sometime!

Thomas Stringer graduated from Perkins in 1913 and became a woodworker in Pennsylvania, dying in 1945.